Khurshed is the most pampered bull in Surat, Gujarat. He does not have to go looking for food; every day, employees of the fire temple at Saiyyadpura bring him his fodder. At night, he walks into his pen, where a Pest-o-Flash guards him from mosquitoes and other flies. In exchange for his comfort, Khurshed confers blessings of the animal kingdom on the Parsis who visit the fire temple.

The temple was built in 1823, a few years before the Dutch rule ended in Surat. Khurshed is the latest in the long line of albino bulls and cows the temple has had as holy animals since its start. He fits the prerequisites for the position: he is a rare albino without a single black hair on his body, and he did not get hurt while he was ensnared and brought to the temple. “Even the eyelashes [of the chosen bull] are supposed to be white,” says Rustomji Gustadji Bathena, an expert bull-catcher in Surat’s Parsi community, which number around 3,000.

Surat has been home to Parsis since the early medieval times. Italian scholar Niccolao Manucci, who visited Mughal India during the 17th century, writes that they came in droves to Surat and neighbouring towns like Navsari to protect their unique culture. The fire temple at Saiyyadpura is one of the most orthodox in the world. Rustomji says the customs have not changed since the day their ancestors landed on the Indian coast. Keeping a cow or a bull in the fire temple is an Indo-Aryan practice that is several thousand years old. “The hair of the bull is used in a ceremony called yashna, which is similar to a yagna,” says Rustomji.

Even as they cling onto their traditions, the Parsis are very much in tune with the times. They have thrived in modern Surat, a bustling city known for its diamond trade and infectious energy. Amid the raging, non-stop vehicular traffic, the distinct spirit of Gujarati enterprise greets one in every street and alley.

The Surat Manucci saw was not very different. He came at a time when the Mughal might in India was at its peak. In Storia Do Mogor, Manucci describes how the city was dominated by orders from Delhi and Agra, the seats of the Mughal emperors. Surat, Manucci writes, was the most important port of India. He was obviously impressed by the waters of the Tapti, which allowed trading vessels from all over the known world to sail deep inland. But if Surat had emerged as an important port by the time of Manucci's arrival, it was partly because of the fact that the Dutch and, later on, the English merchants had turned it into a global trade zone on the west coast of Mughal India.

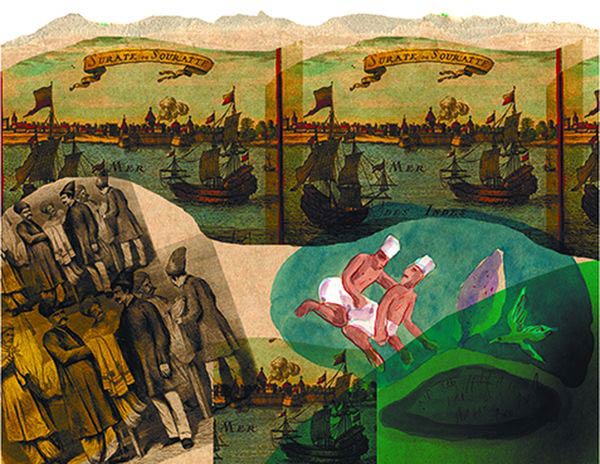

Illustration: Bhaskaran

Illustration: Bhaskaran

The Dutch left Surat by 1825, when the English East India Company took control of it. By then, European travellers and traders had given this trade outpost a unique gift: they taught Parsis the art of European bread-making. Indeed, given the spicy nature of the Indian palate, they had little choice. “They trained a small group of Parsi men in the craft of bread-making. This group soon specialised in making a whole range of European breads, cakes and snacks, which helped the Dutch survive away from home,” says Cyrus Dotivala of the legendary Dotivala Bakery in Surat, where the combined aroma of freshly-baked sweet vanilla cakes and warm golden-back bread would have a visitor drooling.

Cyrus says the Dotivalas are one of the families that were part of the original Parsi bread-makers of Surat. Over the years, they have had the patronage of a distinguished clientele. One of the patrons was Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw, who, like Cyrus, was a Gujarati Parsi. He enjoyed their famous nan khatais and cakes.

With their age-old fire temples and their bread-making prowess, the Parsis act as a link between Surat and two very different cultures: the Persian and the European. In fact, the sacred fire at Saiyyadpura glows further into the past. It was lit in 1823, from a flame that was part of a fire which is believed to have existed since antiquity.

The embers of Hindu nationalism also flicker in Surat, as evident from the numerous posters of Narendra Modi, the chief minister and the BJP's prime ministerial candidate. The party recently won the Assembly byelection in Surat West constituency by an overwhelming margin of 66,000 votes.

As for the Parsis, they continue to influence the city's future with their education and enterprise. But Cyrus, for one, is worried that despite their accomplishments, the community is dwindling because of its low birth rate.

For a change, the fire temple at Saiyyadpura has appointed a young man of 20 as the manager to inspire religious conviction among the men and women of his generation. Farzan Bagwaria's duties include nursing the sacred fire and ensuring that prayers are held five times a day. “During each prayer, I ring the bell nine times. Each sound of the bell expels evil from the human mind,” he says.

Farzan, too, hopes that young Parsis will thrive―both in numbers and in life.

Blessings, by the horns: Rustomji, an expert bull-catcher in Surat's Parsi community, with Khurshed, the bull that confers blessings on the faithful at the fire temple in Saiyyadpura | Amey Mansabdar

Blessings, by the horns: Rustomji, an expert bull-catcher in Surat's Parsi community, with Khurshed, the bull that confers blessings on the faithful at the fire temple in Saiyyadpura | Amey Mansabdar