Friedrich Engels stands tall on a small square by the side of the majestic Christ the Saviour Cathedral in Moscow, the seat of power of the Russian Orthodox Church. His hands folded across his chest, the Germany-born atheist, known for co-authoring the Communist Manifesto with Karl Marx, has his gaze turned away from the world’s tallest Orthodox church, where President Vladimir Putin attends mass on special days like Christmas and Easter. It is a weekend, but not many people stop to admire the Brezhnev-era bronze statue, the only monument of Engels in entire Moscow. It is strategically placed at the start of the Ostozhenka street, halfway between the Marx statue opposite the Bolshoi Theatre and the monument of Lenin near the Luzhniki stadium, a venue for the 2018 FIFA World Cup.

Across the road, at the cathedral, people continue to pour in even though the church has closed for the day. Unlike in other parts of the world, where it is the elderly who mostly populate the church, in Russia, the young come with equal fervour. The holy cross is the most favoured pendant for young women, and to be spiritual has become fashionable. “More people are now going to church regularly,” Lalita Elen Noor, a Dubai-based businesswoman from Turkmenistan, told THE WEEK. “And the Russian Orthodox Church is playing an important role in the lives of the people and their leaders. Religion, and spirituality in general, have grown since the breakup of the Soviet Union. And leaders now wear their association with the church on their sleeves.”

It is not just the Orthodox Church that is riding the spirituality wave. As much was evident when a group of Hare Krishna followers pranced around an open square in St Petersburg on a sunny afternoon, chanting and waving to passers by. Most of them were Russians, all in the prime of youth. “Many religions and spiritual movements are active in Russia and former Soviet states, such as Islam, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Mormonism,” said Lalita. “But most of them work on the periphery because of the strong presence and strict principles of the Russian Orthodox Church.”

The Church is increasingly involving itself in the life of the faithful and the government, and the people are loving it. A 2016 survey done by the Levada Center found that 56 per cent of people approved of the role played by the Church and religious NGOs in state politics. The figure was up from 42 per cent in a 2014 survey. A majority of respondents also wanted the Church to be more involved in public morality, especially in the light of the feminist rock band Pussy Riot performing songs against President Valdimir Putin near the altar of the Christ the Saviour Cathedral in 2012. Three members of the band were found guilty of “hooliganism” triggered by religious hatred (the group had gone on record saying they opposed the church’s support for Putin), and a court sentenced them to two years in jail. While the west criticised the arrest and trial, most of Russia did not agree with what the band did.

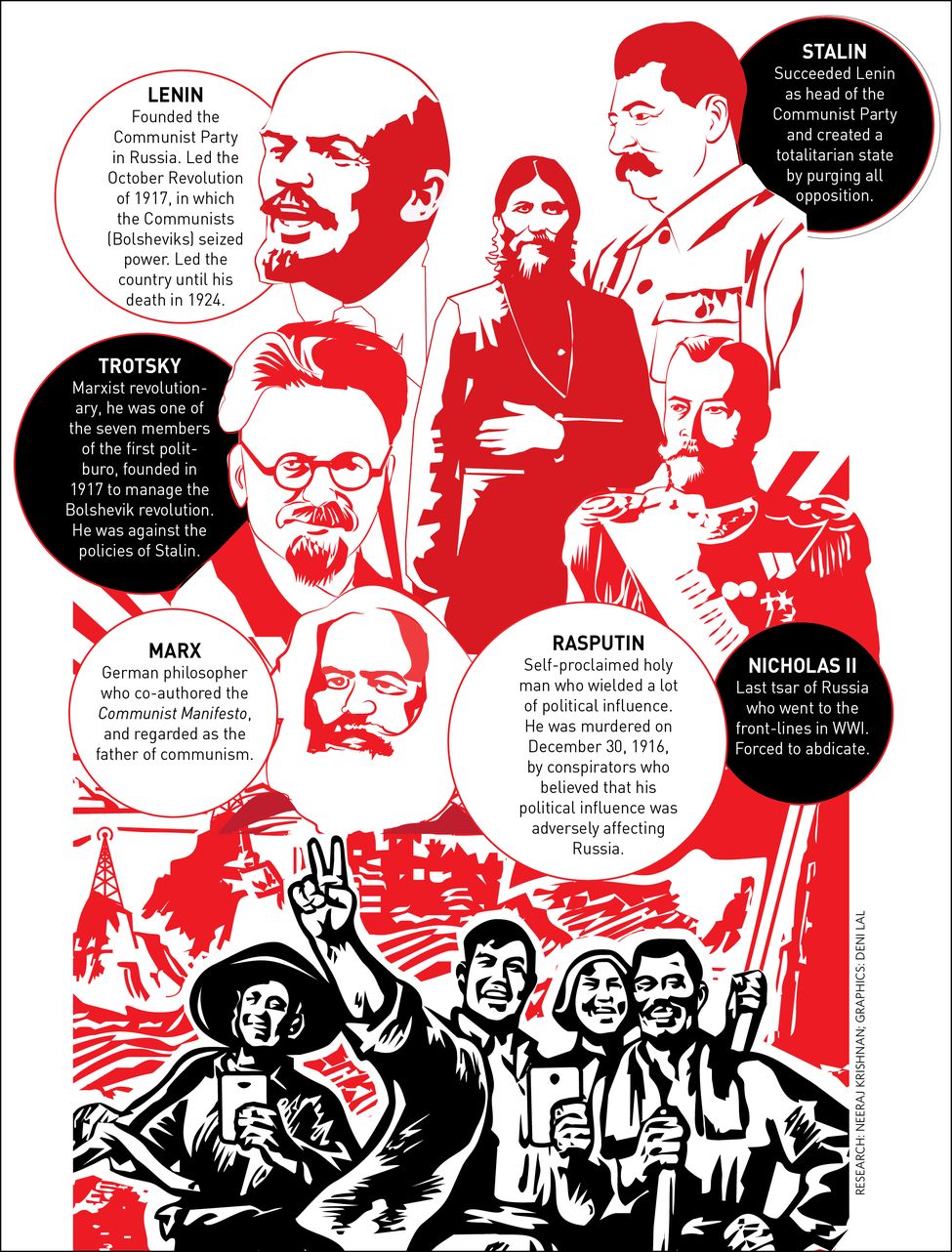

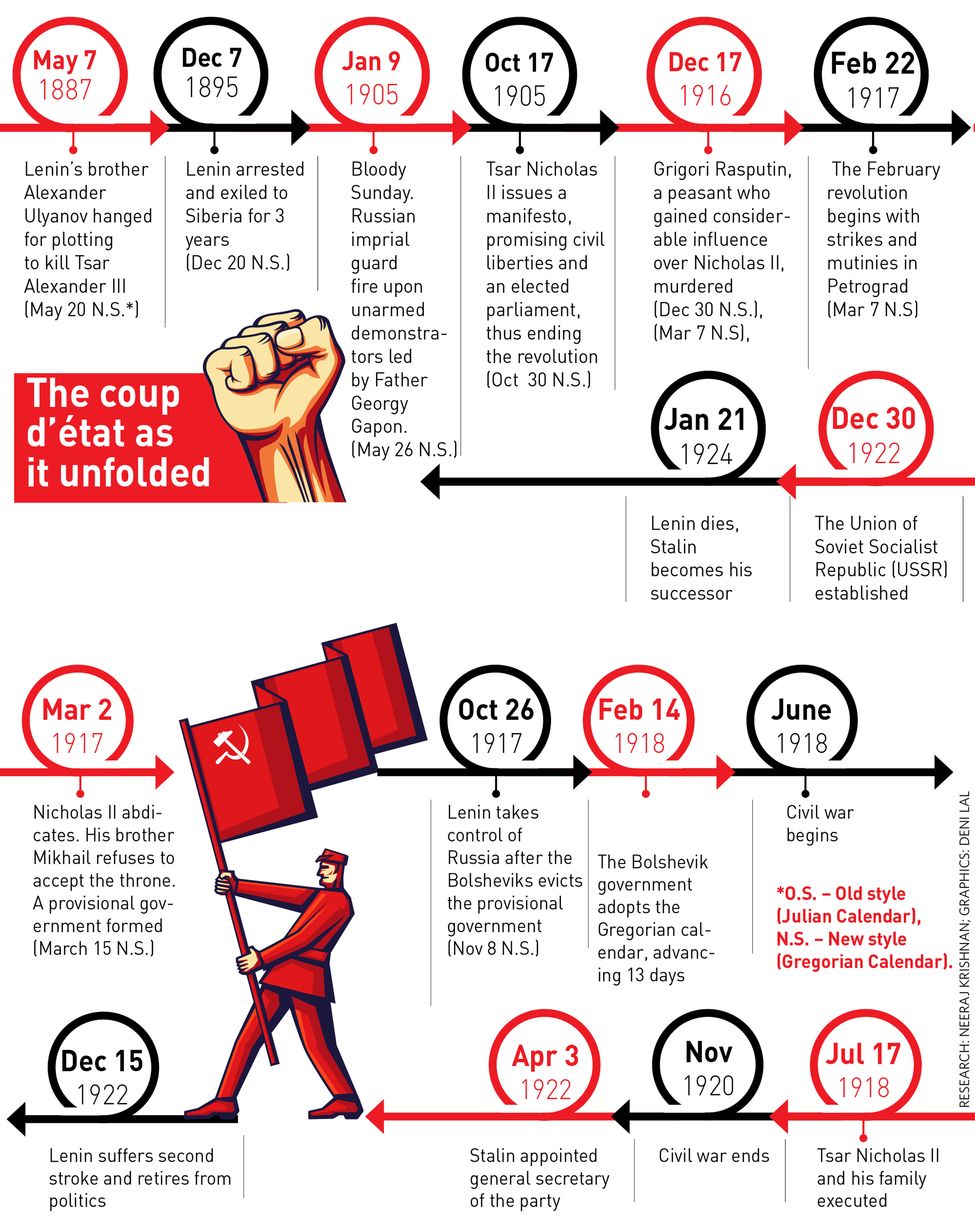

“The Church was the anchor when Russia went through testing times after the breakup,” said Dr Cherian Eapen, president of the Moscow-based firm Roy International Consultancy. “It was the glue that held the country together.” It was not a position new to the Church. Before the series of revolutions that culminated in the decisive October Revolution that saw the Bolsheviks led by Vladimir Lenin come to power, Russia ruled by the Romanovs from St Petersburg was a Christian empire. Church and the Tsars controlled lives in the vast empire. However, by early 1900, things started to change. The lame-brained decisions of Tsar Nicholas II led the empire from one crisis to another leading to a series of revolutions which saw the Tsar finally stepping down on March 2, 1917.

The Mensheviks, or the liberals, took over but the Bolsheviks, or the hardliners, were not happy with the partial change. Their quarrel with the Mensheviks led to the October revolution of 1917, which saw Lenin taking power with the help of the factory workers and peasants who laid siege to the capital, Petrograd.

Lenin became chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars or Sovnarcom, and Leon Trotsky, the commissar of foreign affairs. Decrees proclaiming reforms followed immediately. Land of the monarchy, gentry and the Church was transferred to the peasants and anti-Bolshevik press was muzzled. Workers assumed control of factories and mines and the new dispensation authorised the peasants to make their own revolutions. Russia soon slipped into a civil war, with Lenin’s Red Army battling the White Army comprising the liberals and the supporters of the Tsar regime. Two rebellions against the Bolsheviks, in 1919 and 1921, were crushed by the Red Army, and Lenin was firmly in the saddle.

Violent past: The building that once housed the KGB in Kremlin | Lukose Mathew

Violent past: The building that once housed the KGB in Kremlin | Lukose Mathew

The new constitution adopted in 1918 talked of a dictatorship of the urban and rural proletariat and the poorest of peasantry. And the centralisation of industry and agriculture began taking place. Those who resisted were crushed mercilessly, but before Lenin could take forward the dictatorship, an assassination attempt on August 30, 1918, laid him low and he died in 1924. A new constitution adopted that year proclaimed the Soviet Union as the “bulwark against the capitalist world” and said that it would mark a new, decisive step towards the unification of workers of all countries.

Post Lenin’s death, Trotsky was expected to succeed him, but the seminary-educated Josef Stalin seized control of the party and the government. Trotsky was kicked out of the Soviet Union in 1929, and was sentenced to death by a kangaroo court in the 1930s. An assassin from Kremlin tracked him down to Mexico in 1940, and killed him with an ice axe in his office.

Stalin’s reign of terror continued throughout the 1930s and 40s, and many people were executed with or without fake trials. Thousands were exiled. But, the economy boomed, thanks to the strict measures Stalin brought in to increase productivity. On October 26, 1940, he introduced seven-day working week and eight-hour work day. Coming late to work was made punishable. Under Stalin, Soviet Russia was able to stop the German war machine in World War II, with his army under General Zhukov (whose statue occupies pride of place in Kremlin, next to the eternal lamp outside the president’s palace) capturing Berlin. As many as 28 million lost their lives in the war, the most for any country.

To counter the shortage of manpower, women were encouraged to come out and work, and it inadvertently started women’s emancipation and the idea of crèches was born to take care of the children while women were at work. “It was also a golden age for learning, and Russia made great strides in technology,” recalled Andrey Arkhipov, who served in the Russian embassy in India in the 1970s. Education was made compulsory and free, and the teacher-student ratio was something like 1:10. It helped identify and channel the talent of each student. The country produced many great scientists, doctors and engineers, but most of them and their achievements remained behind the Iron Curtain. Nikita Khrushchev, who succeeded Stalin, denounced his predecessor and his policies, but the push on economy, education and technology continued.

The Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University was started in Moscow 1960 for students from friendly countries who were attracted to the idea of socialism. At one time it had students from 160 countries and education was completely free. Today, the state of the art university charges for its services ($8,000 tuition fee plus hostel and other expenses a year for the medical course), but foreign students continue to come thanks to the standard of education and infrastructure.

More than seven decades of communist rule was undone by Mikhail Gorbachev, when he pushed reforms in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics disintegrated, giving birth to several independent countries.

“I was 11 when the Soviet Union broke down,” recalled Lalita. “The principles of communism were incorporated into the education system through student unions. It started with ‘Pioneer’ movement. Officially it was not compulsory to be part of it but pretty much everyone would join in, as not being accepted was considered shameful. Students would be accepted into the organisation in batches based on academic achievements. It was prestigious to be accepted into the first batch. I can still remember the feeling when I was accepted into the first batch and wore a red necktie for the first time. Once the Pioneer stages were completed, you could join the Komsomol. The party’s representatives oversaw the activities in school.”

Back then, the October Revolution was celebrated with much fervour across the country. All major cities used to have parades and concerts. “The new generation is not even aware of the date of the revolution, let alone the details. They have adopted a western approach to life,” said Lalita. “Except for Russia, other former Soviet countries have rewritten their history books.” Russia’s communist past was erased in a jiffy under President Boris Yeltsin, the charismatic but erratic leader whose powerful oratory competed with his love for the bottle. The Americans and people from other western countries, for whom the Kremlin was inaccessible till then, were all over the place. And the Russian pride hit an all time low. “Nobody took Russians seriously then,” said Devadathan D. Nair, business consultant who came to Russia in 1988 to study broadcast journalism and has since made Moscow his home. “It was also a time when the interview with the president was sold for around $5,000.”

In the chaos, a new newspaper for the expats was launched in Moscow, and it was promoted by an entity which promoted American interests. One day, during Yeltsin’s first term in office, Nair saw an ad tucked away in the inside pages of the newspaper, asking people who were interested in having a tour of the newspaper to call the number given with the announcement. A woman took the call and asked Nair to report at the metro station close to KGB headquarters with $40.

When he got to the station and joined the group, he realised that he was the odd one out: the rest were all Americans. They were taken on an extensive trip of the once-dreaded KGB headquarters. “When we were taken to the room from where KGB chief Yuri Andropov used to control and destroy lives in Soviet Russia, an American sat on Andropov’s chair, put his feet on the table and asked his friend to take a few snaps,” recalled Nair. The building had high ceilings and every room looked alike. “It was cold and colourless,” said Nair. “The KGB suffered during Yeltsin’s time. Many of its officers left the service and joined private enterprises. Under Putin, the FSB (KGB’s new avatar) has regained its lost glory.”

To outsiders it might seem like the Russians were going through decades of oppression, but old timers in the country would disagree. “My grandparents are nostalgic about communist Russia,” said Daria Pavlova, a postgraduate in media studies. “They say we had one of the best education systems in the world, that the discipline was better and students used to respect teachers. My grandmother was a scientist.”

Her parents do not have the same view of the system as they were caught in the whirlpool of change. “My parents were engineers and they lost their jobs post the transition,” said Daria, who is based in St Petersburg. “They soon adapted to the situation, but not many were as fortunate. My father now runs a company that renovates apartments.” Those were tough days, recalled Nair, with people queuing up for hours for bread and meat. Many professionals were rendered jobless.

The people of Daria’s generation have moved on. And Russia has also recovered under Putin, whose popularity is at an all time high as he is set to face the electorate yet again in March. “The Communist Party is a part of history and let it be so,” said Daria. “Among friends we discuss politics, but only a few follow the party.” According to Anastasia Kasatkina, who had been to India in search of spiritual solace, most Russian youth are apolitical. They embrace religion or spirituality, she said, more for a feeling of belonging and camaraderie than anything else.

Anna Benedictova, a postgraduate student of Indian literature at the Lomonosov Moscow State University, said her generation was aware of the revolution as they were all proud of their nation’s history. “But I did not know that it was the centenary year,” she said. “How one views the revolution and the communist regime is based on one’s personal experience. If your close relatives had to suffer under the communist rule, I am sure you will have bad memories about those times. But no one can deny the fact that back then people had more social benefits, and patriotic feelings were stronger. People had an ideology to live for. They probably lived a better life. In today’s Russia, the gap between the rich and the poor has widened. Some people hardly make a living while a select few bathe in luxury.”

Under the communist rule, Russia was healthy, said Anna, and the nation excelled in sports and games. Education and medical services were free. “If the older generation feels a bit lost, we cannot blame it,” said Anna. “But, socialism is far away from us. We are free, can travel the world and are loving it.”