I hope to be the women’s world squash champion one day. Inshallah,” said Maria Toorpakai Wazir, Pakistan’s number one woman squash player, smiling affably and dressed like an international sports star in the making. Few would imagine the 24-year-old is under threat from the Taliban for pursuing the sport. She was on a book tour across America, promoting her memoir, A Different Kind of Daughter. The book is an amazing read but nothing compares to meeting her in person. Maria’s story of courage began when she was just four years old. Disturbed by the ill treatment of girls, she cut her hair short, burned her girly clothes and disguised herself as a boy so “she could live a free and full life.”

Her father, Shamsul Qayyum Wazir, named her Genghis Khan after the great Mongol warlord. True to her alias, she forged an emotional, mental and physical identity that would change her destiny and put her on the path to playing squash. Maria is today on the way to fulfilling her dreams, training in Toronto, Canada, under the mentorship of Jonathon Power, the first North American squash player to reach the World No 1 ranking in 1999. But the journey to Toronto cost Maria and her family much—blood, sweat, tears and their home in Waziristan. It is a tribal region in northwest Pakistan bordering Afghanistan and a Taliban stronghold.

Neither Maria nor her family regrets standing up for their beliefs. Her father, who is a teacher, and mother, Yasrab, a school principal, homeschooled their children, defying conservative society, and treated their daughters, Maria and Ayesha, on a par with the sons—Taimur, Sangeen and Babrak. Ayesha Gulalai, too, is a trailblazer, being the first tribal woman member of parliament in the Pakistani National Assembly.

“We are warriors,” said Maria. “I never back down from a fight.” As a result, she would often return home bloodied and dusted up. After one too many dangerous fights with boys, her father decided to channel her aggression positively to sport. Not just any sport, weightlifting! Few girls would have dared to take on such a challenge, but Maria trained hard for competitions, her muscular build a fitting testament to her efforts. Squash might not have grabbed her mind if puberty had not upset her well laid plans.

With her body changing, getting past bare-chested weigh-ins, as is the norm in weightlifting, was proving to be a challenge. At the Under-16 boys weightlifting championship in Lahore, competing as Genghis Khan, Maria narrowly escaped having to weigh-in in a state of near undress. And though she won the silver medal, Maria recalled brother Taimur’s words of caution: “If they ever find out what you did in Lahore, defeating the boys like that, they will hunt you down and kill you.” She, however, was secretly excited that she had bested the boys without them knowing she was a girl. Shamsul masked his concern with humour, commenting she would “get him in trouble if she continued with weightlifting.”

Queen of the court: Maria Toorpakai with her coach at the 2014 Asian Squash Championship, Pakistan | Getty Images

Queen of the court: Maria Toorpakai with her coach at the 2014 Asian Squash Championship, Pakistan | Getty Images

Thankfully, Maria soon fell in love with “the giant glass cube” in the vicinity. She decided to switch from weightlifting to squash and enrol at the squash academy run by the Pakistan Air Force. With just one document required to complete enrolment, the recruiting officer told her: “Now all we need is your birth certificate.” With that, the secret life of Genghis Khan crumbled.

Left with no choice, Shamsul confided in Wing Commander Pervez Syed Mir, the academy director, that Genghis Khan was a girl. With one word—“Welcome”—Mir handed her a limited edition Jonathon Power racket, became her coach and ignited a passion for the sport. Maria describes squash as “Allah’s gift to me.”

But what did it feel like to go back to being a girl after living like a boy for more than a decade? “Sometimes during my weightlifting days, I would look at myself in the mirrors as I lifted the weights and barely recognise the beefy, muscular boy looking back at me,” she said. “At times, I felt I no longer knew the real me. Not on the inside and certainly not on the outside. To me, it was just about feeling [like] a free human, and that’s all it is even today. But I was sure that I could not live a life imprisoned within the four walls of a house.”

Girls imprisoned within homes, in child marriages, slavery and prostitution, and people imprisoned indoors for fear of death lurking in bazaars and places of social gatherings—she had seen it all growing up. Living in a Taliban stronghold introduced her to firearms training. One day, armed men came into their home, forcing them to flee for their lives. The next day, her father taught an eight-year old Maria “to aim and shoot with a Makarov pistol to protect the family and self.”

However, even firearms training did not prepare Maria for the battle that came next. One day during squash practice, her coach let slip her gender identity when he addressed her by name. Maria felt the dramatic change in her situation in a split second. Their male egos bruised, fellow competitors who had until then shared her passion for the game began gender stereotyping. Her skinned and bloodied knees, aching muscles, sportsman spirit and athletic force on court did not matter; she was a girl, a tribal girl at that. As word about “the Pashtun girl on the squash courts” spread, the boys showed up—leering, jeering and making sexual innuendoes.

Maria braved the bullying and let her game do the talking and winning laurels. The Wah Cantt Under-13 Tournament in 2002 being her first title. She won the under-15 and the under-19, was seeded number 3 at the Asian junior championships and clinched the National title. “It is written,” she said, borrowing her mother's favourite phrase that she was destined to succeed.

After 9/11, Pakistan saw a surge in Talibanisation, and her family received a direct threat. A letter left on her father’s hatchback warned him of “severe consequences” if Maria did not stop playing squash. A newspaper photograph of President Pervez Musharraf conferring an award on her incensed the Taliban. As if to reiterate their point, the Taliban faked a security threat at her training facility. The academy, teeming with children, came first for Maria, who retreated into the confines of her home. Even though she continued training at home, it was not the same. Her game suffered and Maria slid into depression, even as officers worked to ensure that the Taliban did not harm her.

A sliver of hope arrived with the announcement that the 2010 National Games would be held just down the road from her house in Peshawar. Maria signed up excitedly, only to be turned away at the entrance on the D-day. “The one athlete the Taliban did not want in the stadium was the Pashtun girl, playing in shorts, bringing dishonour to her tribe,” she said.

As an aside, I mentioned the fatwa against Sania Mirza for playing tennis in short skirts, and Maria said: “Love for religion should come from within and stay there. My faith is between me and my God. I think the more we keep religion out of education, sports and politics, the better.”

When she appeared for a visa interview at the US consulate so she could play in the Delware State Open tournament, it appeared that the officer was going to deny her visa. Desperate, Maria slid him a CNN article titled, 'Teen Athlete fled Taliban Stronghold to Pursue Dream'. Not just her squash dreams but the safety of her life depended on it. The article clinched the visa for her and, although she lost in the first round, destiny was smiling on her again. Shortly after her loss, she heard from Power through a series of fortuitous events.

Cassandra Sanford-Rosenthal, documentary producer and filmmaker, heard about her from Power in 2012 and flew to Toronto to meet Maria where she was training. “By the end of that meeting, I was sure I wanted to produce a documentary about Maria,” said Cassandra.

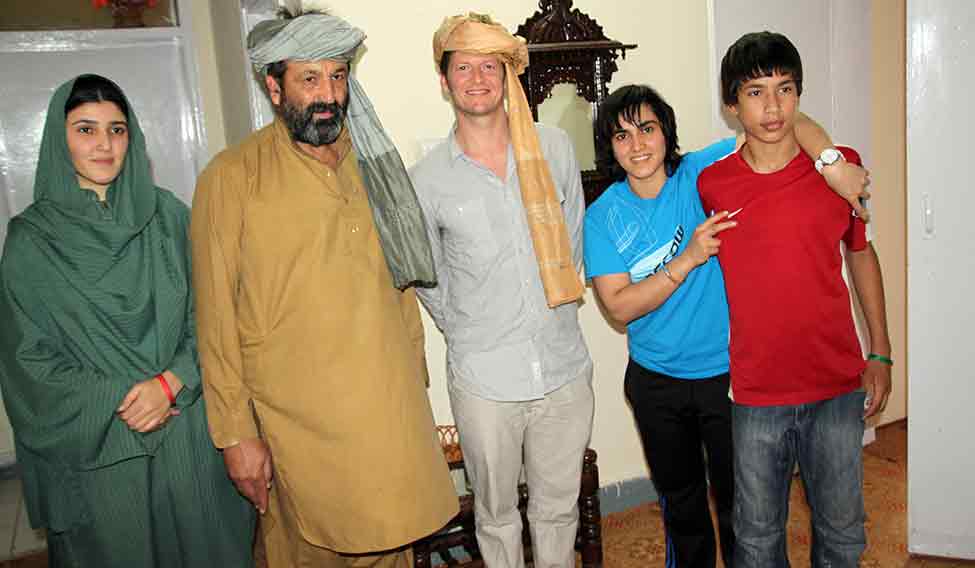

Support system: Maria with her family.

Support system: Maria with her family.

In 2013, Cassandra, along with director Erin Heidenreich, flew to Peshawar to meet Maria’s family, whom she described as “devout in faith, strong-willed and open-minded with immense gratitude in their hearts even for the negative experiences in life.” The duo followed Maria and filmed her in Seoul, Hong Kong, Toronto and New York, where she was participating in tournaments. Risking life and limb, Erin even ventured into the restive Federally Administered Tribal Areas, clad in the 'chador' worn by the local women, to film the documentary tentatively titled The War to Be Her.

“It is hard to say what a four-year-old or 12-year-old girl felt disguising herself as a boy here just to experience life,” said Erin. “Even so, I could fathom somewhat the frustration of being unable to move around freely, play with friends or even go to a store by yourself if you were a girl. We hope that Maria’s story will inspire and awaken the spirit of people across age, religion and gender divide.”

Under Power's world-class coaching, Maria has since regained her old game and confidence. He believes Maria “absolutely has the ability to be a winner.” In January 2012, she entered and won the Liberty Bell Open tournament in Philadelphia. Ranked 49th in the world, winning is everything to Maria, who says she is quick to erase memories of cities where she loses matches. Chennai, where she lost to Indian players Joshna Chinappa and Dipika Pallikal, therefore, isn’t a favourite. “But the matches where I lose after I put up a good fight, those I don’t mind,” she said, with a laugh.

She is worried about her family back home in Peshawar, where they live in the shadow of violence. She tries to keep the worries away by finding pleasure in small things in life, like “learning painting, reading books and watching documentaries, paying bills and navigating the world freely.” She runs squash camps for children when she goes back to Pakistan and is keen to use sport to effect positive social change. And she nurtures the ambition to be world number one, even as she waits to recover from acute plantar fasciitis, which affects the heels. “There’s no squashing that dream,” she said, resolutely.