Right in front of Rashtrapati Bhavan’s new ceremonial hall hangs a most curious painting on Mahatma Gandhi—a giant impressionist oil-on-canvas by Polish-born British artist Feliks Topolski. The description next to the painting offers the most familiar strand of mystique associated with it.

“[The painting] ... shows Mahatma Gandhi bathed in blood leaning on two young women, calmly slumping to the ground. It was painted in 1946, as if in precise premonition of Gandhiji’s assassination two years later. It was later re-worked as part of a large four-panel painting titled, ‘The East 1948’ which Pundit Jawaharlal Nehru acquired on a visit to London in 1949,” it reads. Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated on January 30, 1948. But could Topolski really have foreseen the precise details of his killing? At the heart of this mystery are two paintings: one done in 1946 and a reworked version in 1948.

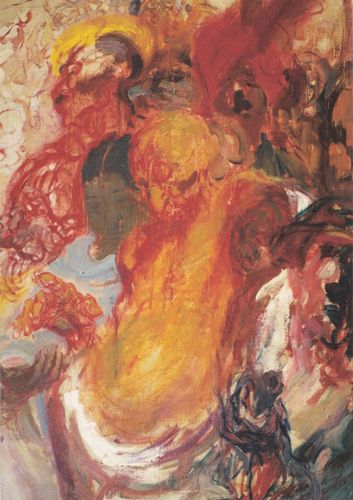

The version displayed at the Rashtrapati Bhavan Cultural Centre has a collapsing figure of Gandhi in his blood-stained loin-cloth, being carried by two women, and surrounded by a sea of shocked faces. Prominently, there is another man, with his back facing the onlooker, holding two terracotta pots. The richly detailed painting has an atmosphere of chaos. However, the Rashtrapati Bhavan art collection e-catalogue has titled the painting as ‘Assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, 1946’.

The original 1946 painting can be seen as frontispiece in a 1953 book titled Sketches of Gandhi, compiled by Gandhi’s youngest son, Devdas, who was managing editor of the Hindustan Times at the time. It does not have much blood or chaos. Devdas wrote in the foreword to the book that the painting shows “a profoundly calm but limp figure of Gandhiji just prevented from falling by the support of his companions... his right hand, half raised in doubt and pain.”

There is a black pipe-like object protruding from the bottom-right of the 1946 painting. This has been interpreted as a gun barrel and spawned a premonition theory. But why is the gun pointed towards the viewer? “Critics have described it as the artist’s premonition of the assassination... the artist himself has neither denied nor confirmed the theory,” Devdas wrote.

Topolski had been Britain’s official war artist during World War II. He first visited India in 1944 while undertaking an extensive tour of China, Burma, the Middle East and Africa. He penciled a number of Gandhi sketches during this visit. Gandhi never really gave any sittings for his sketches. But Topolski effortlessly captured the cadences of the dynamic leader by shadowing him around.

But could Topolski have really gotten away with predicting the Gandhi assassination in 1946 without a modicum of a controversy? Or, was the intuitive artist just portraying a tired Mahatma, in the last lap of his freedom struggle which was not quite panning out in the way he had hoped, with escalating communal divisions? Is the “premonition” aspect simply a superimposed idea since we are seeing the painting in hindsight? And, who has seen the original 1946 painting, and to what extent was it further developed?

“We at Rashtrapati Bhavan only have this one painting which came here around 1951,” says a staffer associated with the museums and art collection at Rashtrapati Bhavan. The staffer was involved in physically shifting the 380x380cm painting to the cultural centre in 2014 from the grand staircase area where it was first displayed for more than a decade. “We have not seen the original 1946 painting and we do not know who owns it,” he says. “But it is true that the idea of this painting was conceived even before Gandhi’s assassination. I have seen an article by Gopalkrishna Gandhi which confirms this.”

Also read

- PM Modi pays homage to Mahatma Gandhi at Rajghat

- Rediscovering peace at Gandhi's Sevagram Ashram

- 'Tatva' of Gandhi's philosophy remains same, 'tantra' will differ

- Mahatma Gandhi's ideas for the world

- Many faces of Gandhi

- The unknown Gandhi: The extraordinary journey from Mohandas to Mahatma

- Canonising Gandhi made him a myth more than a man: Mark Tully

- What Gandhi wanted for India

- Gandhi was not a caste abolitionist: Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd

- Gandhian philosophy needs to be practised: Tushar Gandhi

When THE WEEK reached out to Gopalkrishna Gandhi, former West Bengal governor and the son of Devdas Gandhi, he humbly revealed that an error had been pointed out in an article he wrote extolling the Rashtrapati Bhavan painting on January 30, 2016, in the Hindustan Times, that the painting in question was completed after the assassination in 1948 and there was another one painted in 1946. The error was flagged by US-based art historian Sumathi Ramaswamy. Considering that the information on the painting on the Rashtrapati Bhavan website was last updated in 2014, and the HT article appeared in 2016, is there a cataloguing error which is perpetuating an unconfirmed theory?

Ramaswamy, professor of history and international comparative studies at Duke University, North Carolina, has done a fair bit of research on both the paintings. According to her research, the 1948 painting was brought to India in January 1950 when Topolski was invited by Nehru for the Republic Day celebrations. She has noticed differences in the two paintings even though there are several similar elements. “Notice the presence, in the bottom right of the canvas [in the 1946 painting], of a disembodied hand with a smoking gun pointing towards us,” she says. “In the 1948 painting, notice a dark figure has been placed behind the gun.” She adds that there had been attempts on Gandhi’s life by 1946, and that explains the gun. Was Topolski aware of that? Ramaswamy, too, has not seen the 1946 painting in its original form, but she hopes to uncover more details soon.

She might have a lead from the artist’s daughter Teresa Topolski. Teresa confirms that the frontispiece in Sketches of Gandhi is an authentic reproduction of the 1946 painting. The original, she says, resides with a certain Burstyn family in Canada. That is all she says she knows. About the so-called prescient nature of her father’s painting, she would rather not ruminate much: “I do not have an opinion on the painting. How could I? Feliks himself did not confirm or deny, he was not Cassandra.”