Ten-year-old Tina’s summer vacations seem to have been extended. It’s early August, but the Class 6 student has not been to school yet. “She just watches cartoons all day. She loves Pokemon!” said Rina, her 13-year-old sister, giggling.

Tina stays at home through the day, watches “cartoons and films with mother” and has a siesta, said Rina. Some evenings, the sisters play badminton. Every now and then, they experiment with their mother’s eyebrow pencil, or even her bright pink lip colour. “Sometimes, she draws too,” Rina told me, while on her way back from school on a hot, humid afternoon in Chandigarh.

The family of four lives in a one-room house, with bare brick walls and a tin roof covered with dry twigs. These days, there is a constant trickle of visitors—reporters pleading with the mother to let them meet Tina, social workers asking after her health, NGO professionals offering assistance, and policemen following up on the case.

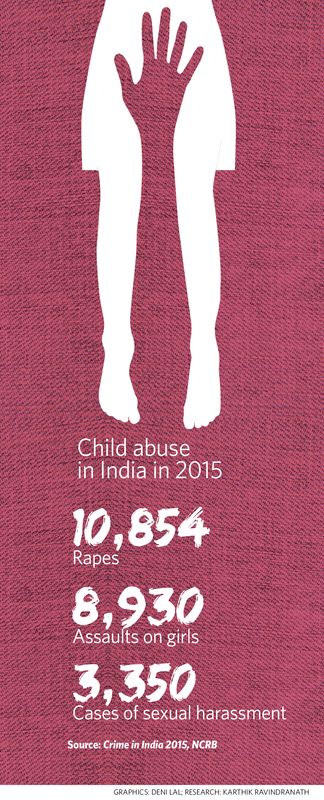

Tina, the chubby pre-teen who “loves chocolates”, is about 32 weeks pregnant. In mid-July, the family discovered that she was pregnant; her ‘uncle’—a relative of her mother—had been raping her for several months when the mother was out for work. A report was filed against him, resulting in his arrest. Subsequently, the family approached the local court seeking permission for an abortion.

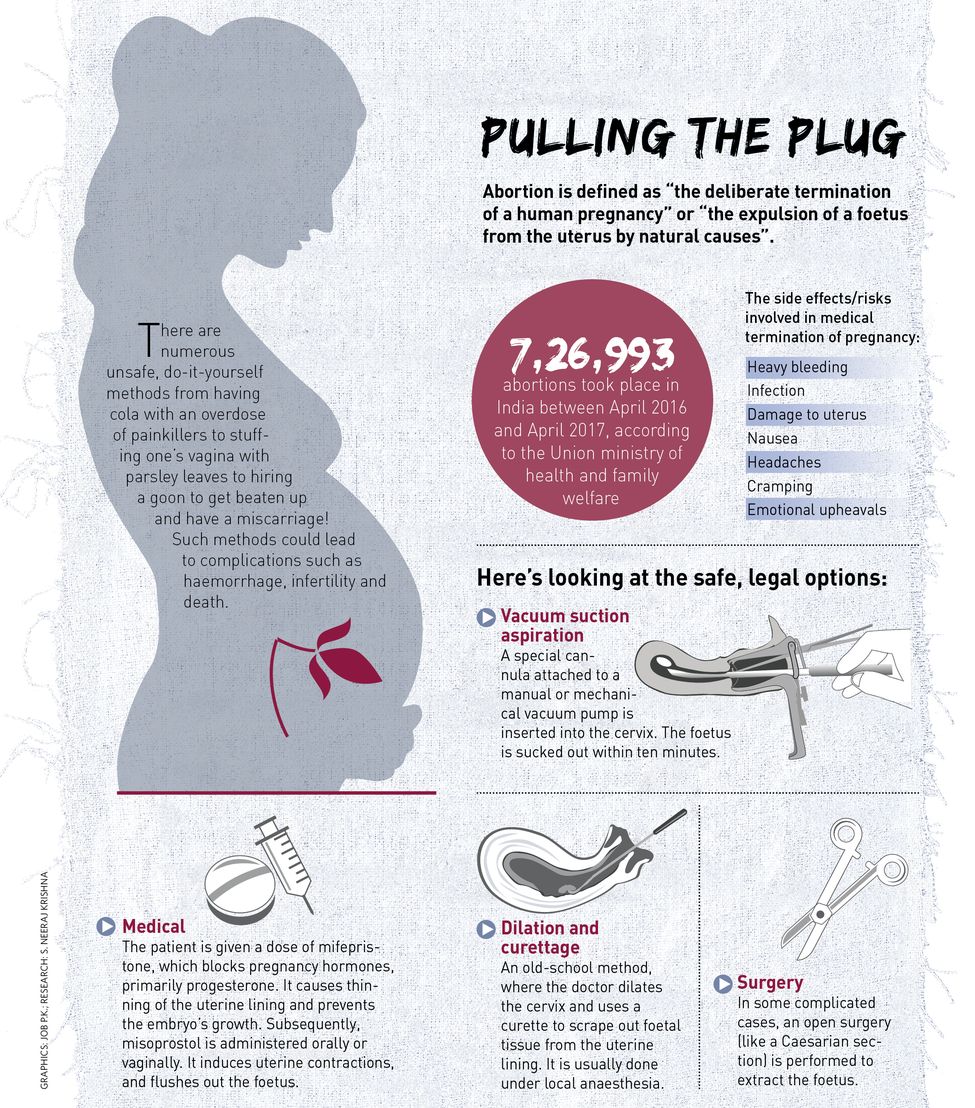

The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971, does not allow abortion after 20 weeks of pregnancy, unless it is a threat to the life of the woman. But, the court can decide after the ceiling. In this case, the district court asked the Government Medical College and Hospital (GMCH), Sector 32, Chandigarh, to constitute a committee to examine the medical merits.

A doctor from GMCH, who was on the committee said the duration of the pregnancy was confirmed at about 30 weeks then, and since the foetus was legally viable now—or as it had a life of its own—it could not be aborted. Hence, the court turned down the family’s plea.

Then, Alakh Alok Srivastava, a Delhi-based advocate, filed a petition in the Supreme Court. On July 28, after a committee of doctors from PGIMER, Chandigarh, filed its report, the Supreme Court, too, dismissed the plea. The court also suggested that permanent medical boards could be set up in states to look into similar cases.

With the courts refusing relief, Tina is in for a tough battle. A Caesarian section is most likely, and there are multiple risks including high blood pressure (pre-eclampsia) and infections, said a doctor from PGI. “As such all teenage pregnancies are high-risk, and this child is even younger. The survival rate of the baby is also low in such cases,” said Dr Suneeta Mittal, director (obstetrics and gynaecology), Fortis Memorial Research Institute, Gurugram.

Even as the complex debate around abortion versus the risk of pregnancy continues, Tina’s family is finding it hard to deal with being in the spotlight.

Since the night of July 14, when the case was filed, the local press has been following the story relentlessly. Perturbed, the parents have clammed up and Tina has been confined indoors. Every now and then, as the dark blue wooden door of the house opens, one gets a glimpse of the family’s meagre possessions—a bed, a TV, a desert cooler, and a refrigerator. A white Maruti 800 parked outside the iron gate, is, ostensibly, used sparingly.

Each time there is a visitor at the gate, a chubby face peeps from behind the iron grille of what seems to be the only window of the house. Tina smiles, and then bows her head, perhaps, as instructed by her parents. Her girlfriends from school have not visited her. “They have no idea what has happened,” school authorities insisted. Among the few who are allowed access to her, two are social workers appointed by the state department of social welfare.

“Go away. I am a poor man... This has become [a] business for you people... We don’t want [any] sympathy. Nothing. You want to make money out of this. This my personal matter, none of your business,” an irate, inebriated father said in his broken English, when I first visited their house. “For more than 20 years, I have worked hard... built a reputation among [my] bosses. All is finished. Leave, or I will call the police. And, leave your id proofs here. You can’t run away.”

Neighbours say that the father is in “shock” and has been “beside himself” with anger. On a subsequent visit to the house—sandwiched between two sprawling official bungalows of government officers—a neighbour told me that life was normal for the family, until about two weeks ago. In the morning, the father—a short, stocky man, who “drank occasionally”—would leave for work at a government office where he is a watchman. The mother, too, would be at work. She is a domestic help at the neighbouring bungalow of a government officer. The sisters would be at school. About a year ago, Tina had been home more often, after a surgery to repair a hole in her heart.

“The family is from Nepal,” a neighbour said. “The mother has at least two brothers, and one of her sisters-in-law works as a domestic help in our house. They are hardworking folks. The other ‘brother’ [the accused] is actually a distant relative of hers who worked at a hotel. His family is in Nepal.” All family members were “close” and spent time at each other’s place, particularly the accused, who was seen more often at the girl’s house. “We often wondered why the mama would hang out so much at their house,” the neighbour said. “He was a shy man, who always kept his eyes lowered, and never even dared to look up at any of us.” The area in which they live is pretty safe, said another neighbour. “Who could have thought that she was not safe inside her own house?”

No one had suspected a thing. Until Tina’s swollen belly aroused suspicion among the local women. “At first we thought it could be a reaction of the medicines that she had been taking after the surgery,” said a neighbour. “But then, another woman pointed out that the shape of her belly was like that of a pregnant woman. We could have never imagined such a fate for a small girl.” The neighbour’s daughter said the little one who “loved rice” had lately been feeling nauseous at the sight of rice, or even peas.

Curious, the neighbour, a homemaker in her late 40s, asked the mother why the girl had been putting on so much weight. “I asked her whether she was getting her periods regularly,” she said. When the mother said that the daughter had missed her period for at least “four-five months” the neighbour raised an alarm. “I told her you must drop all work and go to hospital right away.”

The family bought a pregnancy test kit that evening and were shocked when the girl tested positive. On being questioned, Tina told her parents about the ‘uncle’ who had been raping her for months. She said he told her he would do the same to her sister, if she complained. Soon, a complaint was lodged with the police. Tina was examined by doctors at a local hospital. The ‘uncle’, who had “no time to run away”, was arrested within a couple of days.

The parents are understandably hostile towards visitors, particularly journalists. “Quick. I have no time for all this,” her mother told me gruffly. “Because of all of you, even those who didn’t know [the school authorities] are aware of our situation now.” The stocky woman in her mid-30s agreed to speak after much persuasion.

How is Tina’s health? “Theek hai (She’s ok).” Does she need anything I could get? “Kuch nahi chahiye (We don’t want anything).” Does the family have a lawyer? “I don’t know. Ask my husband.” Does Tina know about her condition? “No. She is small. We haven’t told her anything.”

On a cool Monday evening, after a brief spell of rain, I watched Tina step out of the wooden door, go past the small corridor, past the iron gate that stays locked through the day. Outside their house, life went on as usual. The neighbours’ SUVs breezed in and out. Except one or two residents from the bungalows, no one stopped to chat with the domestic help.

The girls were planning a game of badminton. For now, they were chasing a litter of black puppies. As the girls played, their mother stood guard. As soon as she spotted me, Tina was signalled to get in immediately. Sporting a long ponytail, her printed shirt and matching pyjamas just about hiding her swollen belly, she hastily stepped inside.

At her school, a short rickshaw ride away from the house, I searched for more clues. “We had no idea this could happen,” the headmistress said. “I could not believe it. When the police came to us to confirm her date of birth, I said ‘This couldn’t be! She couldn’t be a kid from my school!’”

The school counsellor, a soft-spoken woman, recalled that a few months back, the girl had felt dizzy and fallen. “We had called her parents and asked them to get her treated,” she said. “We even asked them if they needed any help. But they refused, and said it could be because of her heart issue.”

She said the parents allowed her to meet Tina only after much persuasion. “I met her briefly, and figured she was doing fine,” she said. “She greeted me with ‘Hello, how are you, Ma’am?’ She told me she would like to come back to school. I said, ‘I had explained to you kids about good touch, bad touch. Why didn’t you tell me anything?’ But, she kept quiet.”

Teachers described Tina as an “average” student. Her neighbour, however, said she was a “bright kid” who sought help with her homework. “Just some time back we had helped the sisters with their holiday homework,” the neighbour said.

Rina said she liked maths and wanted to be a maths teacher, but her younger sister liked English more. “She reads her English books now,” said Rina, adding that her father wanted the younger one to be an engineer. “I am very scared of my father,” she said with a laugh.

The father was himself pursuing a part-time management programme, and he and his wife wanted their daughters to get a good education. “They have big dreams for their daughters,” a neighbour said. “Now, whenever I see her mother, she just stares at me blankly. The only thing they want now is phaansi [death penalty] for the accused.”

The social workers who visit them every day said Tina was doing fine. “We are only trying to help prepare her mentally for the months ahead, and her delivery,” one of them said, as she stepped out of the house. “The parents can keep the baby or surrender it to the government.” She said schools should have counselling sessions from Class 5 onwards, to educate children about “good touch, bad touch”.

How was Tina doing? “We have been reading in the local papers about how she knows about a ‘baby’ inside her,” said the social worker. “Fact is, she doesn’t know anything. She has been put on a special diet, and thinks she is unwell, that’s all. The department of social welfare will arrange for a tutor so that she does not miss out on her studies.”

But the situation was sensitive, she said. “In a way, we have already made her ‘special’ by giving her all this attention,” she said. “Why force her to revisit the trauma by asking her difficult questions? We are telling the parents that it’s not her fault, and this is not a matter of shame for them.”

Advocate Sneha Mukherjee of Human Rights Law Network said the administration had assured her that Tina would get the best of medical care, and the baby would be handed over to the state. The parents did not want to keep the baby, she said.

For now, they are just concerned about their daughter. One of the social workers told me, “They keep saying, bacchi ki jaan bacha lo, usko kuch nahi hona chahiye (Please, just save her life. Nothing should happen to her).”

(Tina and Rina are fictitious names.)