A SOLDIER FELL into the ocean and was there so long that his nails fell off; a young groom left his wife of six weeks to fight in another continent; four prisoners of war escaped and were hidden by Italian villagers; a soldier came home to find his wife remarried. She thought he had died. These are some of the largely unremembered stories that I heard, of the 2.5 million Indians who fought in World War II, during my project to collect their stories and pictures.

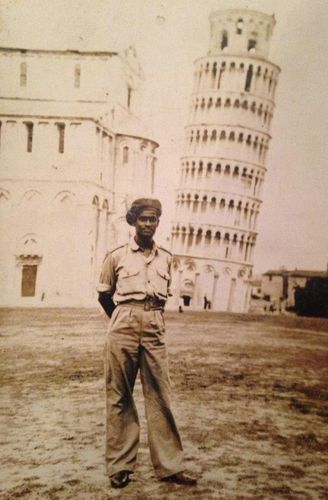

The project started on the opening day of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in December 2018, when a friend, Yamini Nayar, read that I was exhibiting an installation on Indian soldiers and the Battle of Monte Cassino of the Italian campaign of World War II. She sent me a photograph of her grandfather, Lt Col Goal Chakraborty, posing casually in front of the Leaning Tower of Pisa in his army uniform. The striking photograph gave me a visceral connection to those 2.5 million Indians.

This has led me down a rabbit hole of sorts. I recently completed six months in India on a Fulbright fellowship, crowdsourcing poignant images and stories of these unheralded people (mostly men) who fought for the British and by extension, the Allies. (I am still collecting images, so do send me more.) These photos and stories came from the north, south, east and west of India. They came from middle-class families, royalty and the poor. Some were swashbuckling young men who believed “in the cause”; others were looking for a regular salary. Once enlisted, all of them took their duties seriously.

I received one poignant story from Iona Sinha. Her grandfather Lt E.C. Joshua was one of the unremembered Indian soldiers. He contracted cholera on the Assam front in 1943 and was shipped back to Kirkee (now Khadki, in Maharashtra) where he died—12 days before her father was born.

Another is of Flight Lieutenant Arjan Jethanand Mirchandani. He had won a scholarship to pursue a PhD in England, and got stuck when the war started. He joined the signals unit of the Royal Indian Air Force and served in Europe, Africa and Burma. On his way to Burma, he passed through Hyderabad and Sindh, and was able to see his mother briefly. That same family was uprooted during the partition of India.

Mirchandani often sent photos and postcards of the murals that he made along the way. As Saaz Aggarwal writes in her book The Amils of Sindh, Mirchandani’s children say art was his way to shift his thoughts away from the atrocities and hardships of war. I have a photo of him on a camp bed in Burma and another of his sister dressed in his uniform!

I also have photos and stories from two prisoners of war, Lieutenant Ramachandra Salvi and Lieutenant General D.S. Kalha, whose families told stories of being sheltered and hidden by local Italian families in an extraordinary testament to our humanity.

During the process of collecting these, I have been fortunate to meet families of the soldiers and even a few veterans. As an artist, the viewers of my work have to connect with these soldiers to empathise with them. The universality of family photographs allows us to do that. Family snapshots create a sense of intimacy beyond the more formal imagery found in military archives. The family photographs that we all love reflect the personalities of these soldiers, allowing us a glimpse into their lives, their loves, their families and their personalities.

As with most of my projects, this archival material will go through an artistic intervention as it becomes a multimedia installation that spotlights this forgotten history. The installation will make the history accessible to a larger audience, and spark interest in the sacrifice of these soldiers.

The question sometimes asked is: “Were these soldiers serving on the wrong side of history?” Acknowledging their service will expand our understanding of the tapestry of who we are. Breaking free from our colonial past does not mean negating their experience. Instead, it can give us perspective. As Yasmin Khan wrote in The Raj at War, “Britain didn’t fight the Second World War, the British Empire did.”

If you have family photographs and stories, I would be happy to receive them on indiansoldiers1945@gmail.com.

The author is professor (art) at the University of Rhode Island.