“Caught in emotions, she walked on unaware....waiting in ambush, a wolf lurked somewhere”.

The above lines could have been written for the 19-year-old from Hathras—allegedly raped and brutalised in the field from where she fetched fodder for her cattle.

But these lines were not written for her.

They are from a poem titled ‘Main Chamaron ki gali tak le chalunga aapko’ (I will take you to the lane of Chamars), by Adam Gondvi, a poet who wrote of dalit oppression and corrupt politicians.

In the picture that Gondvi (born Ram Nath Singh) paints of the sweltering dalit life, the search for justice is futile. As far as the template of crimes against women in Uttar Pradesh goes, this is eerily familiar. When caste, power and politics are coded into that pattern, a toxic pit emerges. And justice is buried in its depths.

The brutal injuries, the shifting between hospitals, the death, the hurried cremation, the threats, the blocking of access, a frenzied media and a political maelstrom—there are many offshoots of the Hathras crime.

In its root lies fear.

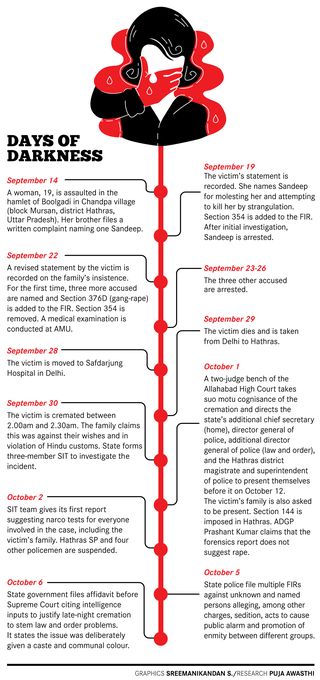

On September 14, the girl’s brother gave a handwritten complaint to the local police station at Chandpa, the village of which their hamlet is a part. It said that the siblings had gone to the millet fields with their mother. When the brother made a trip home to offload a stack of hay, one Sandeep tried to kill his sister. Read the complaint: “She shouted and my mother responded, ‘I am coming’. Upon hearing the voice, Sandeep ran away. The incident occurred around 9.30 in the morning.”

At 10.30am, this complaint was converted into a police report. The sections applied were 307 of the Indian Penal Code (attempt to murder) and section 3(2) (v) of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities Act), 1989.

The victim was from the Valmiki caste—a people who have traditionally worked as sweepers and scavengers. The kind whom Gondvi’s poem describes thus: “Standing up to Thakurs, they think is child’s playì Such rascals have their bearings not at home, but in jail.”

Sandeep and the other three accused—Luvkush, Ravi and Ramkumar—are Thakurs.

On September 19, senior Congress leader Shyoraj Jivan Valmiki visited the victim at the Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College in Aligarh Muslim University, where she was admitted after primary treatment at Hathras’s district hospital.

“The family was scared,” said Valmiki. “The girl was in pain. Custom demanded that I do not speak much to her. But to the father and brother I said, speak the truth, do not be scared, we are all with you. They said she had been raped, but their hesitation over not mentioning it to the police was understandable.”

After that visit at 3.30pm, Valmiki called the investigating officer. He was told that the victim’s statement had been recorded at 12pm the same day (September 19) and no mention of rape was made. On September 22, in another statement, the first mention of rape and four assailants was made.

The medical report from AMU noted, “Opinion regarding penetrative intercourse is reserved pending availability of FSL (forensic science laboratory) report”. It added: “No secretions present 8 days past assault.” The forensic report read: “There are no signs suggestive of vaginal/anal intercourse. There are evidences of physical assault (injuries over the neck and the back).”

These reports that the state has cited to bolster its ‘no rape was committed’ claim are legally tenuous as a dying declaration overrides medical examinations that negate rape.

Rajkumari Bansal, a forensics expert from the Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose Medical College, Jabalpur, said, “Medical reports can be manipulated. It is foolish for the government to believe that people will accept its version.” Bansal stayed with the victim’s family for three days, driven by her desire to “prevent dalits from being systematically prosecuted”.

The victim’s brother said, “I was terrified for my sister. She lay in blood without the clothes on the lower part of her body. I just wanted the police to help us get her to a hospital. But they said they would not do it without a written complaint. So, I scribbled something on a paper, adding towards the end our caste.”

A pervasive fear of the police is commonplace in Uttar Pradesh where law and order lumbers to the tune of politics. During the previous regime of the Samajwadi Party, Akhilesh Yadav’s caste peers were stationed on all posts that involved direct contact with people. Thus, justice or its absence reflected this preference.

Under Yogi Adityanath, the man who compared women to unbridled energy that needs control lest it turn dangerous, the police seem unconcerned about crimes against women. When those crimes are against the poor from backward castes, dalits or minorities, they matter even less. And when the state acquires for itself an unaccountable, unquestionable right to search and arrest without warrant through a special force (called the Uttar Pradesh Special Security Force), the fear grows deeper.

Earlier this year, a report titled Barriers in Accessing Justice chronicled the experiences of 14 rape and gang-rape survivors in the state. Authored by the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative and the Association for Advocacy and Legal Initiatives, the study noted, “Survivors faced delay, derision, pressure and severe harassment when they approached the police to report complaints and seek the registration of a first information reportì (They) faced discrimination by the police on the basis of gender and caste, impeding their access to justice at the gateway to the legal system. These experiences amplified the trauma of survivors and affected their mental and physical well-being.” For the marginalised, these burdens are heavier.

The 2019 report of the National Crime Records Bureau counted 11,829 crimes against SCs and STs in the state. This accounts for more than one fourth of all such crimes reported in the country. On the charge of assault on modesty of women from these communities, the state beats all others. It also has the highest number of cases being tried in courts for all crimes against SCs and STs.

In the victim’s village, the Thakurs and Brahmins are more than two and a half times the SCs. But these upper castes are petrified by the hostile glare of the media and the politicians.

Yogendra Singh Gehlot, the Hathras president of the Akhil Bhartiya Kshatriya Mahasabha, one of the organisations speaking for the hamlet’s Thakurs, said, “This case is born out of personal enmity. The victim’s family has been swayed by political forces. All we demand is a fair probe—through whichever agency.”

Said Ramkumar’s father, Rakesh (he uses just one name): “Daughters have no caste, they are saanjha (shared). So, this is a crime against my daughter. The police say my son committed it. He is a quiet boy who keeps to himself. At the time of the crime he was at the dairy plant where he works. Check the attendance. If we are lying, hang us all. But do not threaten us in this manner.”

His most pronounced point of reference is the Bhim Army. Its volunteers are rumoured to be lying in wait around the village, ready to attack when the police presence is thinner and the attention quieter.

Vinay Ratan Singh, the national president of the Bhim Army, said that his organisation was interested in ensuring justice, not in fomenting trouble. To a question on why they had chosen to focus just on Hathras, Singh said, “This case deserves particular condemnation, but we go everywhere such cases are reported.”

That everywhere includes Balrampur, where on September 29, a 22-year-old dalit woman was assaulted and allegedly gang-raped. A case just as horrific but one that did not tug at our conscience as sharply. (The state government has since assured the family of quick justice).

Uttar Pradesh is strewn with such crimes that are forgotten by those who Gondvi calls “the contractors of religion, culture and moralityì the ministers in states and the government centrally”.

In the state’s capital, on September 29, a 19-year-old dalit girl, after much dissuasion by the police, filed a report alleging that she had been kidnapped and repeatedly raped by two named and other unnamed persons. But no political or other indignation followed.

Even cases that provoke anger, fade into oblivion.

On December 5, 2019, a 23-year-old woman was set ablaze in Bhatan Khera, a hamlet in the Bihar block of Lucknow’s neighbouring Unnao district. Five Brahmin men were accused of the crime. The victim, who also alleged rape, belonged to a caste of blacksmiths. Four days later, the state’s law minister announced the setting up of 218 fast-track courts, of which 144 were to hear rape cases.

Yet, the victim’s family waits to record its statements. On October 2 this year, the deceased’s six-year-old nephew went missing. Her family lodged a case of kidnapping, naming, among others, three relatives of the earlier accused.

“We have been shunned by almost everyone in the village,” said the victim’s father. “They say we became greedy after my daughter’s death. They will not even talk to us for fear that we will complain to the police. But we are powerless people. Justice is not for us.”

In Gondvi’s hamlet of the oppressed, a space that subsumes all of the state, this is expected. For, after all, it must be wondered, “what the world has come to the one beneath our feet till yesterday, have arisen today.” And that must not be permitted.

(Gondvi’s poem as translated by Lucknow-based activist Sangita Jaiswal.)