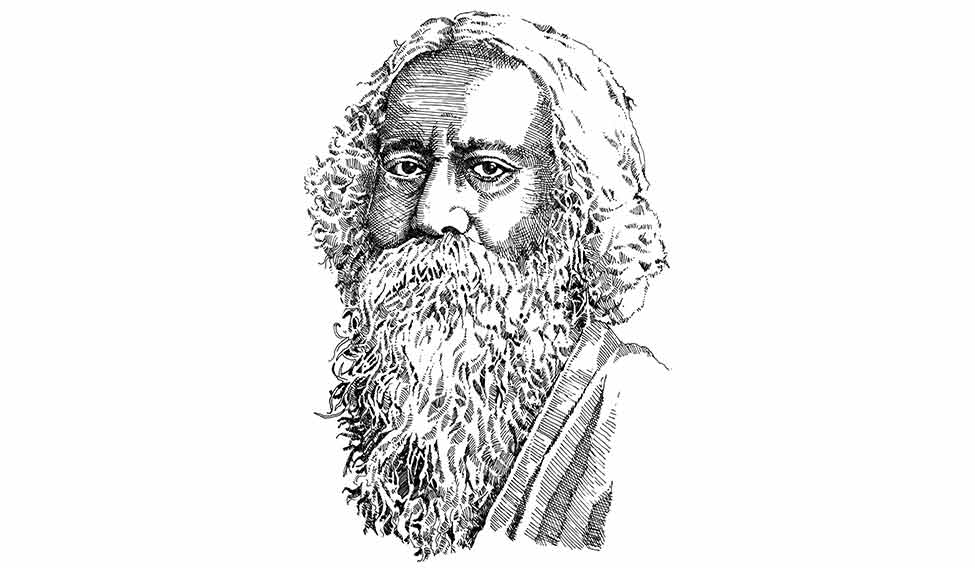

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high.... Where words come out from the depth of truth”. Everyone who has read Rabindranath Tagore in any language associates these words with him. Tagore has put the essence of whole human existence into these few lines of Gitanjali. People have often harked back to these lines. Pakistani economist Mahbub ul Haq quoted them in his Human Development Report, South Asia of 1997. Deve Gowda quoted them in Parliament when he was forced to resign as prime minister. And, so on and so forth.

But, this country is yet to realise these words and be true to them. Does any country seem to be trying? When Tagore sets up such a goal, clearly outlined, it’s your turn to decide whether you take up the challenge.

Yes, Tagore was a poet, painter, singer, composer, playwright, actor and writer. Yet, he concerned himself deeply with the human destiny of his country and the world. He consistently asked the question—what is it that defines a human being? It is not caste, creed, sex, language or country, it’s just being born as a member of the human race. To Tagore, all human beings share the same ‘holy’ brand of existence—humanity.

What, again, defines a nation? Is it its geographical borders which politicians playfully keep on shifting all the time? The India in which Tagore wrote is now trifurcated into three major countries. In the early days of our political struggle, Tagore didn’t like words becoming more important than human beings, than the suffering millions of the country. The ideals of Bharat Mata and Bharat Lakshmi, he said, were all wrong. Bharat Mata wasn’t someone playing the veena in the Himalayas. She, instead, was the mother who lived in her hut in a decayed village and didn’t know what to feed her malaria-stricken child day after day. Bharat Lakshmi was no bark-clad damsel who watered plants in the hermitages of Vashishtha or Vishvamitra. She was, rather, the one who, famished or half-fed herself, cooked in a rich man’s house to put her son in an English school so that he could become a government clerk one day. For Tagore, the “patriotism” of doling out dreams was a delusion cooked up by politicians. Not many people listened to him then, or now.

His patriotism was not of the type that said “my country, right or wrong, is the best country in the world!” He knew that such gloating might lead, and had often led, a country to imperialism. He condemned the plunder of Africa by western powers, as he almost cursed Japan for its aggression towards China. He wrote back to the poet Yone Noguchi, who had sought Tagore’s support for Japan’s Asian designs, saying, “I wish your people, whom I love, not victory, but remorse.”

Was he a mystic poet? Did he talk about a God all the time? Well, he wasn’t and he didn’t. Tagore was a poet of humanity and of this world. As a poet of India, he looked at it as the receptacle of “a great ocean of humanity”, composed of all—Aryans, non-Aryans, the Sakas, the Huns, the Pathans and Mughals. Everyone had mingled with one another to form one single body of people. Is India yet ready to listen to Tagore intently? Is any country?

One of his deeper human concerns was his passion for the preservation of nature. Nature not only was to be enjoyed or exploited, but had to be cherished for human survival. It was he who initiated vana mahotsava as a ritual at his Santiniketan school. Here is a poet and a human being with profound human concerns. We can stop listening to him only at our own peril.

Pabitra Sarkar was vice chancellor of Rabindra Bharati University.

Subramania Bharati

In the pioneer's penumbra

By A.R. Venkatachalapathy

Modernity came to India under colonial aegis. Under the impact of far-reaching social transformations, most Indian languages underwent profound change. This threw up fascinating literary figures who have become icons. Few of them, however, have contemporary relevance. Subramania Bharati (1882–1921) is exceptional, an abiding influence on modern writing in Tamil.

Bharati’s life was all too brief. Comparison with Tagore is inevitable. Bharati was born more than 20 years after Tagore and predeceased him by another 20. Of his 39 years, ten were spent in exile in the French enclave of Puducherry. A child of the Swadeshi movement, he was its perceptive chronicler and commentator, though not a critic like Tagore.

The poet began his career as a journalist. First as subeditor of Tamil’s then only daily, and later as the editor of a women’s magazine. For his writings as the editor of a “seditious” weekly, he had to flee British India. He was the first to publish political cartoons in the vernacular, and his journalistic prose was both informed and incisive.

But Bharati was essentially a literary man—a poet of inspired genius. His early poems, written in the thick of anti-colonial agitations, demonstrated the potential of language for political mobilisation. In his later poems, written in exile, we find a more reflective poet contending with the larger questions of life.

Bharati wrote stories. Though they do not conform to the grammar of the short story or the novel, they were not failures. Humour, an unknown commodity to Tamil literature, was his forte. He was also the pioneer of the autobiographical form in Tamil. Bharati touched nothing that he did not adorn.

Bharati is not history. In fact, Tamil writing, nearly a century after his death, continues to flourish in the penumbra of Bharati.

Venkatachalapathy is a historian and Tamil writer.