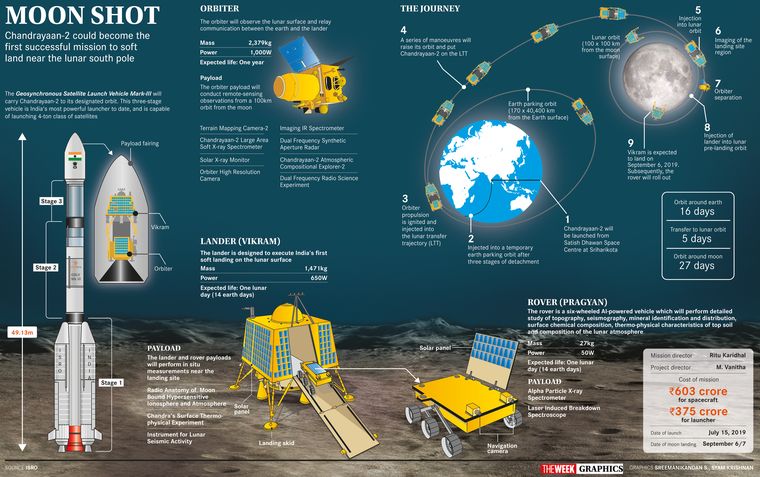

Vikram is ready for a date with the moon. At Sriharikota, the lunar lander waits to fire off on July 15 on board the GSLV Mk-III, aka Bahubali, to its new home. The destination is an unexplored high plain between two craters, Manzinus C and Simpelius N, close to the southern tip of the moon. It is a sweet coincidence that this lander, named after the father of India’s space programme, Vikram Sarabhai, is making its journey on Sarabhai’s birth centenary year, and also in the golden jubilee year of Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO).

The predawn flight is expected to take off at 2:51am. Yet, the newly commissioned launch view gallery at the spaceport will be filled to capacity by those eager to see history unfurl. Chandrayaan-2, India’s second lunar probe, aims to make a soft landing on the moon on September 7. This is a challenging endeavour for any country; more than half the world’s 38 previous attempts have failed. Only earlier this year, Israel’s maiden lunar probe, Beresheet, lost all communication with its earth station, barely 10km from its destination. It crash-landed on the moon, ending its explorations. Only three countries have managed soft landings on the moon—USA, Soviet Union and China. No one has aimed for a destination so close to the South Pole, though China’s Chang-e 4 trailblazed with a southern hemisphere landing on the dark side of the moon earlier this year. India’s mission, therefore, is a bold one.

Moon journeys are tricky business. The distance of about 3,844 lakh km requires great trajectory accuracy, as even a minor veering off course could result in the craft wandering in space, far from its intended destination. Space environments are hostile, and the risk of losing communication with the ground station (India’s is the Indian Deep Space Network antenna at Byalalu, Karnataka) is high. The moon is not a static body; it rotates on its axis and revolves around the earth, which itself is revolving around the sun. The lunar capture (getting into the moon’s orbit) requires some mind-boggling calculations. The moon has a lumpy gravity, because of its uneven mass and extreme temperature variation. In the destination desired for, this ranges from -157°C to 121°C, which is harsh on the hardware.

Finally, the landing itself has to be finely calibrated, kicking up as little dust as possible. Even a grain of dust is enough to disrupt the lander’s functions and render it useless. ISRO is not taking its chances. It chose this particular landing site because, from what we know of the moon, the terrain at this spot is not too pockmarked or rocky. ISRO also plans to do more imaging of the site to minimise a rocky landing. Since the probe will enter the lunar orbit 27 days before the landing, there will be time enough to do better mapping with the probe.

While India has proven technology with Chandrayaan-1 and the Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) for most of the steps, the soft landing is a new game altogether. Chandrayaan-1 had an orbiter and a lander, which was an impact probe. The lander’s job was to take rapid images of the moon as it detached from the orbiter and fell on the surface. Once it crashed onto the moon, it became inert. Chandrayaan-2, however, will have an orbiter, as well as a lander (Vikram) and rover (Pragyan). The latter two have to land intact on the moon, because they have a full lunar day’s work (14 earth days) ahead of them. To achieve this, they will first be lowered from a 100km orbit around the moon to a 30km one. Then, they will descend, very slowly, to minimise impact damage. ISRO chairperson K. Sivan calls the 15 minutes it will take Vikram to land on the moon as the most “terrifying” moments of the mission. ISRO has already had one experience of a bad test landing at the simulator in Chitradurga in April, which damaged the legs of the lander.

Vikram has three payloads—Rambha, Chaste and ILSA (see graphics)—with which it will study moonquakes, moon terrain and its ionosphere. Before this, however, it will let Pragyan out. This six-wheeled rover is capable of travelling half a kilometre away from the lander, very slowly (1cm/sec). It is equipped with a spectroscope and a spectrometer, with which it can analyse the mineral composition of the terrain, and perhaps sniff out more water deposits. Since the moon does not have an atmosphere, water is not present in liquid form.

While Vikram can make direct contact with India’s Deep Space Network to transmit its findings, Pragyan will report to Vikram. As both of them are largely solar-powered, they are expected to have a working life only as long as they get the sun—14 earth days. The orbiter, though, has a mission life of one year. It could, however, go on and on, like MOM, which has far outlived its mission life of six months and continues to send data to earth even four years later.

Chandrayaan-2 has taken 11 years to be realised, having faced several setbacks. It started with the termination of a joint exploration with Russia after the country’s Fobos-Grunt mission failure in 2011. Russia was supposed to provide the lander, and so following the termination of the deal, ISRO was forced to develop it from scratch. This took time. ISRO had planned for an April launch last year, but a review revealed the landing was untidy, kicking up too much dust. So, back to the drawing board it went for a design correction. Then, the scope of the mission itself was expanded, and the payload became so heavy that the launch vehicle had to be changed from a GSLV-II to a GSLV-III, which is India’s most powerful rocket.

Chandrayaan-2 is the first product of India’s expanding space vision, which is getting more ambitious. ISRO is planning a human space flight, Gaganyaan, for 2022 to commemorate India’s 75 years of independence. Soon after that, it plans to establish a Little India on a low-earth orbit, its own space station. Though still a concept, the plan is to have a station where Indian astronauts can park themselves for a considerable duration of time to conduct experiments.

Today, satellites go to Sriharikota in a state-of-the-art Satellite Transport System that protects them from earthly damages like shocks, dust, heat and humidity. The first rocket that India launched, however, was from a church ground in Thumba, Thiruvananthapuram. The young team included handpicked scientists like former president of India A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, who described the launch in his book, Ignited Minds.

Sarabhai liked Thumba, as the magnetic equator of the earth passes through it. The grounds where the church of Mary Magdalene stood were ideal for the launch of India’s first rocket, the American Nike-Apache sounding rocket. He approached the bishop for help. The bishop asked him to attend the next mass and tell the congregation of his dream. Sarabhai’s appeal to those gathered was simple and sincere. The congregation readily relocated to another village within 100 days, and India’s space programme took root. Scientists commuted from the railway station to this remote hamlet by bicycle, and even brought rocket parts on these bicycles. (Till late into the 1970s, bullock carts were routinely used to ferry satellites.) On November 21, 1963, India launched its first rocket into space, six years before the birth of ISRO itself.

The trail of smoke the rocket left behind was ephemeral. But it etched a trajectory for India’s space programme. Kalam described how Sarabhai told his colleagues that he dreamt of India having its own launch vehicle. That dream materialised in 1980, though after his death, when India successfully placed Rohini in orbit with its own Space Launch Vehicle-3.

When convincing the government to have a space programme, Sarabhai had said: “There are some who question the relevance of space activities in a developing nation. To us, there is no ambiguity of purpose. We do not have the fantasy of competing with the economically advanced nations in the exploration of the moon or the planets or manned space-flight. But we are convinced that if we are to play a meaningful role nationally, and in the community of nations, we must be second to none in the application of advanced technologies to the real problems of man and society.”

Space applications remain the mainstay of India’s space programme. It started with the Satellite Telecommunications Experiments Project (STEP) to bring informational programmes through television to remote parts of India that were then vastly undeveloped and illiterate. Today, that same vision has created NavIC handsets, which help fishermen locate shoals and get information of sea conditions. It has also helped do away with manned railway crossings, the sites of many accidents. Railway Minister Piyush Goyal recently noted that 2018 was the most accident-free year for Indian Railways.

Also read

- Chandrayaan-2: Hope dims for Vikram lander as lunar day ends

- Moon mission would be successful on 'Ekadashi' day, claims Hindutva leader

- Chinese netizens praise Chandrayaan-2, ask scientists not to lose hope

- ISRO locates Vikram lander intact, but tilted on lunar surface

- Location of lander proves orbiter functioning well: Expert

- Chandrayaan-2: Vikram traced, but re-establishing communication 'less probable'

India’s self-reliance in space has a lot to do with having to go it alone. Its GSLV programme was stalled when the US imposed sanctions and even tried to stop Russia from helping. Russia did get around to helping, but India managed to develop its own cryogenic technology in the meantime. In fact, K. Sivan had a large role in developing cryogenic engines. Russia’s exit from Chandrayaan-2 has resulted in the mission being totally desi.

While the development of space applications has seen a steady growth, deep space explorations have been piecemeal and critics say there is a lack of sustained vision. At the recent Observer Research Foundation meet on space policy, Ajey Lele pointed out the gap of 11 years between two moon missions as a case in point. “Space exploration is one area where we have not really flexed our muscles, but could perhaps do it once national priorities change,” he said.

With plans for a Venus mission in the near future, as well as the solar probe Aditya to be launched next year, perhaps the change is happening. Fifty years on from Neil Armstrong’s moonwalk, India is getting ready to make its footprint in deep space.

This is important not just for national pride, but to be among the pioneer nations to establish outposts out there.