If it was the Yellow Brick Road that led Dorothy to Emerald City and the Wizard of Oz, it is the sweet scent of crimson roses mixed with smoky incense that will lead you to Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya’s dargah (mausoleum). There, you will see the cold, black-flecked white floor dotted with masked devotees waiting for redemption early in the morning. In the corner of the courtyard, socially distanced behind a latticed wall, lies Jahanara Begum. Though not quite Helen of Troy, the face that launched a thousand ships, Begum was an Indian princess who commanded Surat, one of the busiest ports of the Mughal Empire.

“Jahanara was given the jagir (land grant) of Surat and she took a lot of interest [in it],” says Najaf Haider, a professor of medieval history at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Though the sea did not loom large on the Mughal horizon, each emperor did travel to see the sea at least once. Akbar adventurously boarded “fast-moving boat(s) and ordered an assembly of pleasure and enjoyment,” says author Ira Mukhoty in Akbar: The Great Mughal. He is also said to have enjoyed a round of drinks with the briny sea air.

But the royal jaunt apart, the revenue figures indicate that trade was lucrative. The sea did have an impact on the royal treasury. While 80 per cent of the revenue of the Mughal state came from agriculture, overseas trade, too, brought in taxes. The Mughals’ revenue from Surat, a prosperous town, was an estimated 07.5 lakh a year.

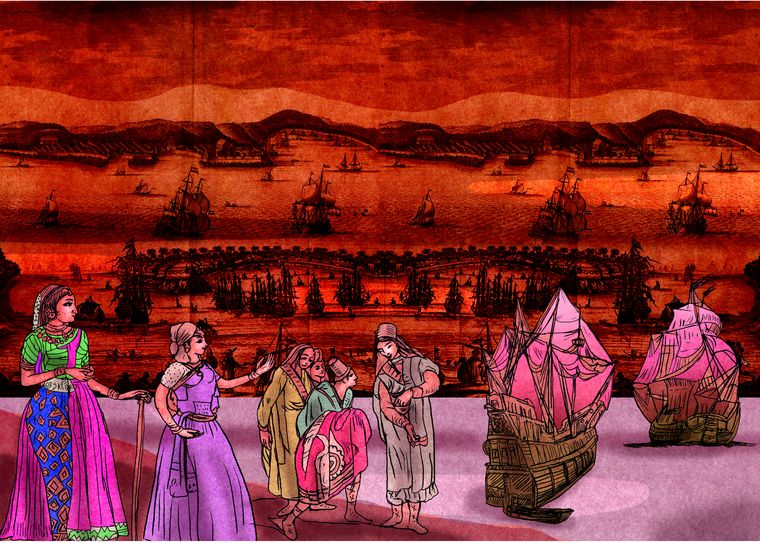

The seas also added to the wealth of the royal women, Jahanara being one of them. But, beyond receiving revenue from Surat, she also contributed to its prosperity. Sahibi, one of her ships, made its first voyage on October 29, 1643, to Mecca and Medina. According to author Shireen Moosvi, Jahanara ordered that “…every year fifty koni (about 150 pounds) of rice be sent by the ship for distribution among the destitute and needy of Mecca”. This was routine. The custodians of Mecca and Medina were often sent money—not bullion, but trade goods. More than just a trading port, Surat was also the gateway to Mecca.

Jahanara was not the only lady Mughal to embark on naval pursuits. Nur Jahan, one of Jahangir’s wives, also had ships; her choice of export was indigo and embroidered cloth. A shrewd businesswoman, Nur Jahan made deals with foreign traders such as the Portuguese.

But perhaps the pioneer of the ship trade in the harem was Maryam-uz-Zamani, Akbar’s wife. Author E.B. Findley describes her as “adventurous a trader’’ as no other. She had ships that travelled from Surat to the Red Sea, carrying cargo as well as ferrying passengers for hajj. Her primary investment was indigo. (There was an incident when an English agent, William Finch, outbid the cargo reserved for her. He was never heard from again).

The emperors, too, dabbled in the sea. For instance, the symmetry-obsessed Shah Jahan may be famous for his monument-sized heartbreak, but he had a competitive streak, too. “It was one moment when you saw a lot of activity,” says Haider. “The Mughal emperors, particularly Shah Jahan, built big ships to compete with the Europeans.” Many of these ships were built in timber-rich Gujarat. “We have interesting reports from the Dutch and the East India Company about these ships and how they were taking the lion’s share of the trade with the Middle East in the Indian Ocean, particularly in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea,” says Haider. “Until then, it was practically the monopoly of the European ships. These reports [show] us how hectic shipbuilding had become in the 1640-50s.”

But trade was not without danger, even for the nobility. The Portuguese, the Dutch and the English were fighting for monopoly. The Portuguese were particularly ruthless, even harassing hajj travellers. Once, Akbar, on his visit to Surat, had to get an assurance that pilgrims would be safe.

“The Mughal state took upon itself the responsibility of protecting its merchants to the extent that it could,” says Haider. There was a mechanism to settle disputes, set up arbitration tribunals and announce policy.

There was also piracy. And one of the greatest heists on the sea was carried out during Aurangzeb’s time. It was in 1695, and the ship was Aurangzeb’s Ganj-i-Sawai. It was filled with pilgrims, treasure and cargo and had its own escort, the Fateh Mohammad. Mastermind Henry Every teamed up with five other pirates—a grand alliance as it were—to attack the royal ship. About 500 pirates chased the Mughal fleet of 25 ships for five days, and opened fire to destroy the Ganj-i-Sawai’s mainmast.

It was a three-hour battle; plunder and rape followed. The pirates took 5,00,000 pieces of gold, silver, ivory and precious stones in what is believed to be one of the biggest such looting of the time. Every apparently escaped to the Bahamas, clearly the choice of absconders from time immemorial. (In another version, he goes to Ireland, but does not sell the diamonds as he is too afraid of being caught; there is a massive operation to try and nab him). Aurangzeb wanted revenge and threatened the English with all his might. He was later compensated. A version of this incident even finds itself in Daniel Defoe’s A General History of Pyrates.