Thirty years after he passed away, it is relevant to look back and reflect on Rajiv Gandhi’s contribution to India’s economic reforms. I had a ringside view of policy in those years, having joined the Prime Minister’s Office in January 1985. This article offers an abbreviated, personal assessment. Readers who want a fuller account can get it from my book, Backstage: The Story Behind India’s High Growth Years (Rupa Publications, 2020).

Rajiv raised high hopes when, in his very first public speech, he spoke of preparing India for the 21st century. As a recent entrant into politics, he was completely free of the ideological baggage carried by older politicians. This encouraged the expectation that change was on the agenda. This was strengthened when, speaking in Parliament in February 1985, he said, “We cannot pretend to be equal to other countries when we are operating systems that are 20 years old or 10 years out of date.” No prime minister had ever asserted quite so emphatically that our systems needed to change.

As it happened, the system change did not really begin until 1991. However, Rajiv took a number of initiatives which could be called the first steps in economic reforms. He was the first top politician to recognise that a new, aspirational middle class was emerging, with more money to spend and demands for modern consumer goods which could not be ignored. This necessitated a departure from the P.C. Mahalanobis strategy, which was at the core of much of Indian planning, and was based on prioritising the production of capital goods (largely produced in the public sector) while actively discouraging the production of durable consumer goods.

Since the private sector was best positioned to meet the new demands, it had to be given freedom to expand and respond to these new demands. Rajiv was the first prime minister to signal a new approach to the private sector. He met representatives of the private sector much more frequently than any of his predecessors had done. He also broke visibly with tradition by taking business delegations with him on his international trips.

These symbolic steps were accompanied by efforts to create an environment conducive to private investment. Tax rates were lowered with a promise of stability. Domestic indirect taxes were modified to allow credit for taxes paid on inputs, a first step which culminated 30 years later in the Goods and Services Tax. The industrial licencing system was not abolished—that systemic change happened only in 1991—but it was made much more flexible. It was announced that the capital market would have an independent regulator; the Securities and Exchange Board of India was set up in 1987, paving the way for developing a modern, well-regulated stock market.

Rajiv saw telecom connectivity not as a demand of upper-income groups in urban areas, but as something that was equally important for those in rural areas. Sam Pitroda was inducted into the government to lead a mission to expand telecom access. The real telecom revolution happened only a decade later, when mobile telephony became possible and the sector was opened for private-sector service providers. But it was in the Rajiv years that telecom became a priority area. Privately managed STD booths were a major innovation that made a huge difference to the lives of many people.

Also read

- A Kindred Spirit recalls Rajiv Gandhi memories

- Rajiv Gandhi: The caring and cordial democrat

- How Rajiv Gandhi reset India’s relationship with the west: Ravni Thakur

- Politicians of my generation were inspired by Rajiv Gandhi: Bhupesh Baghel

- Rajiv knew a divided Sri Lanka would create problems for India: Mani Shankar Aiyar

- Political naivety overshadowed much of Rajiv Gandhi’s positive work: Rasheed Kidwai

- How Rajiv Gandhi’s peace deals materialised: Vappala Balachandran

He was an early advocate of computerisation, pushing for its induction in different parts of the government. He also contributed to India’s subsequent emergence as a software player. When Texas Instruments decided to set up its first research and development facility abroad in Bangalore, the policy in place at the time did not allow them to operate a dedicated satellite facility to allow seamless connectivity with Houston. Rajiv took a personal interest in ensuring that this problem was satisfactorily resolved. The subsequent success of the TI venture set the trend for other multinationals to set up similar ventures in India.

I should add that he did not agree with all the reformist ideas of the time. He did not, for example, favour privatisation of the public sector. However, he always encouraged us to put new ideas forward and there were many occasions when I tried to persuade him that our policies were excessively protective of the public sector, reserving too many areas exclusively for it, and also retaining public-sector presence in areas such as bakeries, hotels and manufacture of scooters, where the private sector would do a better job.

Perhaps because he had worked in Indian Airlines, he had a deep affection for the public sector and felt that with the right management culture it could become efficient as the private sector. But he did accept that there were too many public-sector units that were perennially loss-making and these should either be privatised or closed. Scooters India was an obvious candidate, and he agreed that we should see if it could be privatised. Bajaj Auto offered a reasonable deal to take over the unit on certain conditions, but resistance from the ministry scuttled the effort. In January 2021, fully 35 years later, the government decided to close it!

Rajiv’s energies were not just focused on industry. He spent a great deal of time visiting villages, to see how our rural development programmes worked on the ground. He saw that these programmes suffered from large leakages due to administrative inefficiency and corruption, and came to the conclusion that the only solution was to delegate greater authority to locally elected bodies. This led to the idea of giving constitutional status to panchayati raj institutions (PRIs) in rural areas, and urban local bodies in urban areas.

Instead of resorting to top-down decision-making—he certainly had the parliamentary majority to do so—he embarked on an extensive consultation process beginning with four regional conferences of district magistrates, which he addressed himself. This finally led to a political decision in a conference of chief ministers, to amend the Constitution to devolve authority to the third tier of government. The amendments could not be passed before the end of his term and were finally passed under the Narasimha Rao government. As it happened, the extent of devolution remains incomplete, mainly because the states have proved unwilling to devolve finances to the lower levels.

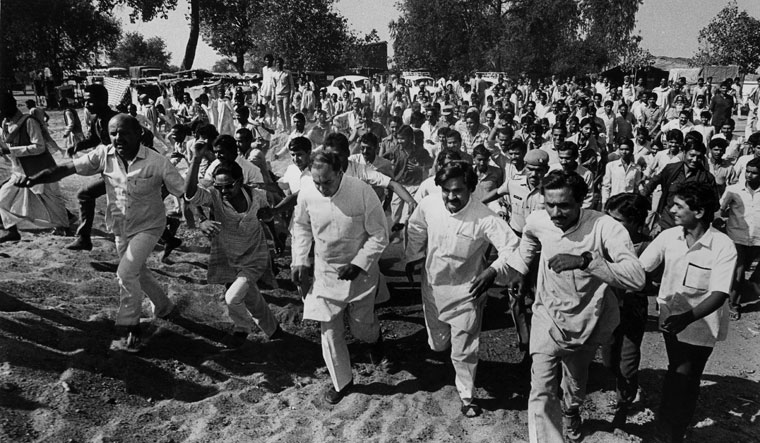

It is legitimate to ask whether, given the huge majority of 408 seats in the Lok Sabha, he could have done more to bring about systemic changes. One has to keep in mind that the majority he had, which was larger than the majority enjoyed by the government today, was not a mandate for change. It was the result of a nation shocked by the assassination of a prime minister, and was therefore more of a mandate for stability and continuity. Nor did the election come after a period of poor economic performance, which could be a reason for making radical changes in economic policy, as was the case in 1991.

It could still be argued that Rajiv should have pushed more vigorously for the systemic reforms he wanted. I think he suffered from two constraints. One was that the Congress, which he led, was itself not convinced about the need for reforms. To carry the party with him, he needed a like-minded political team, committed to a common vision of change, working assiduously to build a consensus, first within the party and then beyond.

He did have a young, like-minded team, but it fell apart very quickly for different reasons. The first to go was V.P. Singh, a key member of his economic team. Arun Singh, a close friend and confidant, left because of differences on how the Bofors issue should have been handled. Arif Mohammed Khan left because of the Shah Bano misstep. Arun Nehru left for his own ambitions.

These departures did not affect Rajiv’s unquestioned leadership of the party, but they left him surrounded by a coterie of the old guard, the very “brokers of power” he had attacked in his speech at the Congress centenary celebrations in December 1985. They never questioned his leadership, but they did not really share his vision of modernising our systems.

In a magazine interview shortly after stepping down as prime minister, Rajiv Gandhi was asked why he was not able to achieve more. He responded frankly that inexperience was a probable reason. He had a point. Deng Xiaoping, who masterminded China’s reforms, had decades of political experience before he reached the top in 1978, after Mao’s death. Over the next 15 years, he worked hard to build a team that subscribed to his vision and he succeeded in dismantling Mao’s legacy without ever criticising him directly. Rajiv had entered politics only a few years before he became prime minister and after the first two years, the Bofors controversy and other missteps weakened him considerably. Had he lived to have a second term, he would have had much more experience and perhaps brought about more substantive changes.

The second reason why he was not able to do more was that the system did not throw up well-conceived agendas for change. Rajiv often said he wanted out-of-the-box thinking and got very little of it. The Planning Commission could have been a source of such ideas, but over the years it had become a mechanism for allocating scarce public resources among competing ministries. Manmohan Singh, who was deputy chairman and later masterminded the economic reforms, left in 1987 to join the South Commission, and was replaced by P. Shiv Shankar, a traditional Congress politician with little interest in planning and even less in economic reforms. The ministries themselves only dusted up old ideas and asked for more money while promising only marginally better performance.

I must confess that I myself came to appreciate the problem only late in my stay in the PMO. As the elections were underway, B.G. Deshmukh, then principal secretary to the prime minister, asked me why we found it so difficult to make changes in policy. I thought hard about it and told him that the fault lay in the way policies were decided in our system. Each ministry was assigned specified objectives and controlled certain policies, but most objectives needed changes not just in policies under the control of the concerned ministry, but also policies controlled by other ministries. However, each ministry acted as a silo, trying to achieve its objectives relying largely on the policies under its control. As a result, there was not enough thinking on the changes needed in the system as a whole.

Export promotion exemplified the problem. It was the job of the ministry of commerce, but the only policy that ministry controlled was export subsidy. The expert view was that our high levels of protection raised our cost structure and discriminated against exports in favour of import substitution. Improved export performance required lowering of import tariffs to reduce the high cost structure and offsetting the competitive weakness resulting from lower tariffs by a depreciation of the currency. This would not only help domestic producers to compete more effectively against imports, but also provide direct support for exporters. However, tariffs and exchange rates were controlled by the finance ministry, and the ministry of industry was a strong supporter of high tariffs to protect domestic industry. There was no way the ministry of commerce could bring about a change in all these policies, so it contented itself with asking for more funds for export subsidies!

Deshmukh agreed with my assessment and asked me to prepare a paper outlining a core set of inter-related reforms, which we could give to Rajiv if he returned to office. I started working on it and the paper was ultimately presented to V.P. Singh when he became prime minister. It came to be known as the ‘M Document’ and generated a huge controversy. Nothing was done then, but many of the ideas contained therein became part of the reform agenda of 1991.

Rajiv Gandhi’s emphasis on out-of-the-box solutions and his belief in technology remain relevant today as we focus on contemporary problems such as the immediate management of the pandemic, or orchestrating a recovery after the pandemic, or longer-term challenges such as creating a viable health system and dealing with climate change. We need to move away from “more of the same” responses and explore new options, leveraging modern technology to our advantage. To do this effectively, we need to consult extensively with relevant experts, most of whom are outside the government, and also with the private sector, which is now a major player. And in a democracy, we also need to explain to the wider public why new approaches are necessary. l

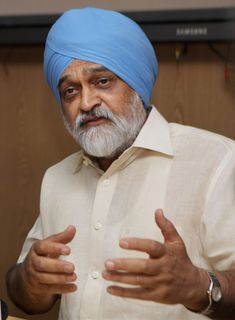

Ahluwalia is a prominent economist who played an important role in liberalising the Indian economy. He served as special secretary to prime ministers Rajiv Gandhi and V.P. Singh, and was deputy chairman of the Planning Commission from 2004 to 2014.