THE ELECTION TO appoint the 15th president of India has once again put the spotlight on the Rashtrapati Bhavan. Raisina Hill is the largest office-cum-residence of any head of state in the world. And if the grandeur of an office is usually emblematic of the power and influence of the occupier of the building, the president of India is an exception.

When the constituent assembly debated the institution of the president, there were several opposing views on the selection process to be adopted, and the powers the head of state should have. Finally, it was decided to combine in the Indian president some features of the US president and the monarch of England. Unlike the monarch with whom the Indian president is often compared with, the election of the Indian president gives the office its democratic character and permanency, while the monarch of England has to innovate to stay relevant.

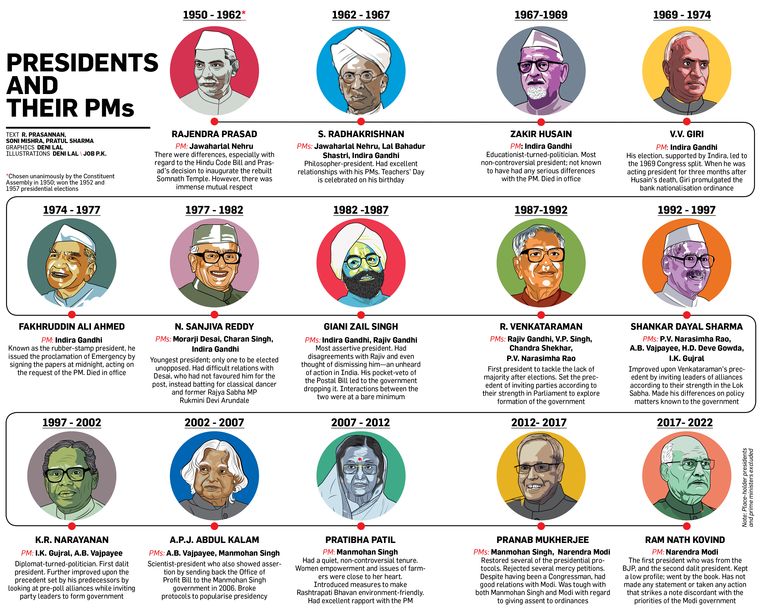

As India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru said, the Indian president is a “head that neither reigns nor governs”. But, that may be an extreme view and obfuscates the influence the president wields and the critical power he could be called upon to exercise. This is despite the 42nd amendment (1976) that makes it obligatory for him to act on the advice of the council of ministers.

Notwithstanding his largely ceremonial roles, the president of India, before the amendment and thereafter, has played a significant role in Indian polity. He has enriched its democratic values by playing the role of a guardian and a catalyst, though he may be vested with no real powers. Yet, he is a symbol that people look up to and the last stop for the opposition to air its grievances, especially against a government that may have an overwhelming majority.

The president is also the powerful aggregator of people’s grievances, a figurehead who puts his weight behind social issues on which immediate government attention has to be rivetted. The president summoning the concerned minister-in-charge and expressing his grievance is enough to awaken the government to urgent remedial action. The best example is perhaps of the shameful Nirbhaya rape case where the president, after hearing several viewpoints, communicated to the prime minister and home minister his anguish at what had happened and the need for the government to take urgent action to ensure the protection and dignity of women.

The amendment also did not make the president a rubber stamp. He can still exercise the pocket veto, which means that he can just keep the bill and take no action on it. In 1986, former president Giani Zail Singh had prevented the Indian Post Office (Amendment) Bill, which gave the government sweeping powers to intercept communication, from becoming a law. What sets apart the Indian president from the other elected, non-elected and appointed authorities in India is that a specific duty has been cast upon him to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution” and he is the only one who takes the oath of office swearing to do so. Embedded in the important four words—preserve, protect and defend—is a special duty cast to act as a sort of a gendarme, the last and ultimate gatekeeper and guardian of constitutionalism in the country. But has the president played this role in the country? The answer is both yes and no.

The ability of the president to perform his role impartially and in accordance with his oath could be influenced by the party affiliations that must have played a part in his or her elections, and his standing in the party.

It is true that when the president and the government of the day are from the same party, his effectiveness as an impartial defender of the Constitution may be seen as being circumscribed by previous party affiliations, though it may be more imagined than real. It has also been the latter in some cases, for instance, when former president Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed signed the proclamation of Emergency without demur.

But if the occupant of the office may have been a towering political leader like the first president, Rajendra Prasad, and the 13th occupant of the office, Pranab Mukherjee, he is less likely to suffer from the fetters of party affiliations. It is no secret that Prasad did not hesitate to disagree with Nehru, though he himself was a political heavyweight. Mukherjee was another president cast in that mould. Though he was a Congress veteran, he did not hesitate to disagree with the views of the party to which he had belonged. He made his displeasure known so strongly to the senior ministers that he had summoned, that the prime minister had to hastily withdraw the Representation of the People (Amendment and Validation) Ordinance, 2013. Though there may have been no legal impediment in approving the ordinance, the president was concerned about the possible dilution of ethical standards in elected representatives of the country if it were signed into law. In doing so, he may have introduced a new convention of the president upholding the spirit of genuine participative democracy where money power does not guarantee election victory, something that the Constitution does not explicitly enjoin him to do but an aspect that he read into as the protector of the Constitution.

Mukherjee’s action sprang from his view on the need to protect the federal character of the Indian polity. In 2014, he stepped in to remove Kamla Beniwal, who was former governor of Gujarat and later transferred to Mizoram, after she was involved in some activities inconsistent with the dignity of her office. The next year, he summoned a senior government minister and communicated that J.P. Rajkhowa, the governor of Arunachal Pradesh, had overstepped his powers in preponing the session of the state legislature. He informed the minister that he was prepared to suo motu communicate that the governor does not enjoy his pleasure anymore as he had interfered without authority in the matters of the assembly.

Also read

- How many cross-votes? The question that lingers as presidential poll results are counted

- Over 99% polling in Presidential polls; 100% voting by MLAs in 11 states and Puducherry

- Naveen Patnaik seeks support of Congress MLAs for Draupadi Murmu

- When India’s first woman president flew a Sukhoi

- BJP ticks all the right boxes by nominating Droupadi Murmu

Besides, Mukherjee has also cautioned governments, both privately and in writing, to work within the framework of the Constitution. For instance, he strongly advised governments not to resort to the ordinance as a routine to make laws, underscoring that it is only a power given by the Constitution to address emergent situations that may arise when Parliament is not in session.

Perhaps, the most important power that the president exercises is when he decides to invite the leader of the largest political party or coalition that may have won after a general election. When there is a hung Parliament, he could use his discretion to invite who he believes has the best chance to command a majority in the Lok Sabha and instruct him to prove his support on the floor of the lower house. Although there is no legal consensus on whether a president is bound by the advice of a prime minister who has lost the majority in Parliament, he may be justified in not complying with the request of such a head of government to dissolve Parliament and hold elections especially if the president feels that any other leader would be able to get the majority support.

Besides powers that directly emanate from the provisions of the Constitution, president has stepped in to make the executive take note and take action in areas falling within the remit of ministries. As the visitor of over 150 Central universities, the periodic conference he holds influences policies of the government. The conferences of the vice-chancellors that Mukherjee held had a telling impact on policy formulation. He took select vice-chancellors on visits to expose them to systems and sign collaborations.

A president’s role may be limited by and influenced by his previous political affiliations. But if the president is a veteran of the ruling party or from the opposition, he may be better equipped to play the role of the protector of the Constitution and create healthy conventions to address the nation’s socio-economic concerns.

Mathew was additional secretary to president Pranab Mukherjee.