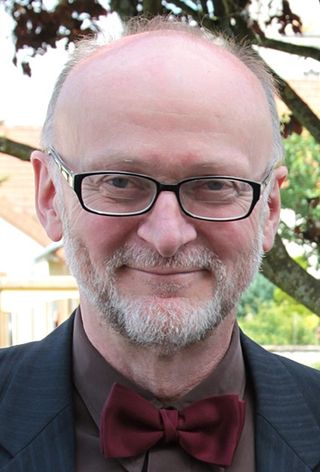

Robert Fowke has spent years busting myths—be it historical myths for children or in poetry. He wrote about the sailor that inspired Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’. Lately, Fowke has found a story closer to home that he hopes to put into perspective.

A descendant of Robert Clive through his wife, Margaret, Fowke is writing a book on Lady Clive. A couple of years ago, he had come to Chennai, where the Clives had gotten married. He disputes that Clive was a monster. “I know [William] Dalrymple says Clive was a monster and a racist,” says Fowke, over the phone from Shropshire. “But he wasn’t.” Excerpts from an interview:

Q | What do you make of this petition to remove Clive’s statue?Å

A| I think it is necessary that we look at the shared historical narrative that we have in the country so that it includes people who came from the New Commonwealth in the last 50 years. I have no problem with that at all. I think there is a danger now that it becomes indiscriminateì you end up in a situation where you could say that anyone who contributed to British history, contributed to the British empire.ì That everything about the British empire is bad without exception, which is kind of simplistic. We need to look with detail and empathy at people from the past and not just dismiss them because they are associated with our own British history.

I found that Indian people are far more open-mindedì [about] the history of the association between Britain and India than British people are themselves.

Q | As a descendant of Clive, do you think that the Black Lives Matter movement is forcing you to relook at his legacy? Do you think that you are being forced to feel apologetic for the past?

A | It has become very divisive. Obviously, he was a man with many faults. In particular, he was very greedy. He was also a very brave man, a tormented soul. He achieved a great deal, in British terms. He was also before the empire—there was no British empire at that time. You should not really judge him for the very racist attitude that developed in the 19thÅcentury. It is unfair on him as a historical character that I am personally, emotionally very involved with. It is not right to show such disrespect to somebody of that calibre.

Q | As someone who has written extensively on history, do you think the Black Lives Matter movement is reducing history to this rather simplistic binary of black vs white, victim vs victor?

A | History is almost a bunch of fiction, isn’t it? Because you have to use a process of selection in order to write our book. It is so much a constructed thing. It can almost be seen as fiction. For instance, Dalrymple, for narrative purpose, sets Clive against Warren Hastings. Anyone who knows about that period knows that Clive proposed Hastings to go out to India. They were not rivals. In a way, Hastings [was] continuing the politics that Clive had already suggested.

Q |Clive was judged for his actions by his peers.

A | This is interesting. He was judged at that time very harshly by [Edmund] Burke and [Horace] Walpole. Very falsely in many ways. Obviously, he took a huge amount of money after Plassey. But by the standards of the time in India it was not much... it incited envy at home more than anything else. He acquitted himself very well in parliament. [William] Pitt said he was one of the greatest orators of his time. He was a remarkable man.

Q |He battled mental illness, which is not much talked about.

A | He was a bit like Churchill, I think, a manic depressive. He was so driven. The number of times he risked his life is extraordinary. He was not a military mind, but he was good at fighting. To be driven and to be so ambitious—I can hardly imagine it myself.

Q |You think people are judging him by 21stÅcentury mores?

A | Which is absurd. Even judging by the standards of his time, he was humane. If you take a look at other historical figures who have had great victory—Wellington or Napoleon—tens of thousands of people died. In the Battle of Plassey, there were only a few hundred. People were dying in tens of thousands in massacres that were happening at the end of the Mughal empire. Clive didn’t do that. He wasn’t a bloodthirsty man at all. He wasn’t even really a soldier.

Q |But the idea was that he amassed so much wealth.

A | That is what people don’t like about him. But then to put on his shoulders the process of the empire thereafter is not good history.

Q |You are writing a book on Lady Clive.

A | Margaret was a lovely woman. She was clever and funny. Her family are called Maskelyne. Their mother was a clever woman interested in astronomy. Margaret herself was interested in astronomy. They were all passionate about music. She had interests that were more intellectual than Clive. But it was a happy marriage. They were evenly matched. I can imagine he cannot be always likeable. But she was always entertaining. She complemented him. I am charmed by her. I sort of fell in love, reading about her.

Q |Were you always aware of the Clive association?

A | My family was involved with the East India Company from 1700. I sort of knew about it very vaguely. You know how you hear those myths and stories. I thought I would like to find out more in detail. We have this huge archive in The British Library. It is the largest archive of private letters and they are all associated with my family. What stood out for me were the women’s letters. The men’s letters are more about business or politics. The women’s letters are more emotional, therefore intriguing.

Q |What were you looking for in Chennai?

A | I was trying to retrace where they [the Clives] were. It was immensely rewarding.

Q |Do the letters throw light on the Clives’

marriage?

A | You can’t achieve what Clive achieved. I know those who disagree won’t call them achievements, but they were, without being very clever. They say he would sit quietly in a room. But then, if there was a subject that he was interested in, his observations would be very acute. He could be funny. He was quite a humorous man. I love the anecdote of an aunt—she would sit on his knee and he would coax her into telling all the naughty words she had learnt at school.

Q |What do you think of relooking at history with the Black Lives Matter movement?

A | I am sure it is completely helpful. It is very different for us. You haven’t had this immigration into India that we have had into Britain. But if you, say, had a population which was European and discontented, you would need to integrate their historical narrative with yours. We have the same problem. The problem is if you are from an Indian background or an African background, then Clive is not an ancestor. There is a lack of belonging. We need to create that belonging. But I am not sure, I hate to use it, it sounds a bit rude, but this cultural victimhood really benefits the people who are expressing it so stronglyì. I recognise the need to do it. But I don’t think showing disrespect to someone like Clive really helps.