LORD LINLITHGOW’S BIGGEST handicap, as Labour Party leader Clement Attlee remarked, was that he lacked “imaginative insight”. Jawaharlal Nehru thought of Linlithgow as a man “heavy of body and slow of mind, solid as a rock and with almost a rock’s lack of awareness”.

Unfortunately, Linlithgow happened to be the viceroy of India when World War II broke out. The man made things difficult for both the Indians and the British.

Though fighting the British for political freedom, most Indian leaders, except Subhas Bose, had been well disposed towards the British cause against Nazism. The Congress working committee had resolved not to make things difficult for Britain, in case of war.

Nehru had a record of anti-fascism that “far surpassed that of the British government”, writes Donny Gluckstein in A People’s History of the Second World War. While the British government of Neville Chamberlain was appeasing the fascists in the 1930s, Nehru toured Europe and declared support to the democratic elements fighting the fascists in Spain and Czechoslovakia. In Italy, he even refused an invitation to meet Benito Mussolini.

In short, Linlithgow only had to ask, and India would have supported the British cause in the war. In return, India wanted self-government, at par with the dominions of Canada and Australia. But Linlithgow had neither the imagination to ask India, nor the sagacity to advise London to promise self-government.

Instead, within hours of Britain declaring war on Germany, he proclaimed that India was at war. He did not consult the central legislature or the provincial governments that had been elected on the strength of the Government of India Act of 1935. He did not consult the Congress or the Muslim League. He did not consult any of the stakeholders in India’s political destiny.

When Linlithgow went on air, Nehru was on his way back from China, where he had declared support to Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist forces that were fighting the imperial Japanese for nearly half a decade. During his stopover in Rangoon, when the press asked him about Linlithgow’s proclamation, Nehru said: “This is not the time to bargain. We are against the rising imperialism of Germany, Italy and Japan and the decaying imperialisms of Europe.”

In India, Subhas Bose, who had just resigned as Congress president over his differences with Nehru and Sardar Patel, seized upon this. Proclaiming that “British adversity is India's opportunity”, he organised protests when Nehru landed in Calcutta. Sensing that a split was imminent within the national movement, Mahatma Gandhi declared that the Congress would finalise its stand only after Britain defined its war aims.

It was the memory of their bitter experience after World War I that made the Congress and the Muslim League hold back. They had wholeheartedly supported Britain in World War I, and had hoped that the British would move towards granting self-government after the war. But all that they got was the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh, and a diarchy through the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms. So now, when World War II broke out, they told Linlithgow: No more promises; give us self-government now and we will be there to defend the Commonwealth.

Linlithgow refused. The Congress governments in the provinces resigned in protest. Later, in February 1940, the viceroy told Gandhi that a new constitution would be drawn up after the war; but Gandhi was not impressed.

Linlithgow called Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who agreed to support the war effort if the British promised not to deal with the Congress behind his back. Linlithgow gave his word.

Gandhi, quick to sense the danger of a communal divide, persuaded the Congress to declare “nothing short of complete independence” as their demand and threatened civil disobedience. The political parting of ways between the British rulers and India’s leaders happened there.

Linlithgow had one more chance in August 1940. When they heard of the fall of France; of the desperate evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk; of the misery of the British people facing the daily Luftwaffe bombings; and of the fear of imminent invasion of Britain itself, Indian leaders’ hearts melted again. The Congress made another offer to cooperate if at least a provisional national government could be established in Delhi.

By now, the government of Chamberlain and the India-friendly Lord Halifax in London had given way to arch-imperialist Winston Churchill. On London’s instructions, Linlithgow replied with the most mulish ‘no’ ever said by a liberal regime to a friendly offer. Not only the Congress, but Jinnah’s Muslim League, too, was outraged. As the Congress threatened civil disobedience, Linlithgow threw most of its leaders into jail.

By March 1941, Bose had escaped house arrest and fled to Moscow. When the Russians spurned his pleas for help against the British, he went to Berlin. Soon he began radio appeals to Indians in Europe and elsewhere to support the Axis cause.

By now, big power equations were changing. Having signed a non-aggression pact, Germany and the Soviet Union had been dividing Europe into their spheres of influence. But in mid-1941, Hitler invaded the Soviet Union, suddenly turning his ally into an enemy. Britain thus got a powerful ally in Europe, and the British administration in India got the support of the Soviet-leaning communists in India.

The strategic perception from India, too, had changed. Since the 19th century, the biggest British concern in India was a possible expansion of the Tsarist and then the communist empire into India’s northwest. Thus most of the Indian army and air defence installations had been stationed in the northwest when the war broke out. Now, with the Soviet Union having become an ally, there was no more concern about India’s northwest. This enabled the viceroy to withdraw Indian troops from the northwest and send them to the Middle East and North Africa to secure British interests.

But, soon a new enemy appeared on the eastern horizon and he was coveting India.

On December 8, 1941, Japan not only bombed America’s Pearl Harbour, drawing a new power into the war, but also invaded British Malaya and Singapore, all of which were garrisoned by mostly the Indian Army. In two days, the Japanese sank two British warships in the South China Sea and, on December 11, invaded Burma. The war was now coming close to home for India. A panic-stricken Linlithgow freed the national leaders and expanded the executive council, but was still unwilling to make any political offer.

The biggest shock of the war in the east came on February 15, 1942. That day, Fortress Singapore, considered the eastern gate of the British empire as also India’s strategic perimeter, fell to the Japanese. An exasperated Churchill described it as “the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history”.

Within days, the Japanese bombed Chittagong and other ports in the Bay of Bengal. By now, the Americans, too, were putting pressure on Churchill to consider India’s demands more favourably. As Rangoon fell, it was clear that Calcutta would not be far behind. Alarmed, Churchill offered to send his cabinet colleague Sir Stafford Cripps to negotiate with Indian leaders.

Cripps was chosen for his three qualities. One, he had leftist leanings and thus could jell well with Nehru and others. Two, he had a sympathy for the Indian cause. Three, he could sup with the vegetarian ‘devils’. Like Gandhi, he was a sworn vegetarian.

But Cripps could not make much headway because his mandate was limited. The most he could offer was a constitutional assembly and dominion status, both of which would come after the war. Gandhi dismissed the offer as “an undated cheque on a crashing bank”.

It was not just rhetoric. Gandhi and the Congress, though sympathetic to the British cause, were convinced that Britain was crashing. They were worried about the security of India in the event of a British defeat. With the fall of Rangoon, they were convinced that the British would be defeated at the gates of India, and be forced to leave India, leaving a vacuum which the Japanese would occupy.

They did not want that to happen. Instead, as the journalist Durga Das observed, they wanted an Indian government to be in place in Delhi, with the Indian army commanded by an Indian, to fight the Japanese even after the British were forced to leave. Interestingly, even Archibald Wavell, who was then commander-in-chief of India (he would later become viceroy), was favourable to the idea. But Churchill simply refused, leaving Cripps helpless.

Yet, the Indian leaders were willing to help. The Congress passed another resolution on July 14, 1942, offering that once given self-government, they would not only commit India to the Allied war effort against Japan, but also allow British and other Allied armies to be stationed in India, along with Indian troops, to fight the Japanese. But Churchill did not even acknowledge the offer.

Disgusted and desperate, the Congress authorised Gandhi to decide the next course of action. He did it with the strongest two words that he ever uttered in his political life: “Quit India,” he told the British. Linlithgow promptly sent all national leaders to jail, throwing India into turmoil.

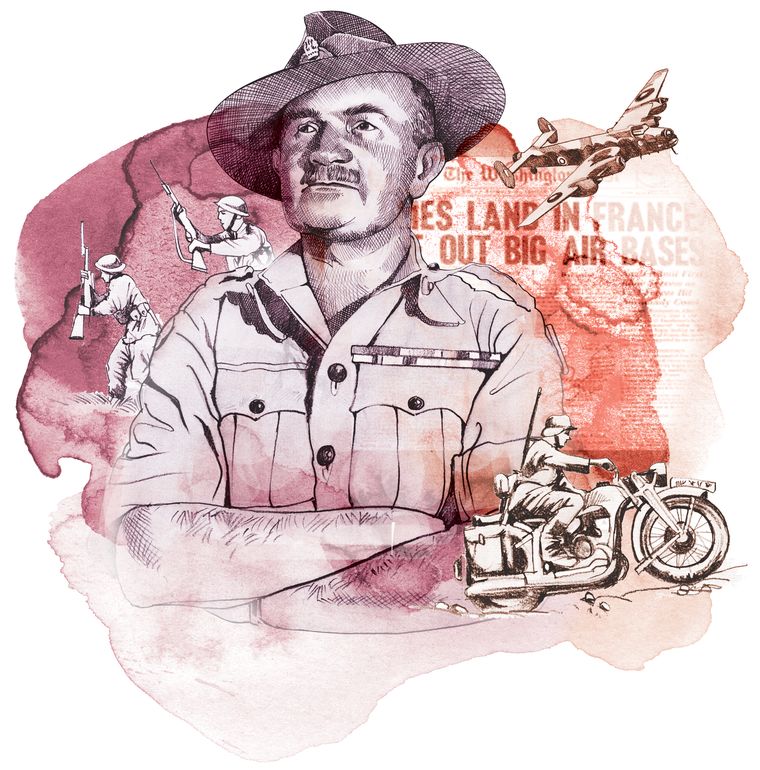

Meanwhile, Bose’s efforts to rally German aid for Indian freedom got nowhere. The Germans told him to seek the help of the Japanese, who were fighting the British in Asia. Bose undertook a submarine journey to the east and reached Tokyo. The Japanese gave him charge of 60,000 Indian prisoners they had taken from Malaya and Singapore. He took them to Singapore, where Rash Behari Bose handed him the command of the Indian National Army.

With about 25,000 of 60,000 surrendered Indian troops, Bose joined the Japanese march towards India. By then the Indian Independence League of Japan had sent 14 men in four groups by land and sea to spread the seeds of revolt in the Indian Army, but they were captured and executed by the British.

In October, London recalled Linlithgow and appointed Wavell, the well-loved general who had commanded Indian divisions in North Africa and had been impressed by them. But he had not impressed Churchill, who had sent him as C-in-C of India and now viceroy. Within days, the Andamans fell to the Japanese who handed over the islands to Bose. As Bose hoisted the Indian flag there, Japanese bombers were pounding Calcutta.

Wavell, a man with poetic imagination (he used to compose verse even on the battlefield) and military common sense, realised that the situation was getting precarious on three grounds. One, thousands of Indians were dying in a famine in India after the fall of Burma, from where rice used to be imported.

Two, Wavell’s military mind understood that the Japanese could not be stopped anywhere in Burma and they would invade India. By March they were knocking on the gates of India at Kohima and even planted the INA flag on a corner of the Indian soil. With the presence of so many Indians in Bose’s ranks fighting alongside the Japanese, there was no guarantee that even the most loyal Indian mind would not turn against the British.

Three, Gandhi’s health was deteriorating in the Aga Khan Palace, where he was incarcerated. Kasturba’s death in prison, too, had devastated him.

In May 1944, Wavell released Gandhi. Gandhi told Wavell’s emissaries that he was willing to withdraw civil disobedience and offer full support to the war if Wavell could at least promise freedom soon enough. Once again, Wavell found his hands tied by London.

Fortunately, the war was turning favourable. Having evacuated the entire army from Arakan in Burma with American aid, Gen William Slim decided that Britain would take its last stand at the gates of India. The battles on the Indian frontier would ultimately decide the destiny of the so-called free world.

The gamble paid off. Indian and British troops fought what they thought was the final battle at Kohima and Imphal, where they finally blocked the Japanese. For Indians, it was the last chance to save India from another tyranny. For the British, it was the last chance to save the free world and exit from the empire with honour.

Most military historians say the battles of Imphal and Kohima were among the worst and the fiercest ever. For the first time since the war had begun, the Japanese land advance was halted. On July 8, 1944, Gen Renya Mutaguchi accepted failure and ordered the remnants of his army to withdraw. India was saved.

Slim came to be known as the man who saved India. But in his hour of glory, he would not rest on his laurels. In a brilliant counterattack, Slim sent his Indians to chase the Japanese across the river Chindwin, into the Irrawaddy basin, into Rangoon and beyond, in what he himself described as “a forgotten war”. Slim would later declare with pride: “My Indian divisions after 1943 were among the best in the world. They would go anywhere, do anything, go on doing it and do it on very little.”

The victory strengthened Wavell’s hands. He could now persuade the home government to divert food supplies from Australia and elsewhere to India.

With the Japanese in retreat, and the INA having surrendered or been captured, Wavell invited the Congress and Muslim League leaders to a conference in Simla in June 1945. Slim was planning an amphibious invasion of Japanese-held Malaya with his British and Indian forces when US president Harry Truman atom-bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki and brought a quick end to the war. Within a week, Bose was reported killed in an aircrash in Formosa while trying to escape to Russia.

The final surrender of the Japanese was accepted on September 12, 1945, by Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia Command, who would preside over the transfer of power in India. But as the British moved to try INA officers and troops at the Red Fort in Delhi, protest broke out across the country. Nehru, who had political disagreements with Bose and the INA, himself donned the barrister’s gown and went to defend them along with eminent lawyers like Bhulabhai Desai. The protests drove home a message to the British, that the loyalty of Indians could not be taken for granted any longer. India was ready to be free.

Saner counsel prevailed on Wavell and his C-in-C Claude Auchinleck, both of whom had commanded Indian troops in war and in peace. Early January, they freed the INA men unconditionally. Parting from India, they realised, had to be with honour, or at least without rancour.

Within a month and a half, they received the final warning, too. The sailors of the Royal Indian Navy rose in revolt in February 1946. Finally, it needed persuasion by Indian national leaders for the rebels to call off the mutiny.

By now the British were reading the writing on the wall: They had won the war with India’s help; now it was time to leave India to Indians.

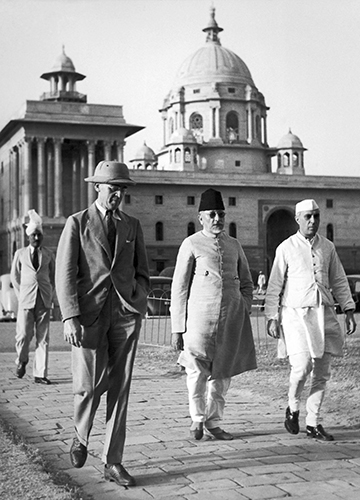

London sent one last delegation, the Cabinet Mission, to make the parting as friendly as possible. The members were chosen carefully. Heading it was, of course, the good old leaf-eating leftie Sir Stafford Cripps. One of the two other members was Lord Pethick-Lawrence, a pacifist Labour leader known in England as ‘Gandhi in a suit’.

The rest is history—of the dawn of freedom and the birth of the largest democracy in the world.