It rained in the afternoon of May 22 when I reached Jama Masjid, the saffron-towered mosque that Shah Jahan built in Delhi. Pilgrims resting on its steps ran down to Mina Bazaar, children ran up the steps dragging women in black, shopkeepers poked at their plastic-sheet roofs splashing rainwater. Rain in May was a surprise; perhaps Allah had willed a whole-body wash for me before I entered the mosque. I had arrived a few days earlier from Kerala, India's instep where the Monsoon says Hi in an Arabian accent. I was unconcerned about getting wet before meeting a literary goddess who had won the Booker prize for her first novel, The God of Small Things, in 1997. In any case, this wasn't the torrent of that god. “It was raining when Rahel came back to Ayemenem,” Arundhati Roy wrote in the book. “Slanting silver ropes slammed into loose earth, ploughing it up like gunfire.”

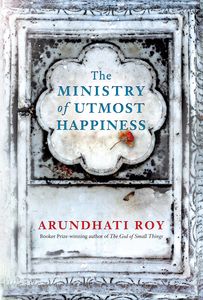

A banyan tree stood in the middle of the road like a wordless visitor in bewildering traffic. Its heart-shaped leaves quivered. Hens choked in their mesh prisons, and skinless goats glistened on metal hooks, as if imitating images from Arundhati Roy's new novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. A good chunk of this novel is set in this place, and another large portion in Kashmir. The literary world was excited that Arundhati had returned to fiction after 20 years. The publishers had set June 6 for its international release in London and there would be another feast in New York two weeks later.

Boys were sweeping the previous night's dirt into open holes along with puddles left by the rain. Sidestepping the filthy flood, Photo Editor Sanjoy Ghosh and I entered the entrails of Motor Market Gali, a grimy coil of a lane full of shops bursting with auto parts—axles, crankshafts, gear rods, pistons, bleed nipples. It was here, at The Walled City Cafe and Lounge, that I was to meet the author.

Up the narrow stairs to the lounge was an entirely different world, a haveli with coloured window-panes, plants on balconies, and rooms around a courtyard that breathed into the sky. “This was the house of Nawab Faiz Ali, who lived 200 years ago,” said Sheeba Aslam Fehmi, who stood at the counter, and offered Turkish Love Tea in a Turkish finjaan, a slender little glass tumbler that wore a silver skirt. She later revealed the recipe and said she was a Hindi writer and journalist, feminist scholar and activist of CPI(M) feathers who was doing her PhD at JNU on Muslim women's movements in India and Egypt. Her mother, she said, was a card-carrying communist in Lucknow.

On meeting her, I had picked on her first name, asking “The Queen?” in jest. And she had happily joked back about her last name, saying “Fehmi, as in galat fehmi, which means misunderstanding.” Ms Understanding, I proposed. Her son Omaiyer Fehmi, 19, political science student at Bhagat Singh College, laughed unembarrassed. It was he, she said, who had thought of turning her sister-in-law's haveli into a cafe lounge. They renovated the ruin and opened shop six months ago.

Wings and prayers: Pigeons in flight at the Jama Masjid, Old Delhi.

Wings and prayers: Pigeons in flight at the Jama Masjid, Old Delhi.

Fehmi had travelled the world with her husband and son in his gap year. “A stranger hugged me at Bangkok airport,” she said, “because I was from India, the land of Arundhati Roy!” Fehmi spoke with passion about the front cover of the new book—a marble slab on a Muslim tomb—and the blurb on the back cover, a 15-word haiku. “It touches you here,” Fehmi said, touching her heart. Suddenly, her eyes widened with admiration: Arundhati Roy had appeared.

I remembered Remedios the Beauty, the wisest woman in Macondo, who never wore clothes and ascends to the skies on a humid afternoon in the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Floating on an invisible aerobics carpet, Arundhati Roy came up the stairs, looking like the child Rahel in an adult's long skirt. As I greeted her, she mentioned a benefactor of mine, whose pet name as well as the pet name of his wife appears in her first novel. It was he who had interceded for this interview.

Varun Tanwar from Penguin Random House India ushered us into the interview room, where she took a seat near the corner of an elbow-shaped bank of tables. I was assigned a seat in the crook of the elbow, sideways from her, so I had to twist my yogic spine to look her in the face. I guessed that there was a discreet device kept under my assigned table to record the interview, for her protection in the event of any mischievous misquoting or inadvertent galat fehmi in these insidious times. On my part, I deployed three cellphones on her table to record it in my own war with gremlins. Varun sat ten feet away, in the shadows.

Arundhati, 55, was looking radiant with a halo of locks, by no means a Medusa who shouldn't be looked in the face. She seemed more like the angelic maiden that Medusa had been before she was raped by a god. But gazing at her still carried the risk of being turned into stone, I told myself, as she was an enchantress who cast an unbreakable spell with the written word, an awesome wordwitch.

I had read The Ministry of Utmost Happiness over three days, most of its 444 pages sparkling with poetic word-pictures or vengeful verbal knives that glinted like a nose-stud in artificial light. Its soul, Aftab who became Anjum, leaves her hijra House of Dreams and lives “like a tree” in a graveyard near a hospital mortuary in Delhi after a demented Gujarat “folded men and unfolded women”. She becomes a “feral spectre” (to me, a traumatised Medusa) whose loose front tooth “moved up and down terrifyingly, like a harmonium key playing a tune of its own” when she spoke.

Her music teacher Ustad Hameed sat on a grave with her harmonium and sang, to soothe her, to see her through trauma, as she sat cross-legged on another grave, with her back to him. “She would not speak to him or look at him. He did not mind. He could tell from the stillness of her shoulders that she was listening.”

As trauma abates, Anjum builds a shack in the graveyard, then adds rooms for guests, and names it Jannat Guest House. It opens a funeral parlour with the arrival of the mortuary attendant, a dalit called Dayachand who took the name Saddam Hussain after he saw his father being lynched for carrying a dead cow. I asked Arundhati what she thought of cow rakshaks. She burst out in laughter. “Cow rakshak? It is gau rakshak!” she roared with a child’s delight, and suggested that I ask Saddam Hussain. “I have no views different from Saddam,” she said.

Dust, ashes: ‘Martyrs’ Graveyard’, Srinagar | Umer Asif

Dust, ashes: ‘Martyrs’ Graveyard’, Srinagar | Umer Asif

Several other tormented souls flock to the Jannat. Some are Anjum's old hijra friends, and a new one called Ishrat-the-Beautiful comes visiting from Indore. Ishrat and Saddam watch Anjum vanquish Aggarwal the Accountant in a spectacular contest at Jantar Mantar where an old man with a baby’s voice is on a fast against corruption. Arundhati makes little effort to camouflage Arvind Kejriwal or Anna Hazare, or the prime ministers she lampoons: the poet of long pauses, the Trapped Rabbit and Gujarat ka Lalla. But was it fair to refer to Kejriwal by his caste, I asked the author. “There are thousands of Aggarwals in Delhi,” she said, sticking to the disclaimer that all characters are fictional.

Anjum seems a ferocious avatar of Arundhati herself, an anguished emanation of the writer's tormented soul, raging against power and authority, pulling down borders of all kind and seeking infinite justice.

More evidently, Arundhati is Tilottama, the dark illegitimate daughter of an untouchable man and a Syrian Christian woman who abandons her and recovers her later, but raves against the untouchables in her old age. Like Rahel, Tilottama goes to architecture school, likes owls and roosters, and falls in love with a fellow student—her lover Musa Yeswi from Kashmir later joins militants. In public they behave as if they are siblings. Tilottama's mother is Maryam, which is the name of the mother of Musa in the Quran, but when I asked Arundhati about any hidden connection, she said no. I was more intrigued by the surname Yeswi, which Kashmiris pronounce as Esavi, meaning Isa’s. It hinted at another spiritual thread in The Ministry of Utmost Happiness.

Perhaps Arundhati was becoming a mystic like Hazrat Sarmad Shaheed, the naked fakir who defied the emperor Aurangzeb and, when beheaded, sang on with his severed head in his hand. “How can I possibly be saying such a thing about myself,” Arundhati said. “I am not a hazrat of any kind. He is a beautiful hazrat. I would like to talk about him more than about myself.”

She was perhaps a poet trapped in a prose-prophet's ink-pot, a literary transperson, a hijra at heart. She warmed up to it. “I think all writers should be literary transpersons, who don't accept any rules about how they should be writing,” she said. “And why should there be any sharp border between prose and poetry.”

Comparing her literary evolution to the poet T.S. Eliot's, I said The God of Small Things was like The Wasteland with its broken images, a story of intense personal pain and confusion, and difficult to understand. “Is The God of Small Things difficult to understand?” she interjected in surprise. I said its structure made it difficult to grasp at the first reading, and said The Ministry was simpler, universal and spiritual, like Four Quartets, for which Eliot received the Nobel Prize.

I embarrassed her. “No, I can’t really compare myself to…,” she said, but admitted that there was a shift in her style, because she did not want to write the same book again. “The Ministry is a novel experiment,” she said.

Spiritually political. The Jannat becomes a commune of hijras, dalits, Maoists, Sufis, orphans, animals and animal lovers. It has shades of a political experiment, like Lalu Yadav’s Muslim-Yadav combination in Bihar or Siddaramaiah’s AHINDA in Karnataka. “It is not a political experiment,” Arundhati insisted. “It is the culmination of a story. As Saddam says in the book, it is the tide that has brought them here. Many of us who are not with the mainstream hindutva project are being pushed into a graveyard. This is not the metaphor for anything; it is not that I started with a theoretical, satirical or ironical point. It is a logical conclusion to what happened to these people and why they ended up there.”

Undead voice: Tomb of Hazrat Sarmad Shaheed, who was beheaded by Aurangzeb.

Undead voice: Tomb of Hazrat Sarmad Shaheed, who was beheaded by Aurangzeb.

Was she saying that utmost happiness, an ideal world, could be found only in the company of the dead, in the graveyard? “It is the opposite,” she said with vehemence. “In that space of the dead, the border between life and death is also being challenged. It is not a submission to death. They are standing their ground and living their lives.”

Though the novel is also a story of chamars, it makes no mention of their leader Mayawati, her pearls or elephants. “She does not have a big presence in Delhi,” Arundhati explained, weakly. “It is not that kind of a book anyway.” Similarly, it largely ignores the northeastern insurrections; no nod to the naked mothers of Manipur or the nasal tubes of Irom Sharmila. “What you are suggesting is that I should have started off with some kind of reservation chart,” she said, making me laugh out loud.

I had a hypothetical question: Whom would she admit into the Jannat if there was room for only one, Rohith Vemula or Kanhaiya Kumar? “You will have to ask Anjum,” she said, cheerfully. “You know, she is very irrational, but I am sure she will admit both.” I did not tell her that I was addressing Anjum at that moment.

But then why didn’t Arundhati admit Musa into the Jannat? “You killed him,” I said. “You are the author, you could have kept him on.” Arundhati said, “Musa would not want to live in the Jannat, even if he was not dead. He does not live in India. He does not feel that that is his home.”

Towards the end, The Ministry reads like a racy thriller, I pointed out. “I don't read thrillers,” she said. “When you are writing about places like Kashmir, it informs; the killings undercover. But I realised recently, after writing this book, that there was something similar about The God of Small Things’ ending, too—the policemen on the boat.” She realised it while reading the audio book of her first novel.

I mentioned writing rituals—Ernest Hemingway used to stand and write whereas Truman Capote lay down for it. She said she had no such quirks. Writing, she said, was not about putting a word into a computer or into a page. “I am writing all the time, when I am cooking, when am walking on the street, whatever I am doing. There is no holiday.”

People say Arundhati is the voice of India's conscience and deserves the Nobel Peace Prize, if not the Literature Prize. So, I asked whether she would accept the Dynamite Prize. “I am not the voice of people,” she said. “I am a writer. I write my own stuff.” Her tone was cutting edge. “I do not wish to speak on behalf of anybody. I am not a politician. I am not representing anybody.” She giggled when I said, “Yes, you say you are a republic.” But she admitted that she had once voted in an assembly election in Delhi. “I have never voted in my life,” I declared with undemocratic vanity.

Bound by blood: A butcher’s shop.

Bound by blood: A butcher’s shop.

Democracy sleeps on military’s chest. The ruthless Major Amrik Singh in the book does his bit for it in Kashmir with all his organs. “You cannot say he represents military,” Arundhati corrected me. “That would be a wrong thing to say. He works in the military. He is a product of a system that requires no accountability. He has the infrastructure of impunity.”

She said most soldiers were not like him and did not go off the rails, although certain amount of cruelty was part of the job of maintaining military administration of a resentful population.

One of the important things about this book, she said, was that there were human and animal characters in it. “Normally much of the time you have either animal books or human books. Even though The Ministry is set in cities it has so many animal characters in it… owls, vultures, goats, cats, dogs, horses, dung beetles.”

She did not see any contradiction in having a kinship with animals and eating meat. “We are part of a world where animals also eat each other,” she said, making me, a vegetarian by choice, chortle. “The problem is when vegetarians think human beings are not part of this web of life, that they are separate, that they can destroy the habitat for retaining their pure vegetarianism.”

Along with birds, animals and insects, the souls in the graveyard try to erase the border between the living and the dead. Anjum banishes an old demon from her mind, and perhaps finds utter happiness, when little Miss Jebeen pees under a street light and lifts “her bottom to marvel at the night sky and the stars and the one-thousand-year-old city reflected in the puddle she had made”. Jebeen is an interesting name which means beautiful forehead in Urdu and the river Ganga in Persian. It also reminds me of earth and hope.

I saw the book as an epic satire, but the author would not agree. “I think it has some satirical humour, but it isn't a satire,” Arundhati insisted. I had also heard an Orwellian chuckle in the book’s title, and seen in it a phantom of the Ministry of Home Affairs—Ministry of HA, a laugh—but it is rather a ministry of compassion, like a church ladling out happiness from its spiritual soup kitchen.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is an epic of our times, a book of voices and languages and recoveries and documents. It tells a multitude of stories through a multitude of voices, and the numerous threads and their kinks combine to make it an amazing work of art comparable to the grimy, dark and timeless lanes near Jama Masjid and the bewildering traffic around it.