Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru was in jail when Indira, his daughter, gave birth to a baby boy in Bombay on August 20, 1944. It was only seven months later that he got a fleeting glimpse of Indira and Feroze Gandhi’s first-born. As Nehru was being shifted to Naini Jail in Allahabad, Indira and Feroze held the baby aloft under a dim streetlight so that the grandfather could see his grandson when the prison van passed by.

Nehru christened the child Rajiv Ratna, or jewel-adorned lotus. He had chosen the name carefully—it was a combination of his own name and that of his late wife, Kamala. The word Kamala, too, means lotus. And Ratna is another word for Jawahar, which means jewel.

The family’s rich legacy—of its contribution to India’s freedom struggle and its pre-eminence in the country’s body politic—was thus symbolically transferred to the newborn. Greatness was thrust upon Rajiv Gandhi at birth, and he had to measure up to it.

For Rajiv, though, any association with his family’s greatness was a source of unease. An anecdote from his school days shows this. Prime minister Nehru was visiting the Doon School in Dehradun, where Rajiv and his younger brother, Sanjay, were studying. As Nehru lunched in the dining hall of his grandson’s hostel, Rajiv was nowhere to be found. He had gone into hiding, embarrassed at the prospect of being associated with his illustrious grandfather.

Rajiv was Indira’s apolitical son, even as Sanjay emerged as the rising star of the Congress and her heir apparent. Ill at ease in the limelight, Rajiv detested politics. He was happy being a private citizen living away from the public eye, employed as a pilot in the Indian Airlines and leading a comfortable life with wife, Sonia, and children, Rahul and Priyanka.

But in 1981, months after Sanjay died in a plane crash, Rajiv had to give up his pilot’s uniform and don the Gandhi cap. “Somebody has to help mummy,” he said, as he made a reluctant entry into politics.

Yet another tragic turn of events placed him right at the centre of it all. Indira was shot dead by her own bodyguards on October 31, 1984, and Rajiv was sworn in as prime minister.

Only 40 years old, he became the country’s youngest prime minister. His freshness and genteel demeanour set him apart from traditional politicians. His good looks and youthfulness wowed the country. Rajiv was exactly what an aspirational India was waiting for as he spelt out his vision to take the country into the 21st century. He was also the Mr Clean who would rid the system of its corrupt ways.

Destiny had set in motion its own plans. The young leader, who in his boyhood was in awe of his heritage, was feted as a modernist leader like his grandfather. Rajiv won a huge mandate, which remains unbeaten, in the Lok Sabha elections held in December 1984. While it was the result of a nation shocked by Indira’s assassination, it boosted his capacity to take bold decisions.

Rajiv was a man of change. His first legislative initiative was the anti-defection law, meant to end the ‘Aaya Ram, Gaya Ram’ culture. His government’s first budget was hailed as perfect. It provided the basis for economic reforms through a more liberal taxation regime and de-regulation. Rajiv believed that the private sector had to be encouraged rather than mistrusted, and saw in the aspirational middle class the potential to drive economic growth.

Also read

- A Kindred Spirit recalls Rajiv Gandhi memories

- Rajiv Gandhi opened the doors for 1991 reforms: Montek Singh Ahluwalia

- How Rajiv Gandhi reset India’s relationship with the west: Ravni Thakur

- Politicians of my generation were inspired by Rajiv Gandhi: Bhupesh Baghel

- Rajiv knew a divided Sri Lanka would create problems for India: Mani Shankar Aiyar

- Political naivety overshadowed much of Rajiv Gandhi’s positive work: Rasheed Kidwai

- How Rajiv Gandhi’s peace deals materialised: Vappala Balachandran

The computer became the symbol of Rajiv’s modernisation thrust. In the face of derision from older politicians, he pushed for popularising computers. The foundations of the country’s software industry were laid. The telecom network was expanded and PCOs, or public call offices, brought connectivity to the hinterland. Six technology missions were set up in the fields of telecom, rural drinking water, literacy, immunisation, milk production and oilseeds.

The flurry of new initiatives included the National Policy on Education, aimed at revamping higher education. Rajiv announced his intent to take the decision-making process to the grassroots through the panchayati raj system. In keeping with his connect with the youth, he reduced the minimum age to vote to 18.

Rajiv sought to be a man of peace, signing accords in Punjab, Assam, Jammu and Kashmir, and Mizoram. While not all the agreements achieved desired results, they were bold moves aimed at finding a solution to long-standing issues and bringing peace and stability.

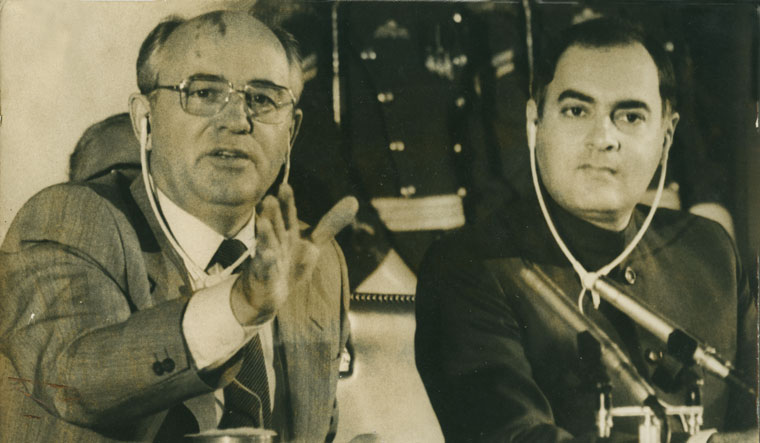

On his visits abroad, Rajiv reflected charisma and statesmanship. He established personal rapport with Mikhail Gorbachev of the USSR, and was regarded with admiration by the Ronald Reagan administration in the US. His visit to China in 1988, the first top-level engagement between the two countries in 26 years, stood apart for the warm welcome that the formidable Deng Xiaoping gave to his “young friend”.

In 1988, Rajiv also became the first Indian prime minister to visit Pakistan in 28 years. His camaraderie with Pakistan premier Benazir Bhutto held out the promise of improving relations between the two countries.

India’s proactiveness in the neighbourhood during his time remains unmatched. He sought a politically negotiated settlement to the Tamil issue in Sri Lanka. He responded to SOS messages from the Maldives and the Seychelles, and helped thwart coup attempts in the two nations by sending across Indian forces.

Rajiv came with the promise of changing the way politics was done. This was spelt out in his eloquent speech at the centenary session of the AICC in Bombay in December 1985. He said he wanted to rid the Congress of “power-brokers”, who had changed the party from a mass movement into a feudal oligarchy.

Soon enough, though, the promise of change was replaced with cynical realpolitik. Rajiv’s decision to bring in a law to overturn the Supreme Court’s Shah Bano judgment dented his secular image. His critics claimed the law was only a red herring, for his government soon opened the locked gates of the Babri Masjid-Ram janmabhoomi site, in an alleged bid to secure Hindu votes.

Rajiv’s Mr Clean image was sullied by allegations of corruption, particularly the Bofors scandal, the Fairfax issue and the HDW submarine deal. It was felt that the man who had batted for transparency in the functioning of the government gave opaque responses to accusations of corruption.

Even his bold initiative in Sri Lanka to end the Tamil strife did not end as expected. The decision to send the Indian Peace Keeping Force to disarm Tamil rebels backfired, with the Indian forces incurring huge losses in their battles with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.

As the magic wore off, Rajiv’s inner circle, described by the Congress’s old guard as the new power-brokers, disintegrated. Friends turned into foes, and ultimately, he was surrounded by the same power-brokers whom he had wanted to oust from the party. The desire for change was replaced by myopic political moves, aimed at surviving the coup attempts by disgruntled party veterans.

The massive mandate was rendered meaningless. Rajiv was no longer the harbinger of a new kind of politics. He had failed to change the system, was engulfed by it, and was no different now as he, too, was seen as corrupt.

After a brief interlude provided by the V.P. Singh and Chandra Shekhar governments, Rajiv appeared surer as a politician and a leader. But he was saddled with the same old party and weighed down by the same old problems he had failed to resolve. Also, the politics of the country had changed drastically post the implementation of the Mandal commission report and the BJP’s rathyatra for Ram Temple. Mandal and kamandal would prove to be the undoing of the Congress.

Rajiv, however, plunged enthusiastically into campaigning for the Lok Sabha elections of 1991. He believed he would get a second chance. But his quest for an opportunity to redeem himself remained unfulfilled. As if in a Greek tragedy, the ghosts from the past returned to claim him. On the night of May 21, 1991, as he arrived to address a public meeting in Sriperumbudur, a small town in Tamil Nadu, Rajiv met his end in a massive explosion triggered by the LTTE.

Thirty years after his death, Rajiv has remained alive in the national conscience through the enduring impact of his brief tenure. He will forever remain young, even as the nation ages, and will be remembered for inspiring a generation of Indians to dream big.