Cut cloth pieces strewn on the floor add colour to Kavithamathi Jayamurthy’s monochrome life; the whirring sound of the two sewing machines helps drown the cacophony inside her head. Her smile, warm and welcoming, blinds you to her past, momentarily. Kavithamathi, clad in a faded maroon salwar suit, looks calm. But her life as a Sri Lankan living in Kilinochchi—the erstwhile bastion of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in the northern province—and later as a refugee in Tamil Nadu, India, was anything but that.

Six years after the ethnic war broke out in 1983, owing to tensions between the Sinhalese Buddhist majority and the Tamil minority, 7-year-old Kavithamathi left home with her parents and siblings for India. Her life as a refugee began at a camp in Ottanchathiram in Tamil Nadu, where she married Jayamurthy (now 42) and had two children. A year after the ceasefire in 2002, she returned with her husband and children, hoping the war would end soon. But it only got worse, and the family was forced to move to the Kathirkamam detention camp in Sri Lanka. When her mother asked her to return to the Ottanchathiram camp, she refused as she wanted to build a house on her property in Rathinapuram in Kilinochchi. It took her seven more years to return to Kilinochchi. She was finally home, years after living in exile, getting displaced in her own country, walking several miles with her family and boarding the army vehicle during war in search of a haven that turned out to be a hellhole.

Today, Kavithamathi, 40, and her sister Kayalvizhi, 37, stitch blouses and salwars, earning SLR15,000 a month. She now wants her mother and brother’s family, who have chosen to stay back in Tamil Nadu as refugees, to return. “My mother still sees Kilinochchi as the same old backward district with no electricity or medical facilities. My brother thinks his children will not get a good education here. But everything has changed,” says Kavithamathi. “I feel I have lived a thousand years away from my own Kilinochchi. I am totally relieved because I have come back to my homeland, even though it is difficult to make ends meet here.”

Such stories are quite common in the Tamil-dominated northern and eastern provinces of Sri Lanka. War split families in the island nation; exile untied many of them in India, in the 110 refugee camps across Tamil Nadu. When peace returned to the war-torn provinces, so did many of the refugees. A few families, haunted by their past and uncertain about the future, are still reluctant to return home.

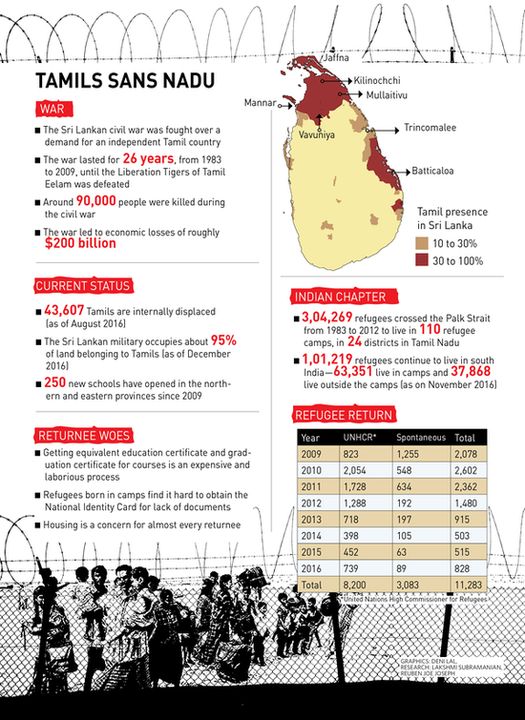

A year after the end of the nearly three-decade-long civil war in 2009, there were 1,46,098 refugees living in 64 countries, of whom at least 75,000 have returned to Sri Lanka between 2010 and 2016. Statistics from the Tamil Nadu refugee and rehabilitation department, the government of Sri Lanka, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and OfERR (Organisation for Eelam Refugees Rehabilitation) show that there were at least 8,200 voluntary returnees and 3,083 spontaneous returnees from Tamil Nadu between 2009 and 2016.

“It is a very positive trend. Our people are returning voluntarily,” says D.M. Swaminathan, Sri Lanka’s minister for rehabilitation and resettlement. “With the new government under President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, peace has returned to the northern and eastern provinces. We have released lands to the extent of 2,990 acres in Jaffna and 1,000 acres in Trincomalee only to make the internally displaced and the refugees get back to their homeland.”

Homecoming, however, has not been the happy ending to the suffering the returnees, perhaps, were hoping for. Kalyani Arunagirinathar, 36, along with her husband and two children, came back to her old, broken house in Deva Nagar in Trincomalee in October 2016. Kalyani’s black skirt and grey kurti is torn in places. She works as a domestic help, earning SLR4,500 a month. Her husband is physically challenged. “We thought we could resume a peaceful life after our return. There is peace. But I don’t know where to start life,” says Kalyani. “There is nothing—no money to build life. I cannot put my children in school as there is no financial support. For how long can I depend on the NGOs?” Her mother, Maheshwari Selvam, tells us how she walks miles to find a job as a farm labourer. “I will soon get a job as a labourer on a farm that is 15km from here,” she says.

According to a Sri Lankan government document, about 4,700 refugees have returned. At least 30 per cent of them are leading a peaceful life, if not a comfortable life. Most of them are fighting to get their land back or get loans under the government housing scheme or are struggling to find a job or to put their children in school.

A hopeful Velayutham Sreedharan, who left Mannar for India at the age of eight, returned with his family of four in 2015. “We decided to come back because our elder son died after he fell in a lake on the outskirts of Chennai,” says Velayutham. “We could not continue to live in the camp as his memories were haunting us. We thought we could raise our other two children well in Vavuniya. But it is a new struggle here every day.”

Velayutham, 38, now works on his brother-in-law’s farm, growing papaya, eggplant, groundnuts and tomato. “There is no water in our farmland. We can’t afford to dig a borewell,” says his wife, Suganthini, 38. She used to work as a supervisor in a soap manufacturing company in Chennai while living in the refugee camp. “It is hard to find a job here equal to what I was doing in Tamil Nadu,” says Suganthini, who did her graduation in commerce from a Chennai university. She and her two children help Velayutham on the farm on Sundays. He still has not managed to get the National Identity Card for his children who were born in the camp. Both his children, like those of other refugees, go to a Tamil-medium school.

Christa Shiromi Arulnayagam, 29, who lives in Kalubowila in Colombo, had no option but to put her nine-year-old daughter, K. Krishika, in a Tamil-medium school because she couldn’t afford to send her to an English-medium school and also because the syllabus in schools here is different from what is taught in the schools in Tamil Nadu. “The Tamil words used in Sri Lanka are different from the ones my daughter learnt in the school in Tamil Nadu,” says Christa, a nurse.

Jasmine, 15, would agree. Born and raised in a refugee camp in Erode, she was made fun of by her friends and teachers in her school near Kopay, Jaffna—the capital of the northern province—for not knowing too many Sri Lankan Tamil words. “She wrote kaezhel varagu, which is the Indian Tamil word for finger millet instead of the Sri Lankan word kurakkan. The teachers complained that my daughter doesn’t know Tamil and that she is not fit to be promoted to the advanced level,” says Jasmine’s mother, Kamala Rani, 50. So, she has arranged special tuitions for Jasmine, who wants to be a doctor. But it will be an uphill task for Kamala Rani to fulfil her daughter’s dreams. Her husband, Sivaganesan Ganapathipillai, 52, is physically challenged. And, she is now trying to build a home, for which she had to mortgage her bangles for SLR50,000 and take a friendly loan of SLR3 lakh. She has received SLR7.44 lakh under the government housing scheme. “It was not enough as we made little modifications in the construction plan.... My debts are now more than my earnings,” she says.

The government housing scheme has benefited not just the refugees but even internally displaced people in Sri Lanka. According to figures shared by the rehabilitation and resettlement department of Sri Lanka, SLR14,000 million was allocated for the resettlement programme and SLR8,634 million for housing projects in the eleven districts of the northern and eastern provinces.

But some like Muthaiah Velayuthapillai from Paranthan in Mullaitivu district haven’t received any help from the government under the housing scheme despite several applications. Nor could he get his land in Viswamedu back. The 65-year-old man, therefore, bought five acres for SLR5 lakh, a part of which he raised by selling his wife’s jewellery, but most of it came from his earnings as a milkman during the 23 years he spent as a refugee at the Uchapatti camp near Madurai. Today, he lives alone in a one-room house, surrounded by a lush paddy field. His wife lives with their two sons in Colombo. His elder son is a taxi driver, and his younger son works for a CCTV company.

Another problem plaguing the returnees is the lack of jobs. Take, for instance, Rajmohan Abdul Gani, 28, who did his MPhil in microbiology from Bharathidasan University in Tiruchirapalli. He, along with his mother and sister, fled to India in 1990 after his father, Abdul Gani, who was in the LTTE, was killed. He returned in 2014, whereas his mother, Suseela, and sister, Rajivi, stayed back at the Pudukottai Thoppukollai camp. He hasn’t found a job yet because his degree is not recognised in Sri Lanka, he says. Though Jaffna University opened a department of microbiology, he says it preferred Sri Lankan graduates for appointment as lecturers. He is now an office clerk in an organisation that works among refugee returnees. Dejected, he says he will go back to India soon.

But Ramya Armugam, 26, and her sister, Akhilaveni, 28, were fortunate. Ramya, who did her MBA from Bharathiar University in Tamil Nadu, is an accountant, and Akhilaveni a midwife in Vavuniya. Their elder brother, Keerthiswaran, 34, is a painter. But fortune didn’t always favour them. As with most Sri Lankan refugees, a boat is central to their story. Their parents, Armugam and Shanmugeswari, had taken an illegal boat from Mannar to Rameswaram in 1987, but went back with their two children to Vavuniya in 1990 after spending three years at the Mylambadi camp near Erode. Within months, they were back on an illegal boat to Rameswaram. This time, Shanmugeswari was pregnant with her third child.

In 1997, Armugam took a boat from Rameswaram to Thalaimannar to check on the situation back home. But the boat reportedly capsized. Shanmugeswari went looking for her husband, but to no avail. She returned to the camp, broken-hearted. She soon started selling dress materials at the camp to take care of her children. Still, she couldn’t fund her children’s education. Keerthiswaran dropped out of school, and Akhilaveni was sent back to Sri Lanka in 2004, where Shanmugeswari’s parents and sister looked after her. The family finally returned to Sri Lanka in 2014 after Ramya completed her MBA.

Like Shanmugeswari, Vasanthakumar Janardhini, 34, didn’t let circumstances dictate her life. Today, her tailor shop in Vavuniya is the busiest, and she also gives classes for women like her. She is all smiles when we meet her. “Being a Sri Lankan Tamil is to learn to live life happily as it comes,” she says. She has learnt this the hard way. Her family of three returned to Sri Lanka in 2012. But soon, her husband died of snakebite. Her brother, Shanmuganathan Sudarsan, 38, was arrested and allegedly tortured in a detention camp for four years by the Sri Lankan army. He was picked up along with his wife, Sivaroobini, and his one- and-a-half-year-old son, Sarujan, from a lodge in Colombo in 2008. “We were getting our passports ready to leave Sri Lanka. My wife and son were let off in six months. But I was in the Boosa camp for four years,” recalls Sudarsan, who now runs a travel company.

The scars of the war continue to haunt K. Sooryan (name changed), 40, too. A LTTE soldier from the age of 14, he worked as a medical assistant, treating wounded LTTE men. In 1995, he worked in the Vanni forest, and in 1996 left the LTTE to live with his parents. But in 1997, he was back with them. In an army attack in Paranthan, he lost his left leg and his hearing in the left ear. “I got treated and came back from the LTTE to live with my family again. But, in 2004, when the Tigers wanted one person from each family, I decided to go only to safeguard my three siblings,” says Sooryan. After the war, he managed to get into a camp for the internally displaced people, and from there fled the country by pooling in SLR3 lakh. He was treated for his injuries at the government hospitals in Madurai and Dindigul. He returned in 2010, but was detained at the airport. “I was taken to the Boosa detention camp in Galle,” he says. In October 2016, he was released from another camp following severe protests. He does odd jobs at construction sites, whereas his wife, Sivadevi, 38, is a midwife at a hospital in Vavuniya. All he wants now is a peaceful life with his wife and two sons.

Peace, after all, was what brought many refugees home. But will it make them stay?

Kavithamathi Jayamurthy—Rathinapuram, Kilinochchi

Being the bastion of the LTTE, Kilinochchi was a killing field. So, Kavithamathi, with her parents and siblings, left for India in 1989. She grew up in a camp, got married and had children, too. A year after the ceasefire in 2002, she returned to Kilinochchi with her husband and two daughters. But soon the war began again, and they shifted to a detention camp in Sri Lanka. The harsh camp life didn’t dull her spirits. She put her tailoring knowledge to use, and saved SLR80,000. When she returned home in 2010, she used some of the money to buy a sewing machine and opened a shop. The rest of the money was spent on making her farmland cultivable. Now all she wants is her mother and brother, who are still in India, to return.

(From left) Santharooban Rajaratnam, his sister, Santhakumari, mother, Selvarani, sister-in-law, Darsana, and brother, Nisanthan—in Dharmapuram, Kilinochchi

Her husband left her in 1996; she left her country. With three young children to look after, the unrest in Kilinochchi was too much to take for Rajaratnam Selvarani. She left for Tamil Nadu along with her mother and children—a mentally challenged daughter, Santhakumari, and two sons, Santharooban and Nisanthan. After six years at the Pudukottai camp, she came back home in 2012. The 46-year-old is now busy building a house on her mother’s farmland with the SLR8 lakh she received from the government under the housing scheme.

Kalyani Arunagirinathar with her daughters, Dhilakshana and Vidushana—in Trincomalee

Kalyani and her family, including her mother, husband and two daughters, now aged 12 and 5, fled their home in Trincomalee in 2006 when the army came knocking on their door, looking for LTTE members. They say they were tortured at gunpoint. They lived at the Mandapam camp for a while and then shifted to Paruvai camp in Tiruppur in Tamil Nadu.

They returned home in 2016. Kalyani, 36, now works as a domestic help and her husband is physically challenged.

Velayutham Sreedharan with wife, Suganthini, son, Dhilakshan, and daughter, Sruthika—in Thavasikulam, Vavuniya

Sreedharan was eight when his parents left Mannar for India. He met his wife, Suganthini, at the Gummidipoondi camp near Chennai. Sreedharan worked as a painter and his wife was a supervisor in a soap manufacturing factory in Chennai. They returned to Sri Lanka in 2015 when their elder son died after falling into a lake in Chennai. Today, their son, Dhilakshan, 13, and daughter, Sruthika, 5, study in a nearby school in Vavuniya. Sreedharan, 38, grows peanuts and papaya on his brother-in-law’s farm.

Shanmuganathan Sudarsan with sister, Vasanthakumar Janardhini—in Vavuniya

Sudarsan, 38, was a refugee in India for 14 years, from 1990 to 2004. On his return home, he tried to start life afresh but the war broke out again. He, along with his wife, Sivaroobini, and one-and-a-half-year-old son, Sarujan, tried to leave the country in 2008, but were picked up by the army from a lodge in Colombo while getting their passports ready. They were kept at the Boosa detention camp in Galle. While his wife and son were let off in six months, he says he was tortured for four years. Around the time of his release in 2012, his sister Vasanthakumar Janardhini, now 34, returned to Sri Lanka with her daughter Lavanya, now 16. After her husband died of snakebite, she started her tailoring shop, where she also gives sewing lessons. Sudarsan now has his own travel business.

Kamaleswari Udhayakumar with father, Ramasamy—in Mullaitivu

Kamaleswari became a refugee in India at the age of seven. She left her birthplace, Mannar, in 1990 with her parents. The Bhavani Sagar camp became home, where she also met her husband, Udhayakumar. Her children, Vinodha and Dinesh, too, were born there. The family returned to Udhayakumar’s native Mullaitivu in 2003. But their home was washed away in the 2004 tsunami. They then lived in a temporary shelter. But the war broke out again, and they came back to the Bhavani Sagar camp in 2008. They returned to Sri Lanka in 2010. But before they could settle down, Udhayakumar reportedly died when he took an illegal boat from Batticaloa to Australia to find a job. Kamaleswari went looking for him, but in vain. Now the 34-year-old has a poultry farm at her tsunami shelter. Her father, Ramasamy, 59, lost his eyesight while working for a granite quarry in Tamil Nadu.

Sivaganesan Ganapathipillai with wife, Kamala Rani, and daughter, Jasmine—in Kopay, Jaffna

In 1992, Sivaganesan, now 52, and Kamala Rani, now 50, left Sri Lanka for India, where their daughter, Jasmine, was born. When the war ended, so did their exile. But home is still a faraway dream. Kamala Rani is busy building a house, thanks to the SLR7.44 lakh she received under the housing scheme. But she also had to pledge her gold bangles and take a friendly loan of SLR3lakh. She is the sole breadwinner in the family as Sivaganesan is differently-abled. Everything is expensive here, she says.