Five interlocking rings have defined the Olympic Games throughout a century as a symbol of sport uniting the world. The design was drawn up by Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the French aristocrat, who rekindled the flame of the ancient games of Olympia, Greece, in 1896. And, through his idealism, those rings represent five continents as he saw them—blue for Africa, yellow for the Americas, black for Asia, green for Europe and red for Oceania.

One wonders how Coubertin might recoil from what has become of his brainchild. The Games due for Rio de Janeiro from August 5 to 21 are bigger than anything he might have imagined: 10,500 competitors, 306 events, 206 countries, 28 sports. And yes, they go “Citius, Altius, Fortius” (Faster, Stronger, Higher), in the words of the Olympic motto. But so does the money, and so does the corruption.

It is still, for some of us, a far, far better way to celebrate human competitiveness than the alternative, which usually leads to war. But if we watch over the three weeks, can we trust what our eyes and the scoreboards tell us?

Begging the baron’s pardon, we might adapt his rings this way:

Blue: Who is the most famous athlete in these Games? Neymar Junior, the footballer, is competing. So is Usain Bolt, the fastest sprinter of all time.

Neymar would perhaps turn more head than Bolt in Mumbai or Mombasa. But Bolt is more of an Olympian by any measure you view it. The Jamaican’s events, the 100 and 200 metres, have been blue ribband races ever since the Games were devised. Football is an imposter at the Olympics—a team game where the best in the business rarely show up because FIFA wants to keep the best of its sport and the gargantuan (and proven corrupted) profits for itself.

A runner in a costume depicting the Rio 2016 Olympic torch decorated with a figure of Usain Bolt at a race in Sao Paulo in Brazil | Reuters

A runner in a costume depicting the Rio 2016 Olympic torch decorated with a figure of Usain Bolt at a race in Sao Paulo in Brazil | Reuters

So soccer sends to the Olympics often secondary players, though by agreement with the International Olympic Committee, the stipulation that the participants are mainly under 23 years of age does satisfy another long held tenet of the Games, the appeal to youth. Neymar, however, is 24, and is counted as one of three over-age players each of the 16 teams is permitted.

Neymar opted to play in the Olympics; Lionel Messi, his club mate at Barcelona, chose instead the Copa America Centenario tournament in the US in June. Messi failed to lead his country to the trophy, and quit Argentina’s national selection as a result.

But Messi did influence Neymar by telling him that staying in the Olympic Village, socialising with elite athletes from right across the spectrum of sports, is a unique experience beyond football’s singular domain.

Neymar, moreover, is driven to try to put right two things. He suffered a back injury during the 2014 World Cup in Brazil; and without him Brazil imploded. And for all its history, for all the marvel that was Pelé, and for all that men like Bebeto and Romario tried, the one thing that Brazil has never won at football remains the Olympics.

So Neymar is shooting for fame. Bolt is doing the same thing, but on his own terms. The big Jamaican, now 29, is attempting to be the first runner to win the triple-triple—the 100m, 200m and 4x100m relay—all of them, at three consecutive Olympiads.

To do it, Bolt has to be the saviour of track and field. His events are contaminated. He calls the doping violations that have destroyed athletics “a sideshow” and says he is focused on winning. Fair enough: If he is clean—and every test that is made on his blood has come back clean—then this huge, amiable, lyrical Caribbean is entitled to strive for what he believes would put him on a par with legends he looks up to: Muhammad Ali, Pelé and Michael Jordan.

A demonstrator is taken away by riot police during a protest against the money spent on Rio Olympics | AP

A demonstrator is taken away by riot police during a protest against the money spent on Rio Olympics | AP

By his own reckoning, Bolt is two thirds of the way there. He won the 100m and 200m at both the Beijing and London Games in 2008 and 2012.

He anchored the relay sprints to gold in those as well. The blot on Bolt’s horizon is that the 4x100m gold in Beijing is likely to be annulled because his fellow Jamaican Nesta Carter was recently found to have failed a dope test that was stored in a laboratory since 2008. This retrospective re-examination, using analysis that was unavailable then, could strip Bolt of his relay medal.

“What can I do?” Bolt asked in London recently. “Rules are rules. But everybody knows it is going to still stand because I’ve shown over the years that I’m the greatest athlete, and that’s the key thing.”

Sorry, Usain. The key is being seen to be clean. And with all this re-examination of samples, and with the whistle blowing now coming out of Russia, what appears to have been clean yesteryear can be condemned tomorrow.

Bolt himself is from a nation where drug testing leaves something to be desired. And while Bolt stands indisputably on the top of the podium, the next five fastest humans have all failed dope tests. They are: Tyson Gay (USA), Yohan Blake (Jamaica), Asafa Powell (Jamaica), Justin Gatlin (USA) and Nesta Carter (Jamaica).

Thrill us if you will, Mr Bolt. But please, please, be pure.

Performers entertain Olympic delegations during a welcome ceremony at the Olympic athletes village in Rio de Janeiro | AP

Performers entertain Olympic delegations during a welcome ceremony at the Olympic athletes village in Rio de Janeiro | AP

Yellow: The second ring reflects our changing world. Heaven knows, these Olympics need something inspirational, and I imagine that Coubertin’s soul would be uplifted by the IOC’s decision to add an extra team to those taking part.

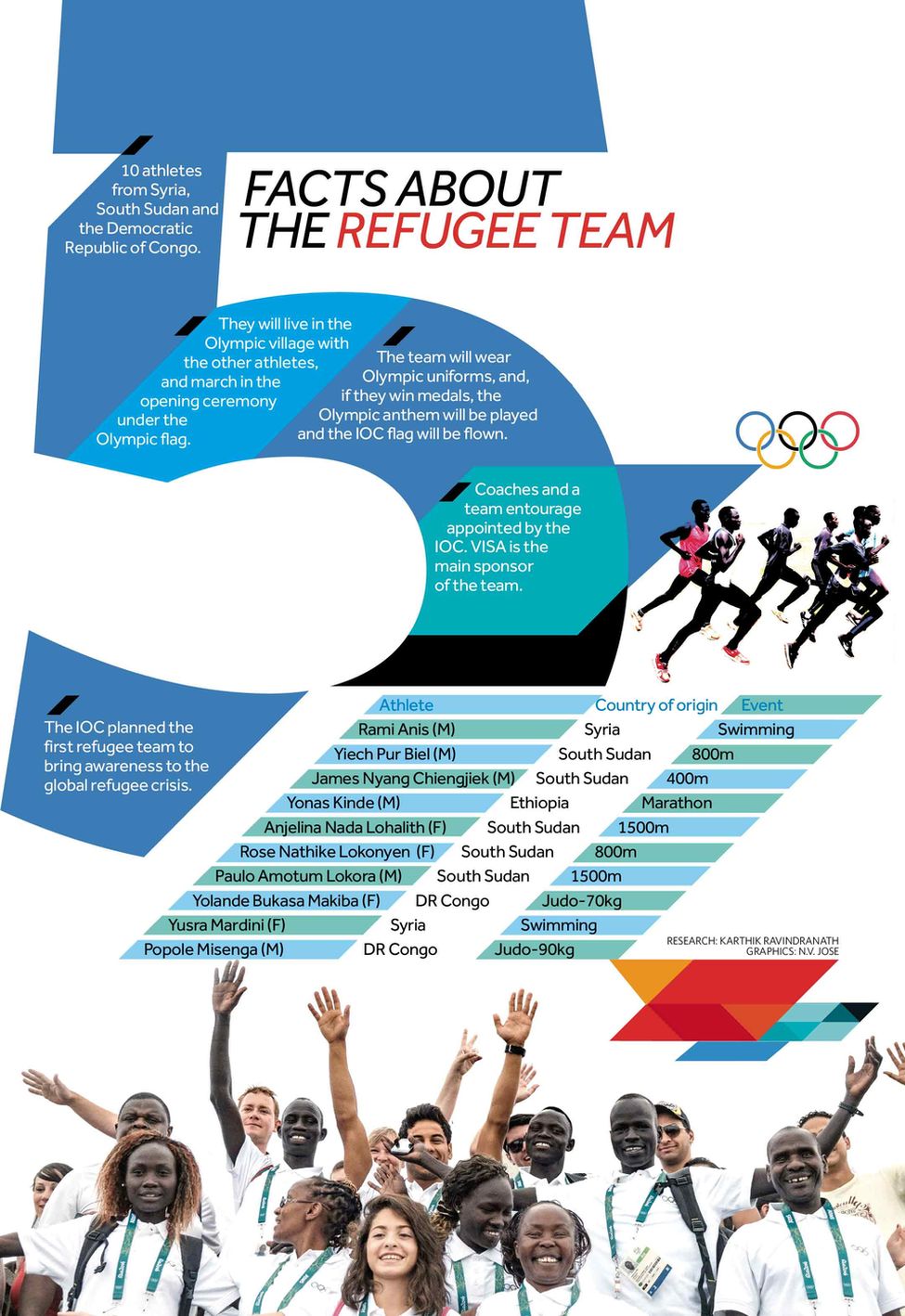

Rather than turn a blind eye to the refugee crises that engulfs theworld, the Committee voted in March to spend two million dollars on a gesture of hope. The money funds a team of 10 athletes, identified by the United Nations Refugee Agency, to join in these Games.

The “Refugee Olympic Team” (or ROT) will enter the stadium just before the host nation, Brazil, at the back of the opening ceremony. They will march behind the Olympic flag. And they, survivors of some desperate escapes from wars in Syria, South Sudan and Democratic Republic of Congo, will undoubtedly receive the mother of all receptions.

They should, because the stories of how Rami Anis and Yusra Mardini from Syria separately reached their new homes in Belgium and Germany is heroic testimony to human spirit way beyond anything they strive for in the Olympic pool. Likewise the travails of Pople Misenga and Yolanda Mabika who fled from the Congolese civil war and are now judo players in their adopted homeland of Brazil.

Never was the saying “it is not the winning but the taking part” truer than in the case of these 10 refugee Olympians.

Every individual story of the tidal wave of displaced human beings tugs at our hearts. Thomas Bach, the troubled IOC president whose leadership is questioned over the drugs issue, made the right statement when he said that the IOC was touched by the magnitude of the refugee crises and wanted to send a message of hope to all refugees in the world.

Message received and understood. The journey of Mardini, from Damascus to Berlin, already makes her a winner.

Last August, Yusra and her older sister Sarah were among some 24 people crowded into an inflatable dinghy that should have carried a maximum of seven people.

They left Izmir on the Turkish coast, but the boat’s motor failed on the high sea. The vessel took on water. Yusra and Sarah, daughters of a swimming instructor, jumped into the water and for three hours pushed and kicked the boat and its human cargo to the safety of the Greek islands.

Mardini now swims at her local club in Berlin, training in a pool built for the 1936 Olympics, where Adolf Hitler had designs on using the Games to promote his theory on white Aryan supremacy.

She is one of millions of refugees for whom the first race, survival, is already run.

Black: This is the darkest circle, the devaluation of the Olympic ethos by the collusion between athletes prepared to cheat, doctors and pharmacists prepared to collude with them, and now, for the second time in history, the state collaboration in drugging men and women, boys and girls, to win medals that their country somehow imagines enhances the state in the eyes of the world.

Drugging athletes, often from the cradle and possibly without some even realising they are being doped, has become a cold war issue.

It has been for most of our lifetime. Communist East Germany (the GDR) was either the most remarkable small-state phenomenon of sports 50 years ago or, as later proven, the most repulsive state ruination of childhood through injecting kids that the world has known.

How a nation of 15 million could beat everyone so consistently across so many disciplines was suspect at the time. And laid bare once the Berlin Wall fell and the infamous Stasi files were opened.

So if Russia, with 145 million population, is now the new GDR in terms of mass manipulation of sporting achievement, is anyone surprised?

At the time of East Germany, my question was that if this was the state basking in ill-gotten glory, was it so much worse than the west where parents push children, or where coaches seek reflected glory, or huge commercial companies back the programmes that produce winners? Programmes which harm the child (countless numbers of whom fall, broken, by the wayside).

Programmes driven for profit.

Programmes in which popping pills or taking injections is not seen as the biggest crime. The biggest crime is getting caught.

The accusations against Russia warrant exclusion. My unease is that those driving the investigations, and the courts, come predominantly from the opposing ideology and politics.

But you have doubtless read more than enough on both sides of the doping divide. Draw your own conclusions.

Green: Another ring, another opportunity to be thankful of those champions we do feel we owe admiration. Think of Jesse Owens, the great runner and jumper who, as a black American, confounded Hitler’s propaganda attempt to prove the “supremacy” of white athletes.

Think of Irena Szewińska, born in St Petersburg, Russia, but raised in her father’s home city, Warsaw in Poland—who won six Olympic medals (three of them gold) over 100, 200 and 400 metres and long jump while holding down a job as a leading economist and rearing two sons.

And think Al Oerter, an American I got to know personally, who was supremely modest, and unbeaten in the Olympic discus arena where he won gold in Melbourne 1956, Rome 1960, Tokyo 1964 and Mexico City 1968. In the meantime, rather like Szewińska, he reverted to “real life” as a data processing manager. To Oerter the Olympics were almost mystical. He never entered the Games as world record holder, yet he summoned his own Olympic spirit whenever he entered those rings.

For him, and for England’s Steve Redgrave, the Olympics was a way of life. Sir Steven Redgrave won five consecutive golds at rowing between 1984 and 2000. Oerter suffered from high blood pressure, Redgrave overcame dyslexia. Both found their meaning as Olympians.

Red: The red warning light to the Games. Whither now the credo espoused by Coubertin? He was, of course, a blue blooded baron who could afford high idealism but he could never have foreseen our time in which television and sponsorship would turn his Olympics into a monstrous cash cow.

TV everywhere pays for the Games, particularly in the US where NBC agreed to pay USD 4.38 billion to broadcast the Games between 2014 and 2020—and will pay $7.65 billion from 2021 to 2032.

The piper calls the tune, and today we have golf in the Games even if some leading golfers, like Northern Ireland’s Rory Mcllroy make it plain that they do not regard their game as an Olympic sport and decline to take part.

“Most athletes dream of competing at the Olympics,” Mcllroy said. “We [golfers] dream of Claret Jugs and Green Jackets.”

The Claret Jug has been awarded at the British Open since 1860, and the green jacket at the Masters since 1949. But the only time that golf featured at the Games during Coubertin’s time—in St Louis, America in 1904—he did not attend.

“The important thing in life is not the triumph but the struggle,” Coubertin said. “The essential thing is not to have conquered but to have fought well.”

He died in 1937. We can only guess what he would have made of men and women distorting the circles through state aided prohibited substances.