In 2022, R. Balki made a film in which the protagonist, a serial killer, ruthlessly eliminates film critics, particularly those who “fail to see a film as a piece of art and trash it with poor ratings”. He takes the dramatic part of their film reviews as inspiration for his modus operandi, carving stars on the critics’ heads to mimic the star rating system of reviews. The first murder leaves a portly film critic sitting on the toilet, naked. His body has been slashed multiple times and his modesty protected by a roll of toilet paper. The killer, a cinephile, is also a failed director and a fanboy of the celebrated writer-actor-director Guru Dutt, and each time he murders a reviewer, he does so strategically against the background score of Dutt’s classics, including Kaagaz Ke Phool. The 1959 release, which remains one of the finest examples of self-reflection in world cinema, was famously trashed by critics of the time, only to attain cult status decades later. Dutt was so heartbroken at the film’s then failure that he never directed another movie.

Balki, in his homage to Dutt in the aptly titled Chup: Revenge of the Artist, avenges Dutt’s misery by “putting a bloody, ironic spin to the classic”. “While tearing his art apart, nobody thought about the sensitivity of the artiste. I wanted to show the world how the art and the artiste remain evergreen, transcending space and time. The ingenuity of the genius shines and inspires generation after generation,” Balki had told THE WEEK ahead of Chup’s release.

Exactly a century after he was born, Guru Dutt (July 9, 1925-October 10, 1964)—considered to be one of the greatest filmmakers—means different things to different people. To the student of cinema, he is a lengthy multi-part case study of 1950s-1960s Hindi cinema. To the cinephile in her twilight years, Dutt was the matinee idol, the brooding artiste with soulful eyes and broad shoulders. To the aspiring actor and the millennial forlorn lover, he is the tragic poet who offers the perfect masala fix of the irresistible circle of love and heartbreak. And to the quintessential filmmaker of today who makes movies for the love of his art, Dutt is a bible on how to create an unmistakable personal voice.

It all depends on which lens one uses to see him and at what period of time—he can be impulsive and thoughtful, brooding and reticent, witty and light-hearted, hard taskmaster and unforgiving perfectionist, a wild lover, a chilled-out father, a maverick and a man so possessed he forgot everything else, even family, when it came to films. But he is largely the tortured and deeply depressed genius who took to the bottle and died young. His flawless genius lay in choosing intriguing premises, mostly a slice of his own life, and dressing them with technical flourishes and sharp observations on society and its hypocrisies.

For his younger brother, Devi, 87, the only living Dutt sibling, he was a “colourful live wire” who preferred monotones in clothing. “My brother had an extensive white wardrobe,” Devi told THE WEEK in his first indepth interview on his eldest brother. If Dutt had his way, he would show up everywhere, including formal occasions, in white, but his wife Geeta Dutt, the renowned playback singer, would dissuade him from doing so at least for film premieres, insisting he wear a formal suit. But on the premiere night of Mother India (1957), Dutt, accompanied by Geeta, turned up in an all-white, crisp kurta-pyjama with full-rimmed black framed glasses, recalled Devi. “He wore golden-coloured Pathani designer shoes, and spent most of his money on readymade garments,” he said. “His favourite dressmaker was Charagh Din at Colaba in then Bombay, but he had a Parsi female dressmaker at Mohammed Ali Road who knew his taste in clothes better than anyone else.”

After he tasted success, Dutt made numerous expensive purchases—a bungalow in Pali Hill, Bandra, a two-seater MG open-roof car in red that he drove himself, and a convertible DeSoto. He also spent a lot in building his own studio, with the largest shooting space at the time and only the second air-conditioned studio then after Mehboob Studios. He also bought an air-conditioned recording van in his mother Vasanthi’s name. It was called Sight and Sound and saw dubbing bookings from all well-known actors. Like other famous actors of his time, Dutt, too, had a farmhouse in Lonavala. He also spent a lot on cigarettes, said Devi, and bought imported whiskey from Surat and Daman and Diu.

But before success and splurges came trials and humble beginnings.

“We are the Padukones”

Dutt came into this world as Vasant Kumar, the eldest of five children. His original name meant spring, but he arrived much later, on July 9, 1925. His parents, Vasanthi and Shivshankar Padukone, were Saraswat Brahmins.

Vasant became Guru a few years after his birth as he kept falling sick and a faith healer suggested a name change as its remedy. Dutt was added later, after Lord Dattatreya.

“We are the Padukones,” said Devi. “When he started out in films, Guru Dutt ji would use Padukone Guru Dutt. But then industry people asked him to place Padukone at the end. So he started using Guru Dutt P. But it was only when he was assisting Gyan Mukherjee (his mentor) that Guru got completely rid of the P. Mukherjee told him, ‘It does not go with the Bengali in you.’ So it was Gyanji’s intuition that also became Guru’s lucky charm.” Why did Devi choose Dutt over Padukone? “Because I wanted to bask in the glory of being Guru Dutt’s bother,” he said, sheepishly.

Today, of course, Padukone is an equally famous surname, thanks to badminton player Prakash Padukone and his actor daughter Deepika. “Prakash Padukone is a distant relative from our father’s side. Deepika featured in my ads before she became an actor,” said Devi, who started making ad films and documentaries with cousin Shyam Benegal, the doyen of parallel Indian cinema (Benegal’s paternal grandmother and Dutt’s maternal grandmother are sisters).

Padukones are named so after their ancestral village with the same name; Dutt though was born in then Bangalore. THE WEEK visited the quaint hamlet in coastal Karnataka where his father hailed from. Shivshankar Padukone was initially a school headmaster at Panambur near then Mangalore, before moving his family of seven, including four sons (Dutt, director Atmaram, Devi and Vijay) and a daughter (painter Lalitha Lajmi, the third child), to Bangalore where he took up a bank job. (Atmaram did not use a surname, whereas Vijay, who was into advertising, was the only one to retain the Padukone surname).

“We can trace the achievements of the Padukones to more than a century earlier when one of the first Kannada writers Padukone Ramananda Rao became nationally known, and then to Guru Dutt Padukone to Prakash Padukone and now his daughter Deepika Padukone,” said journalist Subramanya Padukone. How does he feel sharing a famous surname? He shrugged his shoulder and smiled, saying, “We share our surname with our village, not the people.”

Time is in no hurry here nor are its residents, who all know each other. “The village hasn’t changed much even with all the fame and accolades; everything is almost as it used to be, at least as long as I have been around,” said Devarrya, 52, principal of a 100-year-old school. “Guru Dutt’s brother and his wife had once come to the village some years ago, but nothing of the family remains now.” The village somehow remains untouched by the glitter and glamour of Bollywood. Said Vishwas Padukone, 20, a doctor in the making: “We are aware of the prominent Padukones, but I believe in giving back to my village rather than simply disappearing into the blinding lights of stardom.”

“Would not cry out... he soaked it all in”

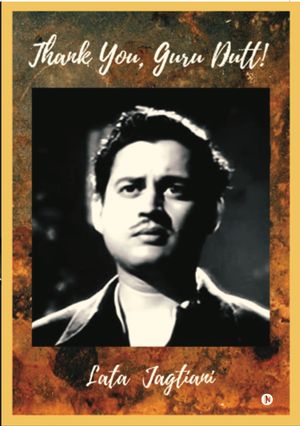

While the impact the village had on Dutt and vice versa is debatable, there is no denying that the Dutt we know of today was heavily influenced by his growing up years—he was a product of what he observed then, wrote Lata Jagtiani in Thank you, Guru Dutt!, her biography of the genius filmmaker she refers to as the ‘Satyajit Ray of Hindi cinema’.

“His parents were constantly fighting and that was a very sad thing for him to witness,” noted Jagtiani in her book. “In fact, his mother tried to educate herself, and finally when she cleared class 10 and received a pen as a prize that she got home, his father got so angry that he threw the pen away. Constant arguments between the couple led to a traumatised young Guru. His father was a very unstable person who was constantly changing jobs, and the family kept shifting base in the hope of doing well.” When Devi was asked about his father’s influence over the five siblings, he snapped, saying, “Totally nil—father was least bothered about us.”

Another instance that could have left a lasting impact on Dutt’s impressionable mind happened while the family was in Ahmedabad, where one of his uncles used to stay. “Somebody in the family at the time was mentally unsound and would often be violently thrashed for making noise. A young Guru, about five or six, witnessed it all. He saw a lot,” wrote Jagtiani.

Vasanthi, a multilinguist and prolific writer, wrote about her “very stubborn, impulsive son who always had a book in his hands” in an autobiographical essay published in 1979 in the now defunct Indian magazine Imprint. She said that her eldest “would not cry out, he would cry in, as he soaked it all in”. The older Dutt expressed his festering angst in the characters he built—emotive, expressive, nuanced, it was all personal to him.

“Quite the Bengali in his sensibilities”

But it was during his time with the Benegals in Calcutta, where the Padukone family moved for a while, that Dutt was further shaped into the master storyteller we know of today. He not only “beautifully adapted a Bengali way of life” but also got initiated into the world of cinema under the guidance of B.B. Benegal, youngest brother of Shyam’s father, and a renowned publicity poster artist. “He would often spend months at our place, right from his early teens to his 20s and beyond, because our families were very close,” said Asha Gangoli, daughter of B.B. Benegal. Gangoli’s mother, who was Dutt’s paternal aunt, used to be very close to him. “The moment he would come home, they would chat for hours late into the night. She was his forever go-to problem solver,” said Gangoli, who now lives in Pune. It was also at the Benegals that Dutt, who was brought up in a strictly vegetarian household, first tasted fish. He, of course, then introduced his siblings to it. “Dutt was quite the Bengali in his sensibilities; he was fluent in the language and preferred authentic Bengali cuisine any given day, notwithstanding his Mangalorean Saraswat Brahmin genes,” said Gangoli.

Recalling an anecdote from when Dutt was married to Geeta, Gangoli talked about the couple’s “deep fondness for fishing”. Once, the couple along with the Benegals went fishing at Powai lake and while looking for Rohu, Dutt became “very sombre and would not let anyone talk at all. There had to be complete silence”. “After they caught it, Geeta, being the typical Bengali, would hold that fish like a pro and cook it herself; he thoroughly relished her cooking,” said Gangoli.

Dutt would visit the Benegals at their Dharamtala market street home, and spend the night there even after he became an established actor. Gangoli recounts an instance when her father lost his cool over what he saw as Dutt’s Bambaiya attitude. “Dutt was used to his morning tea in bed. Coincidentally, my father arrived in his bedroom early in the morning that day. He saw this young man sitting on the bed, his hair tousled and teeth unbrushed, sipping a hot cup of tea, and went red in the face,” recalled the 82-year-old Gangoli, who is 18 years younger to Dutt. Mind you, this was when his directorial debut Baazi (1951) had become a hit and he had risen to instant stardom. “But my father did not change his attitude towards Dutt irrespective of the stardom he had achieved. He treated him like a brat,” she said.

But it was B.B. Benegal who referred Dutt to Uday Shankar’s School of Dancing and Choreography in Almora, now in Uttarakhand, in 1943. “Dutt was easily the most handsome young man there. All eyes were on him. He was so unassuming, shy and nervous. I remember he always had his camera around his neck. I wasn’t surprised when he discontinued dance—he had a feel for film direction. You can see the influence of dance in his movies—the photographic pattern of movements,” said Satyavati Gopalan, a Kathakali dancer on whom Dutt applied makeup before a performance at the academy, as quoted in The Legacy of Guru Dutt: 2025 Diary by Nasreen Munni Kabir that commemorates Dutt’s birth centenary year. The academy’s student progress chart, noted Kabir, mentioned Guru Dutt Padukone as a student who aced in every section, except games.

A year before Dutt left for Almora from Calcutta, the rest of his family moved to Bombay. His father found work as an accountant there. “Our father earned Rs750 per month and Guru would earn Rs1,750 as dance master in Uday Shankar’s troupe, where he had earned much praise on essaying the role of Laxman; Uday sir played Ram and his wife played Sita. He would send money from there to support my education,” Devi told THE WEEK from his home in Bandra’s Pali Hill. “He sent me to a boarding military school as he was very keen that I join the defence forces. Unfortunately, I failed the exam twice and that really hurt him badly. He stopped my education then and there.”

Soon, Dutt, too, joined his family in Bombay. A reason “he didn’t last long in Almora was, of course, the food. How could a Kannadiga, brought up on Bengali food, take to the pahadi khaana so easily,” quipped Gangoli.

“Warm and welcoming household”

In Bombay, the Padukones lived in a modest two-room flat in Vimal Villa, a two-storey building in the leafy neighbourhood of Matunga. In a corner right outside their ground floor flat lived a family of sweepers. Dutt would regularly chat with them, unmindful of caste, class differences, Vasanthi reportedly noted in a letter published in Kabir’s book. The family of sweepers continues to stay there even today, right next to the Padukone flat, which bears Vasanthi’s name. The flat remains locked, its open verandah being used as a storage space by others. But the memory of the Padukones still lingers here. Suranjan Karotiya, 60, remembers being told that his father was tutored by “Vasanthi ma’am at their home every day”. She used to teach in a school but also taught underprivileged kids at home. “Theirs was a warm and welcoming household,” he said. “We were sweepers, but they never made us sit separately. We even drank water in the same steel glass that they used for themselves.” He recalled how Vasanthi told him off for getting engaged at 16. “First, study well, earn for yourself and then get married,” she told him. She gave him money to buy books and school supplies. “It is because of her that I know to read and write the little English I know today. It is also because of her that I married at 26 and not in my teens,” said Karotiya.

THE WEEK visited the flat one weekend afternoon in March, along with Dutt’s only daughter-in-law Kavita, wife of his younger son Arun, and their daughter Gouri, one of Dutt’s two grandchildren. “Isn’t it amazing that all of them came down to live here in a 250sqft flat from Calcutta when the Quit India movement of 1942 was in full swing!” said Kavita, whose two daughters—Gouri and Karuna—are both assistant directors in Bollywood.

The small flat stands testimony to the tough times the family underwent since its move from Calcutta. Devi recalled an anecdote from their time at the flat: “Our neighbours, the Desai family, owned a Murphy Radio and they would play it out loud. I remember the sombre announcement of Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination at Birla House on January 30 at 5pm. We children were busy playing hide and seek in the building compound. I saw my mother rushing to the Desai home to listen to the news on the radio, but Mr Desai stopped her from entering the house. I don’t know why. My mother was a Gandhian; she worshipped him. In a state of shock, she remained standing outside their door to hear the updates. My father tried a lot to take her home, but she refused. When Guru saw her standing after he came home, he immediately went to a radio shop and purchased a second-hand Marconi radio.”

This, when Dutt was yet to find work on his return from Almora. He was in his 20s then. It was also around this time that he fell in love with his wife, then known as Geeta Roy. She lived in the same neighbourhood, in the famed Hindu Colony.

“Guru would send love letters to her through our sister Lalitha,” recalled Devi. “It blossomed into a sweet romance and it all happened during his time of struggle between 1944 to 1951 when he had enough time to play gully cricket and devour his favourite maska pav at Koolar’s, (a famous Iranian cafe) Kings Circle. Who knew she would also become his lucky charm. In a way, the two grew professionally together in the initial years.”

“Perfect combination of Dev’s talent and Guru’s genius”

When Dutt was desperately looking for work after his Almora stint, B.B. Benegal referred him to director V. Shantaram’s Prabhat Studios in Pune. Prabhat turned out to be the dawn of a new chapter not just in Dutt’s life but also Indian cinema. This is where his path crossed with actor Dev Anand’s, who became a close friend and collaborator. Their first meeting was serendipitous of sorts. They were both working on Hum Ek Hain (1946), Anand’s debut film. One evening, Anand had plans to meet the woman he was seeing at the time; it was her birthday and he wanted to wear his “best shirt”. Only, it was missing from his pile of freshly laundered clothes. After much convincing from his sister, he reluctantly wore another shirt and stepped out. As he was walking down the studio, he saw Dutt walking from the other end. Dutt recognised him, and introduced himself, saying he was working with the cinematography department and also handling choreography. “But Dev kept staring at Guru’s shirt. That is when the two realised that the dhobi had unknowingly interchanged their shirts and the two started laughing. That became the beginning of a great friendship,” Jagtiani told THE WEEK.

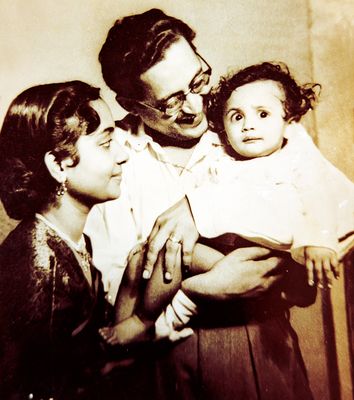

Anand gave Dutt his directorial break with Baazi; Anand produced it under his Navketan Films banner and played the lead. “Everything simply fell into place and worked like a charm in Baazi,” said Kalpana Iyer, a Bollywood buff and founder of Muzically, an online jukebox for Hindi film music. “He had the best team with the effervescent Geeta Bali, legendary S.D. Burman and lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi and, of course, ace cinematographer V.K. Murthy, who became his right hand for the next 13 years of his career.” Also, Geeta Roy, with whom he later had two sons (Tarun and Arun) and a daughter (Nina), was in top form and their romance was at its peak; Geeta Roy and Geeta Bali were best friends and it was Bali who made all the arrangements to get Dutt and Geeta married under the Hindu Marriage Act. ‘Tadbeer Se Bigdi Hui Taqdeer’ that Geeta sung remains a cult even today. Baazi marked a defining moment in Dutt’s career, which took off and how!

“It was the perfect combination of Dev’s talent and Guru’s genius that gave the industry some of its best and most successful films, beginning with Baazi, which was a super-hit. Both, deeply influenced by world cinema, brought the noir tradition to the Hindi film industry and, along with their breakthrough work, both also became famous for their string of affairs,” wrote Jagtiani in her book. In a public meet held in Karnataka soon after Dutt’s death, Vasanthi said that she was indebted to Anand, for he had stopped her son from committing suicide very early on in his career.

“Shoot in Guru Dutt style”

Baazi was just the beginning. Dutt, through his most profound works in his 13-year-long career as director, actor and producer, has etched his name as a pioneering filmmaker in world cinema. Many filmmakers of today like Hansal Mehta see him as someone way ahead of his time, a visionary always pushing the envelope. Mehta has, time and again, mentioned Pyaasa (1957) as a cinematic treasure, with its poetic storytelling and social commentary.

Those close to Dutt note that his mad passion and dedication to cinema both became his reason for living and later death, too. There was not a single aspect of his film in which he was not involved. “If Murthy was doing something, Guru had to go to the viewfinder first and see it. In one scene in Mr. & Mrs. 55 (1955), he kept at it. Finally, the whole day went by and only the next morning did he accept the take,” said Iyer. Jagtiani adds that “he has probably got the record for maximum retakes”. Then there was the time he was working on both Pyaasa and C.I.D. (1956)—while he had handed over the reins of C.I.D. to filmmaker and good friend Raj Khosla, he still directed all the songs of the film. He did this for almost all his films, given that songs were the closest to his heart, being a trained Kathak dancer and choreographer.

Dutt, no doubt, had a distinct style of shooting. In the 1950s, when most directors in the Hindi film industry swore by mid shots and long shots, Murthy told Kabir in an interview that Dutt was the first person to use the establishing shot (wide shot, often at the beginning of a scene that establishes the time, location and context). He would follow it up with close-ups that enhanced the expression and gave a unique cinematic quality to the performance. He was also the first to use the long focal length lens, the 75mm and 100mm. In 75mm, the face looks roundish, while the 50mm lens is the way the eye sees things. The use of these lens became known as the ‘Guru Dutt style’. Years later when Murthy worked for others, they would say, “Shoot in Guru Dutt style.” Take, for instance, the song ‘Sun Sun Sun Sun Zaalima’ from Aar Paar—he reportedly had the camera whirling around a car in a garage. For ‘Yeh Lo Main Haari Piya’, he shot it completely in back projection.

But what are songs without music? Adding that melody magic to the Dutt-Anand combination was O.P. Nayyar. Jagtiani, in her book, wrote about the “wild, wild trio”. “All three of them were quite wild; a combination of two geniuses—Nayyar and Dutt—along with a talent house that was Dev,” she wrote.

When Dutt was considering starting his own production house—Guru Dutt Films—and was looking for a composer, Geeta suggested Nayyar’s name as she had already sung for him in Aasmaan (1952). That is how Nayyar and Dutt came together for Baaz (1953). However, Baaz failed to create a buzz, just like Aasmaan and Chham Chhama Chham (1952), Nayyar’s second film as composer. He decided to leave for his hometown in Punjab, and asked Dutt, who had then just got married to Geeta, to pay his dues. Dutt told him that he was in no position to do so, but promised to give him work in his next film. That film was Aar Paar (1954), which went on to become a blockbuster with chart-toppers like ‘Sun Sun Sun Sun Zalima’, ‘Kabhi Aar Kabhi Paar’ and ‘Babuji Dheere Chalna’. Their collaboration continued with Mr. & Mrs. 55 and C.I.D.

It is interesting how Dutt got Aar Paar. After Baaz’s failure, Dutt was under a lot of stress. That is when actor-director Jagdish Sethi met Dutt and told him, “Actor Shyama praises you a lot, and would like to make a movie on bank robbery.” Dutt smiled and said, “If I like the subject, I am available for you, provided it has love in it.” That is how he produced, directed and acted in Aar Paar.

Many in the Indian film industry owe their career to him, like Murthy, Nayyar, Khosla, writer-director Abrar Alvi and actors Mala Sinha, Waheeda Rehman and Johnny Walker—they became his dream team. And, he did not just help them professionally but also financially. When Sinha’s house was raided by the income tax department and she had nothing left, it was Dutt who visited her the next morning, “with both his pockets full of cash, reassuring her of his help anytime”. “He would give away money left, right and centre,” said Jagtiani.

“Pyaasa was the result of his madness”

Following the success of Aar Paar and Mr. & Mrs. 55, Dutt had been on an all-time career high. And then he started work on Pyaasa, which was vastly different from the previous two films that had both romance and comedy. Dutt wrote Pyaasa in 1948-49 when he was unemployed. “It was that depressed, melancholic Guru, who when he used to write short shorties for the Illustrated Weekly in his free time, taking after his mother, wrote Kashmakash—a short story that was reflective of the dark phase he was going through in his own life,” said Jagtiani. That Kashmakash later went on to become Pyaasa, much to the chagrin of Murthy and Alvi, who told him not to take a chance with a film like that at a time when people were loving his happy-go-lucky narratives. Yet, Dutt went ahead with Pyaasa, opting for S.D. Burman, instead of Nayyar, for a sombre and more introspective music. It was also during the making of Pyaasa that he made his first-ever “serious suicide attempt”.

But Pyaasa paled in comparison to Mother India—larger in scope and scale—that released the same year. “Pyaasa was the result of his madness,” said Jagtiani. “He was in love with his art and everyone else was secondary, including his relationship and affairs. He would spend nights in the studio without even informing his wife; he was possessed.” That is the price one pays for marrying a genius, say those who knew the couple.

“He was an absolute insomniac; he could not sleep because his mind was racing all the time,” said Devi, who had joined his brother during the making of Pyaasa. He recalled his days with Dutt being hectic. On days he was shooting, Dutt would wake up early and have tea with milk after bath. “He would be in a loose gown and would sit with us for breakfast,” he said. “He would read the newspaper at the table.” After breakfast, he would get ready to go to the studio for shooting. “We usually left home at 8am,” recalled Devi. On days of no shooting, he would wake up late. Every Sunday, the first thing he would have in the morning was hot milk with malai and jalebi. “He was a splendid cook,” said Devi. “He would make fantastic masala omelette, tandoori chicken and biryani every Saturday and Sunday. He would have three cooks to help him.”

Gangoli, who once accompanied Dutt to one of his sets, described him as being extremely impatient on the sets. “He could not tolerate slow movers, one had to match his pace to work with him,” she said. Comedian Walker said he wanted his actors to put their life into the character and make it their own. “And if things went wrong, he would correct us and say, ‘Johnny, this is your dialogue. You can make it better if you want to, otherwise just follow the script,’” Walker is quoted as saying about Dutt, who would approve an improvised shot only if the former’s ad-lib dialogues elicited any laughter from the light boys and assistants.

“If he is the sun, I am the moon....”

Dutt had a funny bone, too, and played pranks on people close to him. Alvi once was discussing a script with Dutt when a burqa-clad woman came to see Alvi. He went into the living room to meet her. She told him how enamoured she was with his dialogue writing and asked him to write a role for her and give her a break in films. Alvi, surprised and confused, wasn’t sure if he could help. The woman insisted, and so he asked her to lift her veil, adding that unless he saw her face he wouldn’t be able to write for her. The lady refused. “After several minutes, just as Alvi got up to lift her veil, she broke into a loud laughter, with the entire crew standing behind going hysterical. It was then that Dutt introduced Alvi to his muse, actor Waheeda Rehman,” said Sathya Saran, whose Ten Years with Guru Dutt is a gripping read on the Dutt-Alvi partnership that gave us some of the most successful films of the time, including Aar Paar, Pyaasa, Kaagaz Ke Phool and Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962). Saran recalled that such was their chemistry that Alvi once said, “I am reflected light; if he is the sun, I am the moon and I shone.”

Saran narrated the time when Dutt gave Alvi his first stint as a dialogue writer. Dutt had Alvi locked up in a room and instructed his team to “give him all he wants—food, water, even a nautch girl, if he asks for one. But he has to write dialogues, so don’t let him out”. At the end of the day, Dutt would return, give his perfunctory nod without actually reading the dialogues, and ask him to return the next day. This continued for seven days. On the last day, after meeting Rajendra Singh Bedi (a famous dialogue writer), he came and told Alvi, “For someone like me who is new in the world of direction, he might make me direct the film according to his script. And so, I don’t want him to write; you write my next film.” That is how Aar Paar came to be, kicking off a partnership that lasted till his last breath. “Guru Dutt worked with his heart, Abrar with his brain,” said Saran. “There was a lot of logic in what Abrar did and a lot of emotions and feelings in what Dutt did. They were both a good foil for one another.”

With Alvi, who directed Dutt in Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, he also had that rare freedom to voice his difference in opinion. “My brother never interacted with other directors,” said Devi. “But with Alvi, he would argue.” He cited the example of Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, where its financier and distributor felt the need for a Gujarati song. “When I went to their office for instalment, Kapurchand ji said to me, ‘The film is serious; there should be a Gujarati song, where she [Meena Kumari] is getting ready for her husband,’” recalled Devi. “Abrar saheb was furious; but Dutt ji said to him, ‘Abrar, sorry, but can I picturise this song without touching any of your dialogues or scenes?’ Alvi was surprised, but he allowed Dutt ji to picturise it on Meena Kumari. Later, even she liked the picturisation. This was the song ‘Piya Aiso Jiya Mein’.”

While he was keenly into filmmaking, Dutt did not always want to act in all of his films. He would look for other actors to play the lead—Shammi Kapoor for Aar Paar, Sunil Dutt for Mr. & Mrs. 55, Shashi Kapoor for Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, but lack of availability of dates from these actors left him with no choice. “What a nuisance! I keep wanting to escape being cast, but it always comes down to me again,” he once told Waheeda, who recounted this to Kabir in an interview in 1988.

It was the same with Pyaasa. Dutt wanted Dilip Kumar as the lead. “Dutt met Dilip Kumar and his brother Nasir Khan in [director and producer] B.R. Chopra’s office. We, too, had our Guru Dutt Films in the same compound at Kardar Studios, Parel,” recalled Devi. “It was agreed by both brothers (Dilip and Nasir) that Dilip saheb would do the muhurat shot. Our mother and Geeta bhabhi (sister-in-law) were waiting with the pujari (priest) to start the shoot (mother to press the camera switch and Geeta to clap the board in front of the camera). The muhurat time was fixed for 11.30am, but Dilip Kumar saheb made us wait for long. Finally, he did not show up, and our mother yelled at Dutt in Konkani, ‘We have waited long enough for him; cancel him and you be the hero.’ He agreed but there was no time to do the makeup. So he told Murthy to instead shoot without a human face. That was how a shot showing a foot crushing a dead bhawra (bee) was taken.”

“A league apart”

Pyaasa was a sleeper hit, and buoyed by that, Dutt made Kaagaz Ke Phool, the first Indian film to be made in CinemaScope. But it bombed at the box-office, so much so that Dutt had to mortgage his production studio, his Pali Hill bungalow and Lonavala farmhouse. Dutt never went back to making films. He did continue acting, giving a smash hit like Chaudhvin Ka Chand (1960), his most successful film financially. Devi said he kind of redeemed himself with Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam. His last appearance was in 1964 in Baharen Phir Bhi Aayegi, but he died before the climax could be shot. The film was later re-shot with Dharmendra in the lead and released in 1966.

There have been various theories about his sudden death, but Devi blamed Dutt’s ignorance for it. “He simply did not know that the combination of sleeping pills and alcohol could prove lethal. That is all there is to it,” he said.

Those close to Dutt said that trauma, loneliness, sadness and depression were his constant companions. Even the love letters he wrote Geeta during their courtship days carried a hint of melancholia. THE WEEK accessed one such letter from the Arun Dutt collection, written in 1953 before their marriage. Though it has a very romantic tone, he also writes about his sense of loneliness and isolation.

“He was shy and a recluse as a person and the world knows that by now,” said Gangoli. “Had he been around, I do not think he would have ever stood outside his house on his birthday, waving out to fans.” But he did speak to a select few, and asked for help. One of them was the late Dr Jaygopal Benegal. “As you know, Dutt went through various episodes of attempted suicide, and a couple of times he called my brother for help,” said Gangoli. “I remember my brother saying that when he went to Dutt’s place on those occasions, he had found him in a pretty bad shape and helped him to the hospital.”

Dutt’s films were a slice of his own life. In Pyaasa and Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, he holds a mirror to an immoral society, but it also comes across as a purging of himself. Likewise, in Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, Rehman’s (the male actor) role was modelled on Dutt. It is said that Geeta had refrained him from making the film, saying it was like showing their life on screen. But he would not listen. Both husband and wife took to the bottle, distant and hardly communicative after a point.

Following his death, the Dutt family suffered a number of early losses. Geeta died at 41, eight years after him. Their eldest son Tarun, too, took refuge in alcohol and died at 34. Arun died at 58 in 2014. Arun married Kavita, a Muslim. “It is a shame that I never got to meet Dutt as he died young, at 39,” said Kavita. “Of course I knew Arun was from the Dutt family, but there was never a halo around them; they were very grounded. Arun was more like his father—very much to himself, but Tarun was outgoing, an extrovert whom everyone knew.” Gouri remembers her father Arun spending a lot of time with family. “One reason, I think, is that he did not receive it in sufficient amount from his father. That is why he ensured his own children always had him around,” she said. Nina, Dutt’s only surviving child, is a singer, and is married to production designer Naushad Memon and has two children.

Also Read

- 'Dhurandhar' box office collection day 19: Ranveer Singh starrer beats 'Kantara: Chapter 1' becomes highest-grossing Indian film of 2025

- 'Dhurandhar' box office collection day 18: Ranveer Singh starrer beats Vicky Kaushal's 'Chhaava'; becomes the biggest Bollywood grosser of 2025

- 'Dhurandhar' box office collection day 17: Ranveer Singh starrer to beat 'Baahubali 2' and 'Pathaan' today; gears up to hit Rs 800 crore globally

- Actress Nora Fatehi’s car hit by drunk driver in Mumbai’s Amboli

- 'Dhurandhar' row: Ex-Pakistani minister Nabil Gabol says he doesn't have enough money to call for international ban

- 'Dhurandhar' box office collection day 16: Explosive third Saturday on the cards for Ranveer Singh starrer

The rest of the family is not “too connected” with the film industry, said Gangoli. Dutt’s brother Vijay had little to do with Bollywood; his twin sons are in advertising. “Atmaram, on whom the mantle of Guru Dutt Films unfortunately fell (after Dutt’s death), was a documentary filmmaker. He managed it with great difficulty, and didn’t get too much success. His wife (Nagaratna, a dancer and singer) stayed away from the limelight completely and she kept her daughter away from it as well,” said Gangoli.

Yet, the question remains: What does Dutt mean to the Gen Z of today? Would they have the patience to sit through a black-and-white, slow-paced, languorous and reflective Pyaasa? “No, they won’t.” Kabir told THE WEEK. “But it does not matter.” Cinema has that peculiar quality to it where it transcends time and space and remains available to the connoisseur who wishes to devour it, even decades later. Dutt remains a legend to be celebrated because his biggest contribution was his originality and fearless love for cinema—chasing art rather than box-office numbers. “This alone sets Dutt a league apart and he will continue to dominate that league in the next 100 years because it is not easy to be a Guru Dutt. They don’t make them like him anymore.”