During summer, the British rulers of India used to climb up the mountains to the comfort of Shimla in Himachal Pradesh. That class of rulers has vanished, but the post office that used to serve them at Shimla Mall still exists; though more as a stunning timber-made landmark. Written on a copper plate above the entrance of the post office is the date of inauguration of the building: 1883. India had begun changing by then. Calls for self-rule were growing, and the Indian National Congress was just two years away from its formation.

One among Shimla’s Englishmen of that era was Rudyard Kipling, who became the towering chronicler of colonial life in India. He left an indelible imprint of the days of the Raj in Shimla, the Himalayan headquarters of the British. India’s colonial rulers had built several “hill stations” like Ooty in Tamil Nadu, Shillong in Meghalaya, Matheran in Maharashtra and Murree in Pakistan, but it was Shimla alone that had the distinction of becoming the “summer capital”.

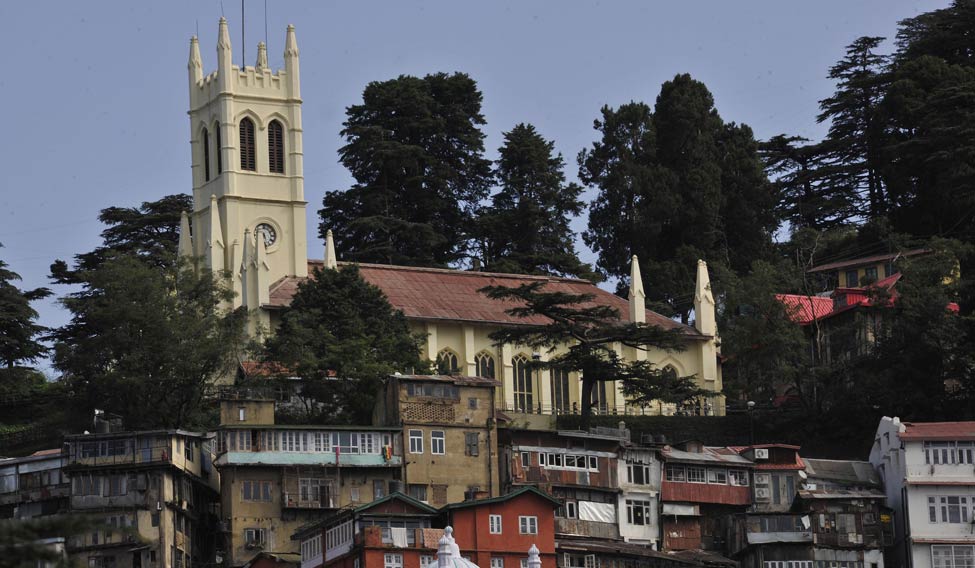

Kipling, who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1907, immortalised the Shimla of deodars, the imperial-era post office, red-painted St Andrew’s Church and timber bungalows with fire places. In his short story collection Plain Tales from the Hills, he writes that Shimla (or Simla, as he called it) was the venue of private garden parties, tennis matches, picnics and rides. He found the place throbbing with opportunities of adventure, including that of the romantic kind. His portrayal of life in Shimla often hinted at scandals and petty rivalries that erupted in the small, cosy club of the British elite that ruled the country.

As an Englishman living in the hill station, Kipling brought the inside view of the British Raj. He also had a keen ‘outsider’s eye’, which helped him observe the European hijinks in Shimla with humour and compassion. The fact that he was born in Bombay to Alice and John Kipling in 1865 perhaps helped him gain that ability. Kipling senior was head of the department of architectural sculpture in Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School of Art. As a child, Rudyard was educated in England, but his parents summoned him to India when he turned 17. He landed the job of a journalist and travelled to different parts of the country before returning to the west in 1889. By the time of his departure, he had written a great deal about Shimla and its colonial culture of patronage, fun and administration.

More than a century later, Shimla continues to be known as the Queen of the Hills. But the unregulated construction boom that took place after Independence has marred its reputation―a reason journalist Archana Phul called the city a “Himalayan slum”.

A view of the city from my hotel room projects the chaotic vision of Shimla rather than its heritage town tag. Though the Mall, with its colonial era structures and churches, is on top of the town, the lower layers have grown with scant regard for principles of town planning.

However, not all people think Shimla has changed for the worse. Lal Singh, a taxi driver and guide, says modern amenities guarantee comfort to residents and visitors alike. “No one wants to go back to those days when basic amenities were denied to the masses. Only a handful of people enjoyed life during those times,” he says.

Singh, however, points out that the colonial era was far more eco-friendly than the present. “Rampant construction activities are blowing up sources of spring water. We have to be more respectful of the water that we have in Shimla,” he says, as we drive around Shimla Hills, which seems bursting with numerous spring water sources.

The Uttarakhand floods and landslides in June were a eye-opener for the people of Shimla. Many are now campaigning for corrective steps to be taken to save the Queen of the Hills and its legacy.

Indeed, the battle for protecting Shimla and its way of life had begun even when Kipling was a resident here. When colonial administrators took over Shimla’s finest dance hall, Kipling feared that the social life in the hill station would come to an end. He wrote in The Plea of the Simla Dancers:

Must babus do their work on polished teak?

Are ballrooms fittest for the ink you spill?

Was there no other cheaper house to seek?

….So shall you mazed amid old memories stand,

So shall you toil, and shall accomplish nought,

Give us our ravished ball-room back again.

Kipling’s fears may have been for the colonial-era revelries, but his lines find relevance even today. The 21st century Shimla is striving to strike a balance between the past and the present; between rampant urbanisation and calls for conservation.

Illustration: Bhaskaran

Illustration: Bhaskaran

SIMLA is eccentric in its fashion of tearing friendships. Certain attachments which have set and crystallised through half a dozen seasons acquire almost the sanctity of the marriage bond, and are revered as such. Again, certain attachments equally old, and, to all appearance, equally venerable, never seem to win any recognised official status; while a chance-sprung acquaintance now two months born, steps into the place which by right belongs to the senior.

―At the Pit’s Mouth, Rudyard Kipling, 1888