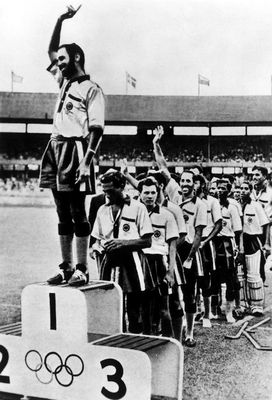

Summer Olympics: 1948, 1952, 1956. Gold medals: Three. Shirt number: 13. Name: Balbir Singh Dosanjh. India’s oldest living Olympic hockey medallist (95) is regarded as one of the greatest centre forwards ever, and was captain of the Indian team for the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. He scored five goals in India’s 6-1 victory over the Netherlands in the final, at the 1952 Helsinki Games, an individual record that still stands. Balbir Singh Sr, as he is known, is the only remaining link to Indian hockey’s golden era.

Sprightly for his age, he continues to grace sporting events in his trademark suit, matching red turban and tie. Over the last year, he suffered from bronchial pneumonia, and was on life support for some time, but fought hard and was discharged after being hospitalised for 108 days. He recently flagged off a youth cycle rally from his home in Sector 36 in Chandigarh. Balbir Singh Sr’s never-say-die spirit exemplifies the spirit of the Sikh community.

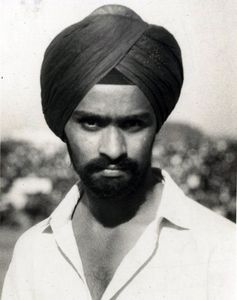

About 5km away, in Sector 8, lives another legend of Indian sports: Milkha Singh, who came fourth in the 400m final at the 1960 Rome Olympics. Milkha may have missed the bronze by a whisker, but he became known world over as the “Flying Sikh”. “It was certainly a proud moment to get the title from [former Pakistan president] General Ayub Khan after I beat Abdul Khaliq during a fairly emotional visit to Pakistan,” Milkha told THE WEEK. “It gave me a lot of visibility. Sikhs were recognised in sporting circles as well, thanks to this title.” Milkha has experienced many tragic moments, none worse than seeing his parents and siblings die in the riots during Partition. But as a devout Sikh, his faith has helped him overcome adversities. “I believe in God,” he proclaimed. “I have faith that He will do the best for us, and that faith has been rewarded. Look where I came from and the life He bestowed on me.... Sikhs have given their lives for our nation. My fellow Sikhs also used to train like that. They were willing to give it their all.”

Milkha’s contemporary, Gurbachan Singh Randhawa, was no less special. Winner of the decathlon gold at the 1962 Asian Games in Jakarta, Randhawa will always be remembered for his fifth place finish in the 110m hurdles finals at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

Milkha’s son, Jeev, has carried forward the family name in sports when he became the first Indian golfer to play on the European Tour. In 2006, he also became the first Indian to break into the top 100 of the world golf rankings. Jeev’s success abroad inspired a golf revolution in India.

“Everywhere I go, they recognise me as a Sikh player from India, as Milkha Singh’s son,” said Jeev. “I was playing in the PGA Championships and my name was on the leader board. When I went to the first tee the next day, there were Indians, a lot of them Sikhs, waiting with posters that said ‘Singh is King’.... These moments make me feel proud of my community and identity as a Sikh and Indian.”

Kamaljeet Singh Sandhu was the first Indian woman athlete to win a medal in any international competition. She won the gold at the 1970 Bangkok Asian Games in the 400m race. She was a forerunner to famous women sprinters like Geeta Zutshi, P.T. Usha, Ashwini Nachappa and Shiny Abraham.

About 150km from Chandigarh is the village of Sansarpur, aka the cradle of Indian hockey. The village has seen its players win 15 Olympic medals, a record in itself. The likes of Col Balbir Singh Kullar and Ajit Pal Singh came from here. Ajit Pal captained India to its lone World Cup victory in 1975, when Balbir Singh Sr was manager. “It was natural for me to take up hockey,” said the 72-year-old Ajit Pal. “I grew up watching seniors play in the ground and we would be made to stand alongside the boundary to fetch the ball. If you looked at the Indian team of that time, out of 18 players, seven to eight came from Punjab.”

The state also gave India outstanding players like Harbinder Singh, Gurbux Singh and Prithipal Singh, around the same time. The likes of Gagan Ajit Singh, Rajpal Singh, Sandeep Singh and Sardara Singh have showcased the best of Indian hockey in recent times.

In athletics, much before Balbir Singh Sr or Milkha Singh burst on to the scene, long jumper Brigadier Dalip Singh Jatt was the first Sikh to represent India in the 1924 Paris Olympics. He would have not made it without the backing from Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala. A sportsperson himself, Bhupinder Singh and the royal house of Patiala created a sporting legacy in India. His grandson, Randhir Singh, was the first Indian to win a medal in shooting, at the 1978 Bangkok Asian Games.

“[Because of the] interest shown by the maharajas, a lot of sportspersons came out,” said Randhir, 73. “Being a martial race, Sikhs were very keen to showcase their skills, be it fencing or riding. Patiala became the house of cricket. Maharaja Bhupinder Singh was the captain of the Indian [cricket] team that visited England. Patiala’s cricket and polo teams were among the best in India.”

Perhaps the biggest impact in Indian cricket by a Sikh was made by the finest exponent of left-arm spin—Bishan Singh Bedi. Making his Test debut in 1966, he went on to lead India in 22 Tests, succeeding Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi. Bedi was the first Sikh to lead the Indian cricket team in independent India.

“Cricket, to me, is a highly spiritual exercise,” Bedi told THE WEEK. “It gave me my Sikh identity and vice versa. What cricket imbibed in me is also what Sikh tenets are about—honesty.” Bedi then quotes the most important words in the Guru Granth Sahib, the Mool Mantra: “Aad sach, jugaadh sach, hai bhee sach, Nanak hosi bhi sach (True in the beginning, true throughout the ages, true even now, Nanak truth shall ever be).”

The bright patkas (head wraps smaller than a turban) he wore would stand out. “Before I went to England for the first time in 1967... my mom [cried]. I asked her what happened and she said, ‘I don’t know whether you will come back or not. And if you do, will you look the same?’ she lamented. That was a learning,” said Bedi.

“I played with a turban from 1967-69. In a Test versus Australia, it was very hot and the turban would loosen. I told Tiger [Pataudi] I was going in with a patka and he said: ‘You can go in your birthday suit if you like, as long as you are there!’ That is how the patka started. Looking different did not make me think I am the only one. Rather, it made me humble.”

Two years after Bedi retired, came Navjot Singh Sidhu, a stroke player with a mind of his own. Left-arm spinner Maninder Singh came close to continue the tradition of left-arm spin that Bedi gave to Team India. A few years later, a young 18-year-old from Jalandhar made his way into international cricket with his off spin. Harbhajan Singh would go on to become one of India’s most successful spinners ever.

With women’s cricket finally finding its wings, one cannot but mention team India’s T20I captain Harmanpreet Kaur. Her match-winning knock of 171 in the 2017 Women’s World Cup semifinal against Australia will be etched in cricket history for ever. Kaur and her teammates have created a legion of fans, which the women’s game did not have earlier.