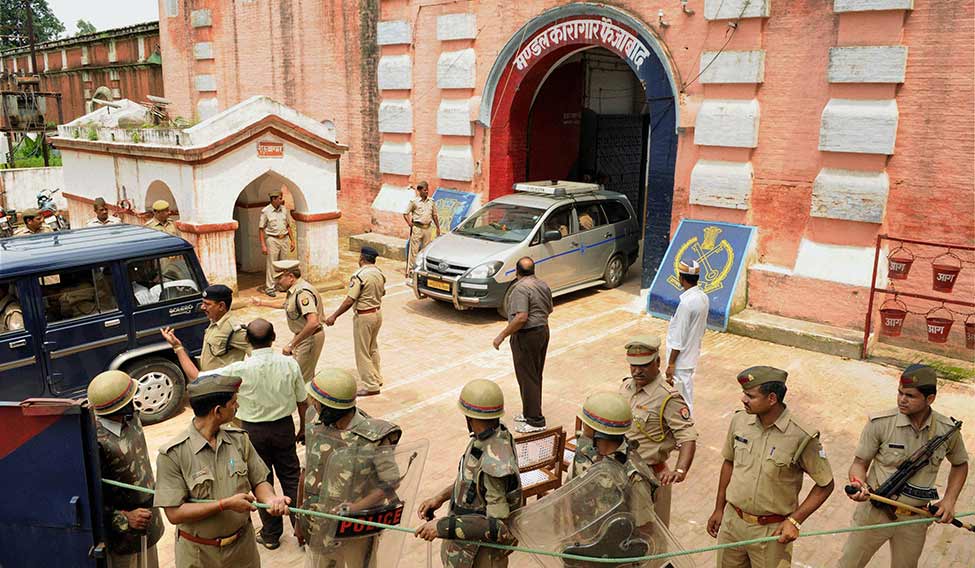

Being an additional director general or inspector general of prisons is not an easy task. Take the case of IPS officer Sushovan Banerjee, additional director general, Bhopal Central Jail, who was shunted out hours after eight activists of the Students Islamic Movement of India killed a head constable and scaled the walls of the ‘high security prison’ on October 31. Or, that of IAS officer Vinod Sharma, who was inspector general, jails, in Uttarakhand. He was removed from the post after notorious criminal and undertrial prisoner Amit Malik alias Bhura escaped from police custody while being taken to a court in Baghpat in December 2014. While his aides pepper sprayed the policemen, Bhura escaped with two AK-47s and an INSAS rifle snatched from the cops. A red-faced Uttarakhand government replaced Sharma with IPS officer P.V.K. Prasad. With Sharma’s ouster, the 14-year-old tradition of IAS officers holding the post of IG, prisons, came to an end.

The IAS-IPS debate for handling prison security hots up after every prison breach or jailbreak, but when something in Indian administration gets rotten, there is little any one officer can correct. This time, it is prison reforms. It would be unfair to say nothing has been done on this front. Ironically, the huge amount of work that has gone into prison reforms has remained merely on paper. It has been more than a decade since the Central government rolled out the ambitious modernisation of prison scheme, spending crores for assisting states grappling with poor infrastructure in prisons, overcrowding, congestion, increasing proportion of undertrial prisoners, lack of prison staff, inadequate implementation of correctional measures and above all, building additional security infrastructure through technological upgrade like CCTV cameras and sensors.

The scheme witnessed a slow death. In 2012, the expenditure department of the finance ministry was not in favour of the scheme. It observed that the scheme is predicated upon the premise that states do not have sufficient funds. It was argued that not only had the 13th finance commission (2007-2012) provided funds for prison infrastructure, but earlier finance commissions had also provided funds for the same.

The Central government had been providing financial assistance to the state governments in this key area of criminal justice system since 1987. Between 1987 and 1992, Rs 45 crore was released to all states under the non-plan scheme for ‘modernisation of prison administration’. From 1993, the scheme was converted into a plan scheme and in the eighth Five-Year Plan (1992-1997), an outlay of Rs 100 crore was mentioned. In September 2002, the Union cabinet decided to set aside Rs 1,800 crore for five years.

But the money drain has not kept pace with the impact of the scheme, which ran over two phases. “In some states, after construction of buildings for jails, such buildings have not been put to use as prisons but have been handed over to some other departments. Many others have not even been operationalised,” says a 2014 home ministry report on the impact of the scheme.

The impact of the scheme was separately evaluated by Ernst & Young in 2012, which got buried in the files of the Centre-state division of home ministry. It was observed that most of the prisons undertaken for the study are still overcrowded. Most prisons require internal roads and lighting within its compound. Live-wire fencing is required in some prisons where the height of the perimeter wall is less than 21 feet. Open sewage and drainage network in many prisons needs to be upgraded to concealed underground system. There is an acute shortage of staff across prisons, which is a key concern for smooth functioning of prisons. It further said additional security infrastructure was required to reduce reliance on extra guards and to increase vigil during working hours. Technological upgrade needs include CCTVs, walkie-talkies and video conferencing facility.

The home ministry, which has been monitoring the performance of states, stressed that the funds were supposed to be spent on construction of perimeter wall or increasing the height of the perimeter wall as per specification of the Model Prison Manual, installation of different levels of security infrastructure in terms of body scanners, mobile phone jammers, CCTVs covering all important areas of the correctional home with video analytics and automatic alerts.

On paper, the states submitted proposals on how they were going to spend the money. As much as Rs 13,962.59 crore was projected in documents submitted by 29 states and Union territories under various heads in 2009. Madhya Pradesh gave an estimate of Rs 547.83 crore, of which Rs 342.76 crore was meant for improving the security of prisons.

What continues to remain in the records of the Central government are ‘Best Practices in Correctional Administration by Madhya Pradesh’. In its list of best practices, there is incoming telephone facility for prisoners, improved prison visiting system, 42 days parole for the prisoners, an open jail colony at Hoshangabad and skill development programmes. There is, however, no mention of prisoner and prison security.