Sirte—Islamic State’s Libyan headquarters—has been reduced to a silent mass of rubble. Nothing but bad memories remain.

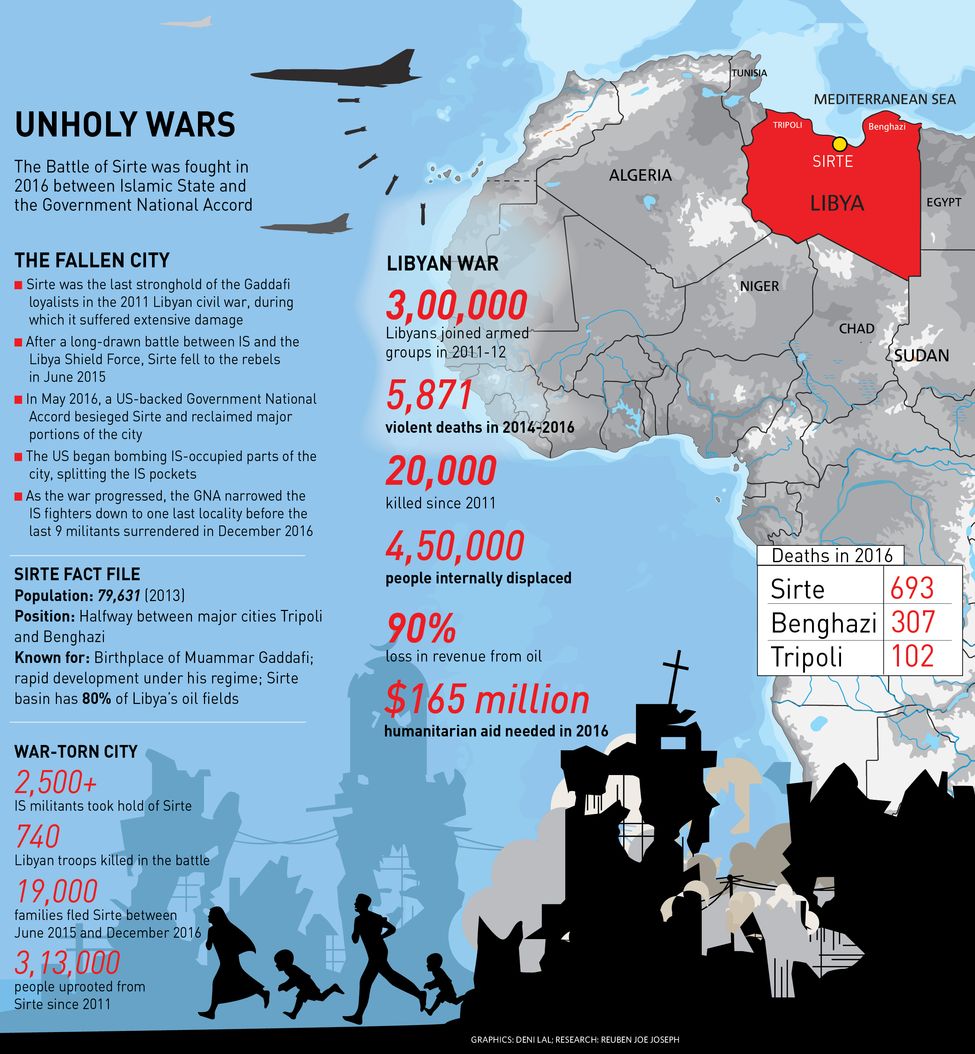

Near the Zafaran roundabout, where until a few months ago IS leaders had publicly hanged and beheaded people, the streets bear scars of the intense battle that saw US-backed Libyan forces retake the coastal city (see graphics).

Homes, banks, mosques and hospitals lie razed, even as residents cautiously return to the city. Some shop walls still bear IS stamps for tax collection. The road to Ouagadougou Conference Centre has two IS billboards. While the first one is an invitation to pray, the second depicts a Kalashnikov, and declares: “If you betray us, you are betraying your family.”

The bloody battle has left hundreds of families betrayed.

During the final cleansing operation, General Mohammed al Ghasri, spokesman for the Libyan offensive, said more than 2,500 corpses of IS militants were found in the rubble.

Most of them—Tunisians, Iraqis, Nigerians and Libyans—died young.

Documents from their bodies show years of birth as 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988....

Mohammed Malouf is a young Libyan soldier who lost many comrades-in-arms in Operation Al-Bunyan al-Marsous, better known as the Battle for Sirte, which lasted from May to mid-December last year.

“They [the militants] were young guys like us,” says Malouf. “I cannot understand how it is possible for a young man to blow himself up in the name of a corrupt interpretation of Islam. Our God does not want this.”

Scarred, scared: In a Sirte field hospital, a doctor distracts a wounded child, while another tends to her. The prolonged fighting has left children famished, dehydrated and disoriented.

Scarred, scared: In a Sirte field hospital, a doctor distracts a wounded child, while another tends to her. The prolonged fighting has left children famished, dehydrated and disoriented.

Malouf says he was scared, especially during the final weeks of the battle, as the IS militants were ruthless to the extent of sacrificing their own families to kill Libyan soldiers.

“We were not trained like them. Also, we lacked equipment; many of our guys went to fight wearing slippers,” he says. “The IS militants fought as if it was a blood sport; they were merciless.”

The Libyan army’s strategy regarding IS militants was clear from the start of the offensive: “No prisoners, finish them all.”

In Sirte alone, hundreds of militants were executed, often in haste. “It was not worth taking them to jail,” says a Libyan soldier, who does not want to be named. “It was better to kill them, and leave them under the rubble.”

The policy, however, was different when it came to the militants’ wives and children. They were not to be harmed. But now, the problem lies in differentiating between civilian and IS families, especially the women. Some of these women, soldiers say, could be dangerous.

Another young Libyan soldier, Mofth Ali, recalls one such ‘deadly’ woman. “We saw her walking towards our team with a baby in her arms,” he says. “We promised help, and told her to give us the baby first. She stretched her arms out to give the child, and then blew herself up. Four of our men died and 20, including me, were injured.”

Courage under fire: Libyan soldier carrying a colleague wounded in a booby trap set up by IS militants.

Courage under fire: Libyan soldier carrying a colleague wounded in a booby trap set up by IS militants.

Abdalh Ahmed recalls a similar shocker. “One day, as a woman with a baby walked towards our position, a sniper shot her dead,” says the Libyan soldier. “The child sat crying beside the dead mother, but we could not save him, as we, too, would have been sniped at. It was a trap; they wanted to use the baby as bait.”

Ali al Zawhiri, who specialises in mine clearance, cannot forget the rants he heard in an ‘IS house’ his team had marked. “The militants were threatening their own petrified families: ‘Shut up or we will kill you.’ It was terrible,” he says.

Ali says he is proud about saving children from such homes, but the thought that their minds would be scarred forever haunts him.

Children, he says, are the first victims of war. “I have seen women, wives of IS militants, run out of buildings with babies in their arms, wailing out that they have left other children behind,” he says.

In one of the two field hospitals on the frontline in Sirte, Dr Walid el Hamroush treats children pulled out from the rubble.

No quarter: An IS militant being taken away on December 5, as soldiers hurl abuses and threaten to lynch him. His body, with multiple gunshot wounds, was later found at the place he had surrendered.

No quarter: An IS militant being taken away on December 5, as soldiers hurl abuses and threaten to lynch him. His body, with multiple gunshot wounds, was later found at the place he had surrendered.

One boy has a burnt face, and he screams his lungs out as the doctor tries to treat the wounds. Three girls lie on stretchers; one of them is battling for life. Another one, with an IV drip fastened to her with duct tape, has a deep wound on her back, and she wails as doctors try to calm her.

Every child around is famished, dehydrated and disoriented. “These children are in really serious conditions. We are trying to stabilise them,” says Hamroush.

Some children say they have not eaten for weeks. One girl says all that she had over the past couple of weeks was a mixture of water and turmeric.

Another victim, Roudha, seems like a dead girl walking. She has not been bathed for weeks, and the stench is so bad that the medics wash her for about half an hour.

Evidently, all these children have been traumatised by the bombings and fighting. A little girl covers her ears, trembling in fear, at the slightest noise of a door creaking open.

When doctors ask these children where their fathers are, many of them shake their heads and say: “Fighting.”

“Many of them are children of IS fighters of Libyan, Tunisian, Syrian, Iraqi and Nigerian origins,” says Hamroush. “It is hard to differentiate between children of civilian and IS families. Anyway, for us, it makes no difference—we have to take care of these innocent children.”

Dust unto dust: The body of a militant lying beneath the rubble in Sirte.

Dust unto dust: The body of a militant lying beneath the rubble in Sirte.

Eight-year-old Mohammed is on the verge of collapsing. Yet, as doctors get close to him, he shouts: “You are infidels, my father will kill you all.”

Mohammed never went to school; all his father taught him was that it was great to die in the name of Allah. “My father says all infidels should be punished and eliminated,” he says.

Khaled Zowbat, an ambulance driver, recalls rescuing a five-year-old Egyptian child recently. “The famished child told me: ‘My parents went to heaven. My father told me that the Libyan soldiers were infidels and will go to hell.’”

Zowbat says he is worried about such children. “Their fates could be real tragic,” he says.

Rescued or detained women—some of whom are mothers of these children—are also caught in a tragic situation. They are interrogated and taken to a prison at the air force compound in Misrata. Libyan intelligence officers say they need to assess which of them could be dangerous.

One of the women being interrogated is an 18-year-old Tunisian, who has a son. “I am ashamed to return home and face my parents,” she says. “My husband brainwashed me. He told me that he would fight until his death and that I should also die for Allah.”

During the final weeks of the war, IS militants forced their women to wear explosive belts. “They said it was our duty to kill and die,” says an Iraqi woman. “They said paradise awaited us, too.”

The situation in Libya is “really very serious”, says Salah Bowzareb, the emergency head of the Libyan Red Crescent in Misrata. “There is shortage of cash and supplies, including medicines, and often there is no electricity,” he says.

Misrata is taking care of internally displaced people as well as IS families. Many of them will remain in prison because they are considered a threat to the country. But the question is: what about the children?

“If we do not take care of these children,” says Bowzareb, “they are likely to grow up into terrorists.”