On the morning of May 22, 1991, I got a call from Delhi. It was K.P.S. Gill, my boss and director general of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF). I was inspector general, CRPF, posted at Hyderabad. Gill told me that the government wanted me to investigate Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination. I was both shocked and sad by his death. Like many others in the country, I had liked Rajiv, and had happened to know him, too.

Then came the call from S.K. Datta, director of the Central Bureau of Investigation. He said neither the Intelligence Bureau nor the Research and Analysis Wing could throw any light on the assassins. It was unlike the Mahatma Gandhi or the Indira Gandhi assassinations, where the killers were caught red-handed. It may remain a mystery, like the John F. Kennedy assassination, he said.

I agreed to take up the case on three conditions: I would brook no political interference in the investigation, I would not resort to third-degree and would strictly go by the law, and I should be allowed to continue in the CRPF. Datta asked me when I could leave for Tamil Nadu. ‘Straight away,’ I replied. An Air India flight was cancelled and redirected to Chennai. On the flight with me was one company of CRPF men; the Tamil Nadu director general of police had wanted the security on the ground to be strengthened because of the tense situation. Senior officers of the Tamil Nadu Police and CBI met me at Chennai airport. The refrain was: “Why did you take up the case? It is a blind case.” I said, “Do not demotivate me. Nothing is impossible. We will crack this case.”

We worked 20 hours a day, every day, the whole year, without a break. I had promised that I would go from the crime to the criminal, and we did just that.

It was indeed a blind case with no ready leads. The intelligence agencies could not say with certainty who was involved in the killing. After we said that the assassins were from the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), my friends in the CBI called me and said that the case had been offered to them, but they had all said no. They felt that it would be impossible to solve, and their own lives would be at risk if they manage to identify the group that sent the assassins. They advised me to withdraw from the case now that we had zeroed in on the LTTE, especially because I was from Tamil Nadu. But I stuck to the job given to me.

It was a mammoth exercise. Thousands of individuals were examined, over a thousand witnesses were cited in the charge-sheet and over 10,000 pages of witness statements were submitted to the court. There was an enormous amount of documentation, 500 video cassettes and over a lakh photographs.

Also read

- A Kindred Spirit recalls Rajiv Gandhi memories

- Rajiv Gandhi: The caring and cordial democrat

- Rajiv Gandhi opened the doors for 1991 reforms: Montek Singh Ahluwalia

- How Rajiv Gandhi reset India’s relationship with the west: Ravni Thakur

- Politicians of my generation were inspired by Rajiv Gandhi: Bhupesh Baghel

- Rajiv knew a divided Sri Lanka would create problems for India: Mani Shankar Aiyar

- Political naivety overshadowed much of Rajiv Gandhi’s positive work: Rasheed Kidwai

- How Rajiv Gandhi’s peace deals materialised: Vappala Balachandran

Among our challenges was finding a building to hold those in our custody. The Tamil Nadu police were reluctant to hold them in their lock-ups because of the tense atmosphere. We identified an army unit in Chennai. However, the officers declined, despite directions from the highest levels in New Delhi. They would not have anything to do with the LTTE. They had had enough in Sri Lanka. Finally, we made a makeshift lock-up on the SIT premises.

Attempts were made by politicians to interfere in the case, but no one dared to make a direct interference. Allegations were made against several political personalities. But we went only by the facts before us.

The charge-sheet was filed on May 20, 1992. Later, two commissions of inquiry were constituted—the Justice J.S. Verma Commission and the Justice M.C. Jain Commission. This I feel was a politically motivated decision, as there were political forces that wanted to prolong the investigation. For such forces, the multi-disciplinary monitoring agency came in handy. After three decades, and after spending crores of rupees and sending people around the world, they found nothing beyond what I found.

The investigation took a toll on my mental peace, and had an impact on my family. My wife, who was under constant stress, suffered a heart attack. My children were quite young then.

Once, Dr P.C. Alexander, who was governor of Maharashtra, told me, “Mr Karthikeyan, you must be the most harassed man in the whole country.” I said that till it is not my time to leave, nobody can take my life, and when my moment comes, nobody can save me.

I would get a call from Vincent George, Sonia Gandhi's personal secretary, every night—sometimes even in the middle of the night—asking me about developments in the case. One day, I said, “What can I say every day?” He said, “The family is awake. They will not go to sleep (unless they hear from you).”

Once, when I was in Delhi for a hearing of the Justice Verma Commission, George asked me to meet with Sonia. I took permission from the home minister and met her. Throughout the 90-minute meeting, she cried. Priyanka Gandhi asked me some questions. As I got up to leave, Sonia came up to me and said, “Thank you very much.”

A lot has been written and said about the investigation in the last 30 years. However, I draw satisfaction from the fact that our findings were upheld by the judiciary, which even praised us for the meticulousness with which we probed the case.

I was invited to make a presentation on the investigation at the INTERPOL headquarters in Lyon, France. The assembly of experts at the INTERPOL said it was a model investigation, since political assassinations are never solved and never reach the court.

This was the first case where the assassination of a world leader by a human bomb was convincingly solved, prosecuted, convicted by the highest court in the country and also defended before two commissions of inquiry.

—As told to Soni Mishra

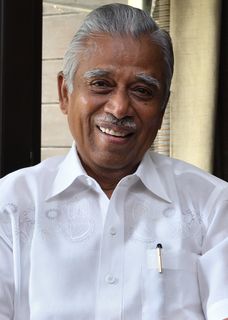

R. Karthikeyan headed the CBI Special Investigation Team that probed the Rajiv Gandhi assassination. The retired IPS officer has been director, CBI, and director general, National Human Rights Commission.