In the early 1980s, Satyajit Ray was speaking at a memorial event for a renowned novelist at Kolkata’s Academy of Fine Arts. During his speech, he said that contemporary novels were not fit enough to be converted into films as they lacked proper narration. “Many writers seem more inclined to use their minds rather than their eyes and ears,” he commented. “There is a marked tendency to avoid concrete observation. The writers are either incapable of or disinclined to visualise beyond certain points. This itself need not be held against a novel, but in a film writer, this tendency can only lead to a film that shows a lot but says very little.”

Ray added that there was a lack of adventure; everyone played safe. This led to “stagnation” in the literary world, he said.

Reading his comments in the newspaper the next day, Buddhadeb Guha, one of the popular novelists of the time, reacted sharply: “It is not the responsibility of writers to fulfil the needs of film directors.”

In his response, Ray brought up the way Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, in his novel Pather Panchali, described the style of how an old woman wears a sari. “He did not think of the film while doing that.... Today, such descriptions are missing from the literary world of Bengal,” he wrote in a letter to Guha.

Ray was echoing the thoughts of his friend, the writer Nirad C. Chaudhuri. His books, especially Atmaghati Bangali (Suicidal Bengali), spoke of the decay in Bengal, which had arguably formed the cultural and spiritual backbone of India in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Ray’s observation was prophetic. Over the years, Bengali filmmakers had been heavily inspired by literature. But, in the past few decades, Bengali literature has declined. And so has the cinema.

The Bengali film movement had started in the 1950s, when Ray, along with film critic Chidananda Dasgupta, founded the Calcutta Film Society. Those days, film was spreading throughout a newly born India, and theatre played a role in the wave. In fact, some filmmakers argue that the film movement was merely an extension of the theatre movement born in 1940s Kolkata.

But Ray was not part of this. Though his peers Ritwik Ghatak and Mrinal Sen came from the theatre movement, Ray started making films based on the classics he had read. He did, however, need actors for his films, and had to cast from the growing theatre scene.

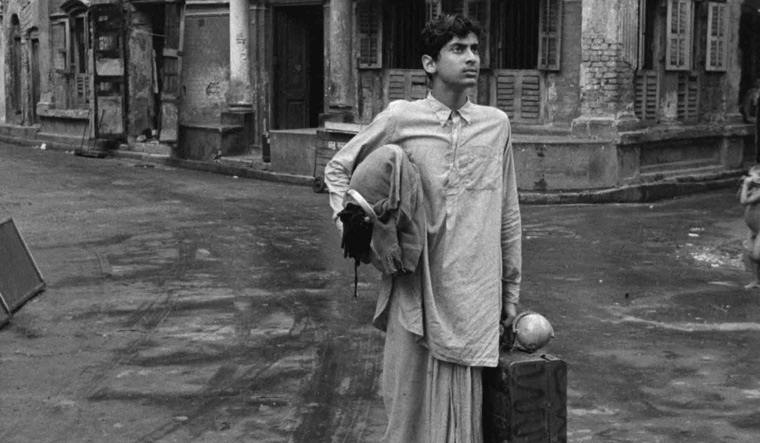

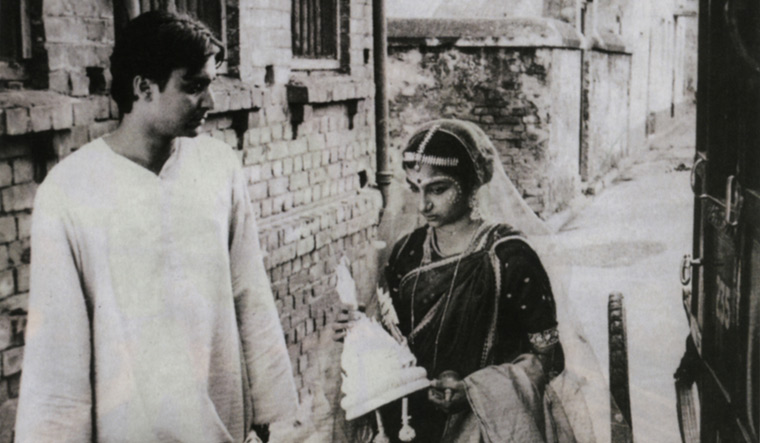

The reliance on literature saw Ray carving out three masterpieces—Pather Panchali, Aparajito and Apur Sansar—from a single novel: Bandyopadhyay’s Pather Panchali. His first outside of the Apu trilogy was a horrific satire made from Rajshekhar Basu’s short story Parash Pathar.

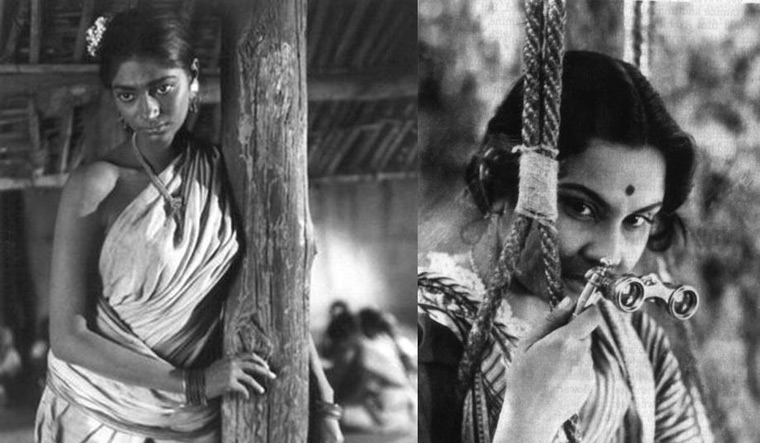

Though he relied on books, Ray would often elevate the words with his lens. In Pather Panchali, there is a famous scene where siblings Apu and Durga rush to watch a running train, a first in their lives. They find the speeding behemoth magical, overwhelming even, and the camera lingers. The novel had no such expression.

“I often asked Manik da how he could make such great scripts out of big novels,” director Adoor Gopalakrishnan told THE WEEK. “He told me, ‘No, Adoor, they are all in the books’. Look at the magnanimity of the man. Anyone else would have taken credit for making such artistic changes in the movie.”

Throughout his career, Ray had encounters with writers about the changes he made to their words. While senior writers like Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay and Sunil Gangopadhyay were displeased about Ray meddling with their stories, no writer ever withdrew the rights they had given to Ray.

Ray’s adaptation of classics influenced other filmmakers, too. While Tapan Sinha crafted a fine film from Rabindranath Tagore’s Kabuliwala, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s novels, like Devdas, too, found their way into film. Of course, there was a gulf in class between Ray and the commercial directors, but the overall introduction of Bengali literature into cinema enriched the industry. The inverse was true, too—the films helped take Bengali literature to the world. Even Tagore’s Nastanirh became more popular after Ray made Charulata in 1964.

Ray’s art house roots did not preclude commercial success, either. Pather Panchali was the first Indian film to earn 010 crore. Many Bengali films, in fact, broke Indian collection records and Kolkata dominated the cultural scene in the country in the 1950s and 1960s. Ray put Indian cinema on the world map and some of his films were as popular in places like Paris as in Kolkata. In every decade since the making of Pather Panchali, at least seven or eight cult movies were born in Kolkata. The golden era seemed to be unending.

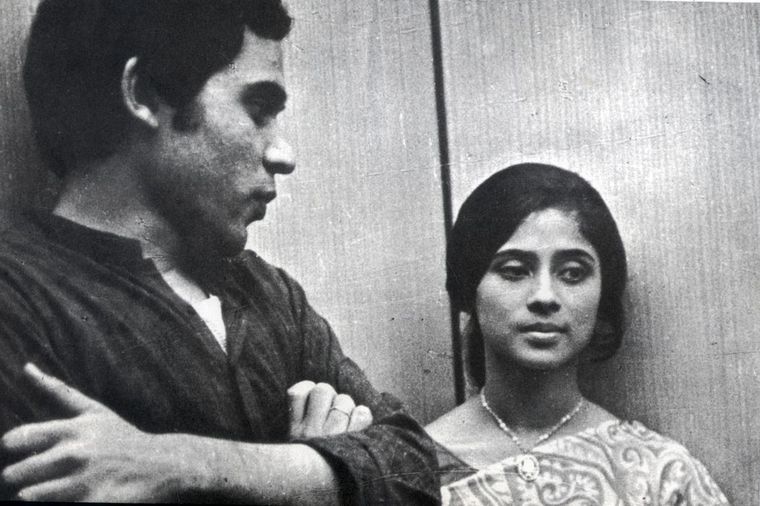

Then came strife. The happenings in a de-Stalinised Russia, the Vietnam war and Mao Zedong’s rule in China started moving a section of Bengal’s youth. The Naxalbari uprising happened in 1967 and there was a subsequent upheaval in Bengal. It was a political time, and a lot of people wanted to see that reflected on screen. Ray was arguably subtle with his politics in film; he was also criticised for not taking on contemporary issues. Some of his detractors said Ray’s films showed a “fake Bengali renaissance”. Around this time, Mrinal Sen—who was more in-your-face with his politics—gained popularity. His 1969 Hindi film Bhuvan Shome became a cult classic, and he was dubbed the father of the ‘New Wave’ of Indian cinema.

Sen, who had till then mastered commercial cinema, became a filmmaker whose offerings had arguably more appeal across India than those of Ray’s film society movement. Soon, the film scene was populated by filmmakers who were hungry for a new aesthetic; these included eventual stalwarts liked Gopalakrishnan, Shyam Benegal, Kumar Shahani and Girish Kasaravalli.

Though initially unnerved by this challenge, Ray soon responded with some of the best urban-centric movies divorced from the Bengali classics. He, however, did it on his own terms. He retained his style of filmmaking, and injected it with politics. His Calcutta Trilogy—Pratidwandi, Seemabaddha and Jana Aranya—was far more socio-political and perhaps influenced the young Kolkata more than Sen’s own trilogy: Interview, Calcutta 71 and Padatik.

Also read

- ‘Pather Panchali’ was 1st genuine cinema to come out of India: Adoor Gopalakrishnan

- The Bengali film industry has become bankrupt, says Goutam Ghose

- Not all of Satyajit Ray's films are equally great, says Girish Kasaravalli

- My father kept politics in the background in his movies, says Sandip Ray

- Losing the plot

- Flop show

According to one critic, though, Ray was in some measure inspired by Sen. “Ray used freeze shots, negative shots and back and forth shots, like Sen used to do in his urban movies,” he said. “While Sen was greatly influenced by Ray in the 1960s, in the 1970s it was Ray doing a Sen.”

Said noted film critic Vidyarthy Chatterjee: “In a sense, Ray was provoked and pressurised by the student movement into making contemporary films. The 1960s saw the industrialised Bengali middle class having more money in their hands. So, the middle class had the voice to demand what they wanted.”

This was also the time when Ritwik Ghatak, another stalwart of the era, was making his films on the themes of social reality and partition. Ghatak, however, only became popular after his death in 1976. “He got a raw deal as none of his films were preserved well,” said Ashoke Viswanathan, dean of studies, Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute, Kolkata. “But he was a film scholar and essayist, and that was more than what Ray was. He was the man who first used 18mm lenses, and wide-angle and low-angle shots in cinema.”

The ‘New Wave’ offered such experimental fare, but mainstream Bengali cinema could not digest it. It was too abstract. The new modes of narration were too foreign and were considered too intellectual for a major chunk of the populace. Mainstream cinema wanted simpler (not necessarily simplistic) narration and solid background music. Ray was a master at this. He had, for instance, made Kishore Kumar sing Rabindra Sangeet in Charulata.

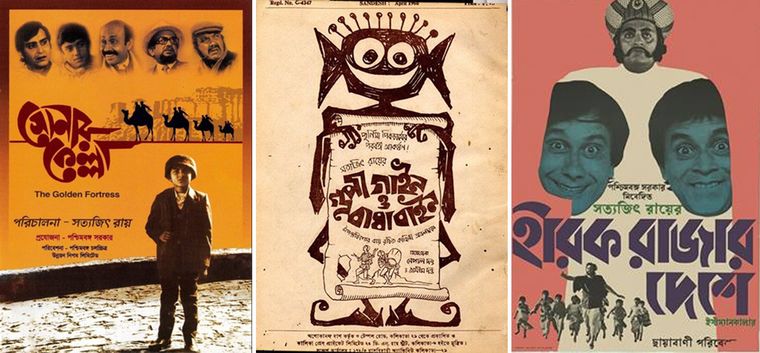

Though Ray made his share of contemporary, political films, he could not completely ditch books. He saw the turmoil Bengal was in, and focused on bringing joy to the cinema goer with some eclectic choices. He took inspiration from his grandfather—children’s writer Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury—and also began writing his own short stories. Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, a fantasy adventure comedy, was based on Chowdhury’s story. He also dabbled in science-fiction and detective stories, including the hugely popular Feluda series, which he wrote. “[These were] the rarest of the rare in Indian cinema,” said Gopalakrishnan.

Inspired by Ray’s unorthodox movies, several other filmmakers, including Tapan Sinha, made similar movies based on well-known works of fiction.

For Viswanathan, each of Ray’s 29 feature films and seven documentaries was reflective of what he stood for—Ray would let the story unfold, and different people would see their own versions in it. That is why, he said, Ray’s films are timeless.

Come the 1980s, the political upheaval in Bengal subsided and left-wing trade-unionism started gaining ground. Ghatak had died; Ray became sick and stopped outdoor shooting. Barring a few names, like Goutam Ghose, the left-inspired generation had a lack of talented filmmakers. The ruling left became a self-appointed custodian of what “good cinema” meant; it was widely considered the beginning of the downfall for mainstream Bengali cinema.

With liberalisation, there was a proliferation of English-medium schools; the aspirations of being western took many in the state away from their mother tongue. There were fewer and fewer writers who used Bangla.

The industry started looking to mainstream Hindi, Telugu and Tamil cinema for survival. The corporate houses that came in started prioritising money—something Ray, Sen and Ghatak had not done—and it was easier to ape what worked in mainstream cinema elsewhere. The films lacked depth, were “unrealistic” and were full of “mindless violence”.

A divide was forming within society. While the elite urban watched parallel cinema from the likes of Rituparno Ghosh; the Bangla-speaking rural folk were served sub-par fare. They, too, started rejecting Bengali cinema.

“When I hear that today’s popular Bengali movies are inspired by Telugu and Tamil films, I feel shocked,” said Gopalakrishnan. “How could Bengali films stoop to such lows is beyond my comprehension. We need a close look at what is happening in Bengal, culturally.”

Today in Kolkata, only around 10 single-screen theatres are in business; they survive thanks to Hindi cinema. At least three districts of Bengal—Midnapore, Bankura and Purulia—do not have a proper cinema hall.

The Bengali film industry, which was worth an estimated Rs500 crore (not adjusted for inflation) in the 1980s, today does much less business. “The industry is valued at Rs150 crore to Rs175 crore in terms of expected revenue with negligible growth,” said Subhojit Roy, secretary of the Eastern Chamber of Commerce. “According to industry estimates… [only] five to six films in Bengal can generate surplus revenue. Almost 70 per cent of the box office collection of Bengali films today is claimed by 22 to 25 films from the three or four large production houses.”

Purnima Pictures, which produced three Ray films, runs a chain of cinema halls in the state. It now relies on Hindi films. Said managing director Arijit Dutta: “When Rituparno Ghosh began making films, only the Kolkata audience saw them. The films did not make hefty profits, but they did well. The current movies are not saleable, except for one or two.”

Though Dutta’s ancestors, Asim Dutta and Nepal Dutta, had produced path-breaking films, he has no interest in doing so himself. “The corporates are ruling along with the unions. For instance, I will have to hire a light man even if I do not need one. The corporates have the money. If I start producing a film, I would not be able to complete it,” said Dutta. “We had seen militant trade unionism in every sphere during the left rule. Today, we see that at a very high level in film production.”

At the Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute, an autonomous body funded by the Union culture ministry, the scene is telling. Students from China, Japan and Korea study there, and make good cinema once they go back home. “Our boys, after passing out, work for OTT platforms or some of them shoot wedding videos for the rich,” said Sounak Kar, a faculty member.

Said Jayabrata Das, a former SRFTI student: “We have been taught to make artistic and highly acclaimed films. But the industry will not accept that. Who then will pay for it? So, I have decided to mix both for the sake of my career.”

He is currently making a potboiler with a few lakh rupees he managed to gather. “At least these would sell on OTT platforms,” he said. “Otherwise, I have no chance as a filmmaker. Some actors in Bengali films have agreed to work in my film at a very low rate.” Most of the actors he got onboard are the ones trying to revive their careers after a failed political gamble.

For Das, Rituparno Ghosh was the only modern director to have made “good” movies in the past two decades. “But even though he started well with Unishe April, he later began addressing the producer’s need rather than focusing on the true art form he believed in,” he said. “Also, he had some personal problems that affected his professional life.”

The current status of Bengali cinema is perhaps best summed up in this anecdote. Gopalakrishnan was on the committee to celebrate Tagore’s 150th birth anniversary in 2011. The committee, which then prime minister Manmohan Singh had convened, was about to make a documentary on Tagore. Gopalakrishnan resisted. “No other film could be better than Ray’s documentary on Tagore,” he said. “Copies of that documentary should be sent to every school in the country.”