What is the most interesting thing about Usain Bolt? Is it that he's the world's fastest man, and the highest-paid athlete in the history of track and field? The star of the Beijing Olympics is already the megawatt draw for London 2012. He is the most famous Jamaican since Bob Marley. He lives in a five-bedroom villa in the hills above Kingston and sleeps with a healthy stack of condoms beside his bed. All of which is interesting, but.....

What about the fact that he believes he is good enough at football to play for Manchester United? Or that he is obsessed by dominoes, and he will only watch tennis if Roger Federer or the Williams sisters are playing? Or that he owns six cars—a Honda Accord, a Honda Torneo, a BMW 335i, a Nissan GTR Skyline, a Toyota Tundra truck and an Audi Q7—and that all of them are black? No, none of these is the most interesting thing.

It is a warm Sunday afternoon in Kingston, and I am sitting in a luxury suite of the Spanish Court Hotel with Bolt and five of his handlers: his manager, Ricky Simms, his personal assistant and closest friend since primary school, Nugent Walker Jr (NJ), and three high-ranking officers from Puma, his most important sponsor. Simms is sitting to Bolt's left, studying a BlackBerry; NJ is calling reception and is ordering Bolt some lunch, and one of the Puma guys is joshing with him about a recent football game and the brilliance of Wayne Rooney. "Yeah, I watched it." Bolt concurs. "He had both defenders in front of him and he just went whoosh!"

Bolt can identify with whoosh; and we are hoping he will show us some. "For me, London is going to be even bigger than Beijing," he says. "It is going to be huge. Next year is going to be so important for me." Three years ago, on a steaming hot evening in Beijing, he lined up with seven of the world's fastest men in the Olympic 100m final. He had spent the week eating Chicken McNuggets and was so laid-back as he entered the track that he forgot to tie a shoelace and was almost left in the starting blocks.

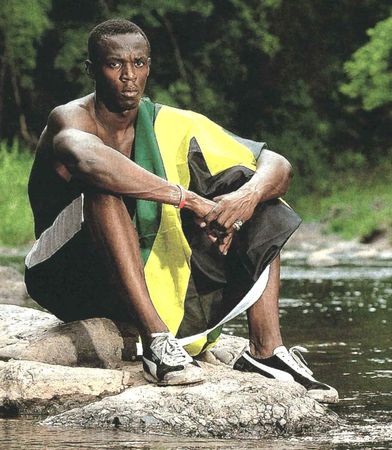

After 20m of the race, Bolt was fourth; after 50m he was level; at 55m he was pulling away from the pack; and at 85m the race was won. Bolt dropped his arms, pulled his shoulders back and coasted to the line, thumping his chest. The time was 9.69 seconds. Nobody so tall—he is 6ft 5in—had ever run so fast. In fact, nobody had ever run so fast. "I had no idea I had broken the world record," he said afterwards. "How could I have broken it? I was slowing down long before the finish and was not tired at all, I could have gone back to the start and done it all over again.” Bolt's celebration was memorably flamboyant. He continued running until he had reached the back straight, then pointed his arms skywards in the "lightning bolt" pose that has become his trademark. He hugged his mother, Jennifer, pulled a Jamaican flag from the crowd and danced for the cameras.

And the show was only starting. Four days later, Bolt won the 200m and completed a magic week in the 4x100m relay, making him the first man to win three sprinting events at a single Olympics since 1984, and the first man to set world records in all three at a single Olympics. But it was the smile and the joy that set him apart. And the facility with which he had won. He had made it look so easy!

A gentle mist caresses the hills above Kingston. It is 6:15am at the University of the West Indies and three television crews and a handful of journalists and photographers have come to Bolt's training ground. The morning is warm and gloriously tranquil, but the silence is soon broken by the roar of a black BMW, speeding down the Old Hope Road from the fashionable suburb of Norbrook.

The security guard recognises the driver immediately and there is a flurry of panic as he pulls back the gate and the cameras race for position. Bolt steers the car across the gravel and greets the reporters with a smile: "Hi everybody." He's wearing bright-yellow kit with big Puma labels and is so enamoured by the buzz as he steps from the car that he leaves the door open and the engine running.

His masseur, Everald Edwards, is waiting by the side of the track. Bolt stretches for a moment and then flops onto the massage couch, swapping patois with NJ and smiling at the cameras as his shoes and socks are removed and his muscles are caressed with warming oils. He warms up with a series of 60m shuffles down the track and stretches again until finally he is ready for work.

Gregory Little, an assistant coach at Racers Track Club, is standing by with a clipboard and stopwatch. He has four other athletes scattered around the track, but all eyes are on Bolt as he jogs to the 150m mark, settles into a crouch and opens the throttle. He moves through the gears and crosses the line in 16.8 seconds. Then he takes off his shirt, walks back down the track and does it again.

Ricky Simms, 37, joined Bolt in 2004, just before he broke the world junior record for the 200m. There were five months to go until the Athens Olympics and Bolt moved his training base to Teddington for the summer. But, Bolt was plagued by a torn hamstring and a strained Achilles tendon in the build-up to Athens, and was eliminated from the 200m in the preliminary rounds. It was a bitter disappointment and the return home was sobering.

He changed his coach, booked an appointment in Munich with Dr Hans-Wilhelm Muller-Wolfahrt, the renowned sports-injury specialist, and set his sights on Beijing. In 2005, he made the final of the 200m at the World Championships in Helsinki but pulled up with a torn hamstring. In 2006, he raced lightly and skipped the Commonwealth Games, but finished the season with promising performances at meets in Germany.

At that time, the mantle of world's fastest man was held by another Jamaican, Asafa Powell. At 24, Powell was four years older than Bolt and considerably wealthier; he had banked almost half a million dollars in prize money that season, owned a collection of fine cars and lived in a luxury villa in the hills above Kingston. His face adorned billboards across the city and convinced Bolt that he was in the wrong event.

In July 2007, Bolt persuaded his coach, Glen Mills, to allow him to race the 100m at a meeting in Crete. His winning time of 10.03 was impressive—only Powell was running faster in Jamaica—and Mills agreed that he would race the distance again. The following year, they travelled to New York and Bolt ran 9.72 seconds in what was only his fourth 100m as a professional athlete. It was a new world record. Three months later, he crushed Powell in the Olympic 100m final and broke the record again.

Bolt was two years old in 1988, when Ben Johnson, a native, like Bolt, of the parish of Trelawny, and a Jamaican until he emigrated to Canada in his teens, became the first Olympic 100m champion to break the world record for 20 years. Sixty-two hours after the event, Johnson was stripped of the medal for having tested positive for steroids. A huge shadow was cast on the sport. It lingered and grew darker every summer.

So, in August 2008, when the Lightning Bolt struck Beijing, it was inevitable there would be thunder. "For someone to run 10.03 one year and 9.69 the next, if you don't question that in a sport that has the reputation it has right now, you're a fool," the former Olympic gold medallist Carl Lewis told Sports Illustrated.

There were other questions. Jamaica had opted out of the regional arm of the World Anti-Doping Agency and had yet to establish an Anti-Doping Commission. Julien Dunkley, a member of the sprint relay team, had tested positive for an anabolic steroid a month before the Games.

But Bolt brought with him a breath of fresh air. He was the redeemer, the man who had brought the fans back to athletics. Bolt's celebrity rocketed in the weeks and months that followed. He was IAAF Athlete of the Year, Laureus Sportsman of the Year; and the youngest person ever to receive the Order of Jamaica, the nation's fourth highest honour. He was invited on the Late Show with David Letterman, went clubbing with Mickey Rourke, replaced Powell on every billboard in Kingston, and was presented with a new BMW by his grateful sponsor, Puma.

His target for 2009 was the World Championships in Berlin. In April, just as he was returning to fitness, he rolled the BMW on a wet Jamaican highway and escaped, miraculously, without a scratch. But there was trouble ahead. In July, it was reported that five members of the Jamaican World Championships team—including Bolt's training partner, Yohan Blake—had returned positive dope tests for methylxanthine, a stimulant. Bolt was not implicated but the headlines were damaging by association: "Bolt training partner fingered in drugs test"; "Bolt: I'm a clean machine"; "Bolt: My pal is OK"; "Bolt is positive about Blake's negative".

Bolt was competing at a packed Crystal Palace when the story broke: "It's sad for the sport because things were progressing well," he told reporters. "This is a step backwards. They will question everybody again now, especially people from Jamaica.... It shows that when people get tested they get caught. I'm trying my best to show that you can achieve things clean."

And what things. Bolt simply dazzled in Berlin with two world records—19.19 in the 200m and 9.58 in the 100m—and three gold medals. A year later, in August 2010, a new sponsorship deal with Puma (a four-year contract worth an estimated £21m) made him the highest-paid athlete in the history of track and field. A month after that he published his book, My Story: 9.58. There is one standout paragraph. It is this that makes Usain Bolt perhaps the most interesting sportsman in the world: "It has been said that I am the saviour of athletics, and that, having proved to be a clean athlete and smashed the world record in the flagship 100m, I've given the sport its credibility back. Equally I'm well aware that if there was ever any hint of a drug scandal against me, it could finish athletics."

What a burden, surely. "No. No it's not," he replies. "When you know you're clean you don't worry about anything. I have got to be very careful, especially if I get a cold. I don't even like taking vitamins. So for me it's not a burden because I am good. I don't have to worry about anything."

Does he keep a record of everything he takes and when he takes it? "Yes, you have got to keep records," Bolt replies. "You have got to make sure that if you take a pill and it's odd, you have to make sure you remember the name or check the package. I'll call Ricky and say, 'Ricky, could you check this out?' or whatever. Even if I am getting a new vitamin, my coach checks it 150 times to make sure everything is okay."

His handlers are getting edgy. They want me to quit this line of questioning. My time is limited, but this is important, I insist. An awkward pause ensues. The sponsors are looking at the manager; the manager is looking at me; I am looking at the world's fastest man. Bolt, predictably, doesn't have a problem with discussing the issue. "It's okay," he says.

We move on to the subject of London 2012. "I'm actually trying to refocus right now," he says, "because we've got the World Championships coming up [next month], but everything I hear is about these London Games. 'Can I get an Olympic ticket?'; 'Where can I stay?' No one is talking about the World Championships and I have to keep reminding myself to take this step first and then move onto the Olympics." Prophetic words, what with the false start and disqualification from the 100m race at Daegu, and redemption with the 200m gold.

Does being favourite change things? "Not really," he replies. "If you look at it like that, there is going to be a lot of stress on you and I try to avoid stressing myself. I am always going to be stressed by the amount of Jamaicans that are going to be in those stands. I think that's going to make me a little bit nervous. But I can't think, 'Oh, I'm the defending champion. I've got to get it right.' If I do that, I will probably lose. So, I would rather just be myself and relax. But it's going to be huge."

The morning mist has lifted from Kingston. Bolt's work has finished for the day. He abandons his spikes for flip-flops, drapes a T-shirt on his head and smiles one last time for the cameras as he shuffles towards the car: "Bye bye." The session has gone well. The Lightning Bolt is primed. But as he lights up the engine, and the black BMW screams across the gravel to the exit, his handlers are starting to sweat again. The world's fastest man is not wearing a seat belt.