TOO MANY COOKS do not spoil the broth.

Rather, they enrich it. That seems to be the lesson from India’s tryst with its telecom destiny in 1999.

The cooks in this case were no fewer than a dozen. From March 1998 to October 1999, there were nine ministerial changes in the department of telecommunications. A change of guard every three months.

Bureaucrats, too, spun in and out through the revolving door, even as a high-power committee set up by prime minister A.B. Vajpayee and led by the deputy chairman of the Planning Commission hammered out a roadmap for the much-needed reforms.

In April 1999, the Vajpayee government dished out what the sundry cooks had prepared—a comprehensive, futuristic telecom policy that would be chicken soup for the ailing sector. NTP-99 (as industry honchos began to call the new policy) created a lasting framework for a world-class telecom ecosystem in India. It envisioned private and public companies competing to build infrastructure, finding solutions to obstacles, providing quality services, and keeping customers, shareholders and regulators happy. NTP-99 also mandated the hiving off of state-owned operators like Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd as distinct corporate entities, freeing the telecom department to play the role of a fair umpire in the fledgling sector.

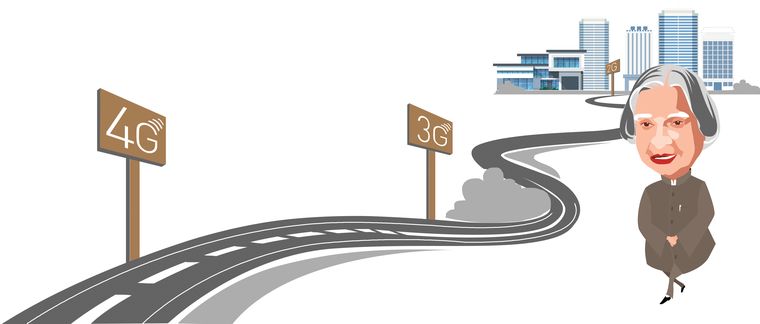

India’s telecom revolution was built on this policy bedrock. At the time NTP-99 was unveiled, only three of every 100 Indians had active phone connections. By the time the government deemed it necessary to update the policy, in 2012, India had 70 active connections for every 100 individuals.

NTP-99 also helped create two of the most valuable companies in India’s post-liberalisation era—Airtel and Idea Cellular. “NTP-99 exhibited a coherent thought process and introduced the principles of a level playing field,” wrote Sanjeev Aga, managing director, Idea Cellular, in 2010.

The policy had its fair share of critics, too. Some said it would cost the government Rs50,000 crore, as it introduced a revenue-sharing system in place of an entry-fee regime. Existing operators who owed thousands of crores to the exchequer were allowed to switch to the new system without having to pay up their dues. This so riled opposition parties and left-leaning analysts that they labelled it as a scam.

Also, barely two weeks after NTP-99 was introduced, the government lost a trust vote in the Lok Sabha. President K.R. Narayanan wanted to defer the policy until a new government was in place, but Vajpayee pushed it through with support from admiring bureaucrats and stakeholders.

Aruna Sundararajan, who became Kerala’s founding IT secretary in 1998, calls NTP-99 “one of the most transformational policies of all time”. “There is no other success story which really can be compared to India’s telecom growth,” she told THE WEEK. “NTP-99 was brought about because the first telecom policy of 1994 [did not achieve] its targets. The players were struggling, and the whole sector needed a relook. Around 22 million phones was the penetration at that time. By 2015, we had achieved one billion connections. Nobody actually expected this kind of growth.”

But, it was good only while it lasted. When Sundararajan took over as telecom secretary in July 2017, the sector had come full circle. The number of operators in India had halved because of brutal competition and costly spectrum. Also, the debt owed to the government under the revenue-sharing system was piling up. Unable to cope, many operators had shut shop, while others began to explore merger options. Some operators alleged that regulatory flip-flops had benefited Reliance Jio, which had become a dominant player because of its cheap data plans.

For two years, Sundararajan steered the sector through turbulent times. In 2018, she oversaw the release of a new policy that envisioned investments worth $100 billion, creation of four million jobs and the rollout of 5G technology. The new policy was christened the National Digital Communications Policy 2018. The shift in nomenclature was significant—voice-driven telecom was out, data-driven digicom was in. The 30-year-old Telecom Commission, of which Sundararajan was ex officio chairperson, was suitably renamed as Digital Communications Division.

Sundararajan believes that Jio became the dominant player not because of policy flip-flops, but because its competitors were overtaken by technology. “They were a little late in seeing the data revolution happening globally,” she said. “They thought the revolution here would happen only two-three years later; and that they had time to start upgrading their network. But the revolution happened sooner because of Jio.”

But, it is not just Jio’s rivals that are paying for their miscalculation; it is the consumers as well. As operators struggle to invest in infrastructure, the quality of services has gone down. The penalties on operators who did not meet the government’s benchmarks peaked last year. Mobile internet speeds also remain pitifully slow—India was 128 among 140 countries in the Speedtest Global Index in December 2019, lower than Pakistan, Congo and Libya.

The 4G battle has been devastating for the telecom sector. Only four operators remain, and all except Jio are struggling to pay dues that now amount to 01.5 lakh crore. The battle to roll out fifth-generation networks by the end of this year has already begun, and there are fears that it could push the sector into a duopoly.

Sundararajan, who retired last July, is hopeful that the market will find its way out of the mess. But, she said the government would do well to recognise the constraints in the sector and “rationalise” the spectrum costs involved. “If India does not have a strong digital infrastructure, we would be losing out on economic and social benefits,” she said. “So when I say that the spectrum prices are high, I am not concerned about operators not making profits. My point is: If we want to provide good-quality digital infrastructure to our citizens, then yes, costs must come down.”