The jungle fox is back in Assam. Drishti Rajkhowa alias Manoj Rabha is inseparable from the land of his birth, like the Brahmaputra that meanders thousands of kilometres through China (Tibet), India and Bangladesh. And like the mighty river, the once elusive deputy commander-in-chief of the insurgent outfit United Liberation Front of Asom (Independent) has had a profound effect on the lives of people in the northeast, especially Assam. The state has seen decades of violent secessionism that continues to impact the geopolitics of China, India and Bangladesh, with far-reaching consequences for the entire subcontinent.

Drishti, 52, has become a link between the past and the future. After living underground for 30 years, he is now waking up to sunrises on the sacred river. He has started to don modern caps instead of his trademark Assamese headgear. But, he always wears some headwear; it is useful to divert attention from his sharp eyes. He also wears a mischievous smile that occasionally turns into tepid laughter, before being quickly absorbed by his controlled exterior. He has the gait of a seasoned hunter; you can easily imagine him being at home in the dark, distant mountains and wading through swift waters in the deep jungles of Assam.

But, today, burly men in black safari suits surround him. Drishti surrendered to Indian forces in 2020, making him the biggest catch in recent times. Since then, he has shuttled between a safe house in Guwahati and a rehabilitation camp in Goalpara, around 130km west of Guwahati. As second-in-command of ULFA(I), Drishti had been running some of the outfit’s biggest operations and he has been questioned by multiple Central agencies. His surrender raises hope of an end to the ULFA-led insurgency that has plagued Assam and the northeast since 1979.

ULFA was started by a group of five young men―Arabinda Rajkhowa alias Rajib Rajknowar, Pradip Gogoi, Anup Chetia, Bhadreswar Gohain and Paresh Baruah―and their adviser, Bhimkanta Buragohain. The undivided ULFA was led by Arabinda. After the split, Paresh took over ULFA(I). ULFA advocated a “sovereign, socialist Assam’’ and received mass support, drawing cadre from all sections of society. But, over time, it turned into a gun-running, divisive, casteist and extortionist outfit, aided by inimical foreign forces. It became willing to kill and plunder, thus alienating the masses.

When THE WEEK met Drishti, his fatigues camouflaged him till he was close enough for his bespectacled face to be visible in the night. He greeted me with a smile and apologised for running late. He led us to a bonfire by the Chandubi lake, which lies at the foot of mountains in Assam’s Kamrup district. “This used to be our hideout for launching attacks on security forces in other districts,” he said. “I have come here after a long time.’’ The place is a tourist attraction today and this is his first visit without weapons to protect him against men and beasts (mostly elephants). But, even without AK-47s or RPGs―which were among his favourite toys―his skills are formidable. Drishti was an IED expert and the biggest weapons supplier for ULFA.

He led ULFA(I)’s 109 battalion which mined a CRPF convoy in 2010, killing five and injuring 33; this was just one among the many attacks against Indian forces that he carried out or planned. He was instrumental in making ULFA capable of ambushing the Indian Army in Manipur’s Chandel district in 2015. The operation that killed 18 soldiers was a combined operation with other insurgent groups of the northeast. India had responded with a cross-border strike in Myanmar.

From the banks of the lake, Drishti led us to a quiet spot on a hill, flashing a torch to help us follow on a pathway strewn with broken tree trunks. It seemed that no one had visited the spot of late, except the family which had painstakingly prepared a meal for us. He was pensive as we settled down, but little joys like freedom and fresh air seemed to draw out the man who had once gone seven days without food while hiding in no man’s land between India and Bangladesh. He graciously welcomed a conversation.

“This seems like a second life to me,” he said, as he devoured mashed potato, eggplant and rice. “I was stuck in no man’s land. My wife, a cancer patient, was in India and my children were in Dhaka with mummy (Paresh’s wife Bobby Bhuyan Baruah). It is a miracle we are together again.’’

His wife Lilla D Marak crossed over to India on February 2, 2020. He surrendered and returned on November 13, 2020, but their children Priyanka, 16, and Prateek, 12, were left behind in Dhaka with Bobby. The kids were covertly brought to the Indian border in an operation led by the Assam Police under close supervision of the Director General of Police Bhaskar Jyoti Mahanta and ADGP (special branch) Hiren Nath. The Border Security Force provided safe passage into Assam on September 4, 2021. The smooth inter-force cooperation aside, it was the rarest of operations―the Assam Police had reunited a top ULFA leader’s family, giving them hope of a new life, in the hope of building a new Assam.

Prateek is elated to be reunited with his parents. He has left behind a luxurious life with Bobby, who is also a trained ULFA member. She has adopted Anik, the nephew of ULFA’s slain publicity secretary Mthinga Duimari, and is raising him with her younger son, Akash. The boys have reportedly left Bangladesh to join her eldest son, Tahshim, in Malaysia. Prateek was born in Bangladesh and was raised a Muslim. It was quite the shock for him to realise that he was not Muslim. He is slowly reconciling with his new identity. He cannot speak Assamese well yet, but has taken a quick liking to Assam. “I want to be like my father, but I want to be an IPS officer,’’ he said, perhaps inspired by the policemen he sees around him. Prateek and Priyanka have friends in both Bangladesh and India. “I am not in touch with them, but my father says I can use Facebook or Instagram after I turn 18,’’ said Priyanka, who wants to be a lawyer.

Lilla, 39, had gone to Bangladesh when she was 18. “Women in ULFA undergo 45 days of training, while men’s training lasts three months,’’ she said. “I learned to use arms and underwent intense physical training. It makes you mentally and physically disciplined.’’ Both Drishti and Lilla lament the lack of discipline in the overground life. “Our lives revolve around waking up, making tiffins and dropping the kids for classes. Some laziness has crept in,’’ said Drishti, albeit contentedly.

The children are adjusting to their new lives well. When they miss aunt Bobby, they scroll through their parents’ mobile phones to find pictures of outings with her. Bobby was a pillar of support when the family most needed it. She has knee problems and is alone in Dhaka. It is learnt that she occasionally travels to Malaysia, but cannot join her husband, who is hiding in China’s Yunnan province.

“It is difficult for her,” said Lilla. “She has been away from her husband for so long and misses her extended family in Tinsukia (Assam). Her sons have been stopped at immigration and she gets frantic. She wants to return to India, but she cannot do that without his permission.’’ Paresh, 65, has dental problems, but his spirit remains that of a fighter. There are intelligence reports of him living with a Chinese woman, but the Rajkhowas deny it. “It is a ploy to discredit him,’’ said Drishti.

He attempted to join Paresh in China twice after Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina assured Prime Minister Narendra Modi that she would cut the supply chains of Indian insurgent groups (IIGs) on Bangladesh soil. “In 2015, I planned to travel via Myanmar, but the border was sealed because of the Rohingya crisis. The second time I tried was before my surrender, but I could not make it,” he said.

The People’s Liberation Army of China shares a symbiotic relationship with IIGs. It offers refuge and uses them in overt and covert operations against India. Without its help, ULFA, the National Socialist Council of Nagaland and many other IIGs would be mere irritants and not threats to Indian security forces.

Intelligence reports suggest that Drishti had visited Ruili in Yunnan to attend strategy meetings with top ULFA leaders in the presence of PLA officers, but Drishti denied it. There are reports of Paresh’s nephew going missing in China and his elder brother appealing to him to locate his son, dead or alive. Unconfirmed reports suggest that the boy was given the capital punishment on suspicion of being a traitor. The death sentence is quite common in ULFA(I) camps; cadres are summarily court-martialed on mere suspicion and executed by firing squads. As recently as in May 2022, ULFA(I) released a statement that cadres trying to surrender had been executed.

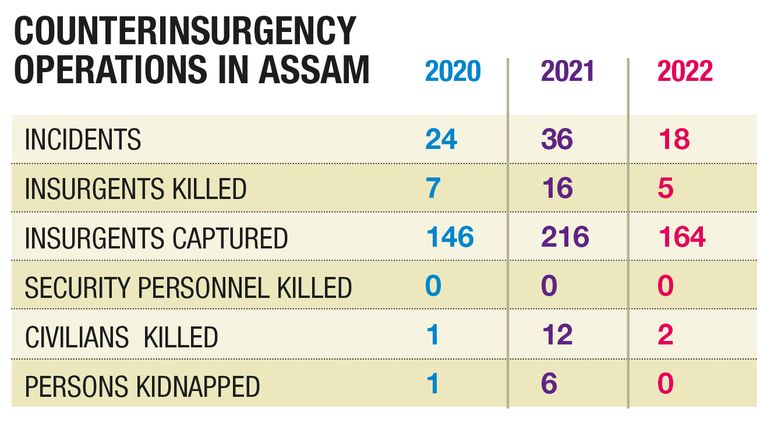

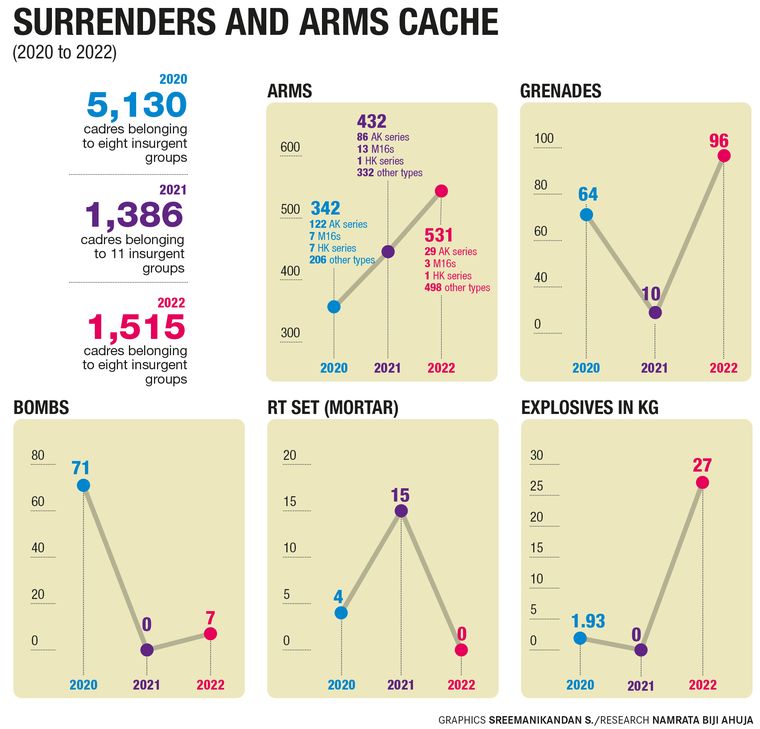

However, in the last two years, tactful statecraft by Indian forces, particularly the Indian Army and the Assam Police, has resulted in the largest surrenders ever of 8,031 militants, from different insurgent groups, with 1,305 highly sophisticated weapons.

Before his surrender, Drishti had last entered India in 2016 for a joint operation in Meghalaya with the banned Garo National Liberation Army (GNLA). But, after GNLA commander-in-chief Sohan D Shira was killed by Indian special forces in 2018, the pressure mounted on ULFA. “The collection (extortion) activity was hit badly and funds dried up,” said Drishti. “In Bangladesh, people refused food and shelter. We were being chased day and night. I finally surrendered.’’

Drishti’s gratitude is split between Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma, who gave him a fresh start, and Paresh, who gave him permission to surrender. At a time when security forces were closing in on him, Drishti got a lease of life thanks to the government’s surrender-cum-rehabilitation policy. He got a fixed deposit of 04 lakh and was trained in farming and horticulture. He now grows bananas and dragon fruit in Goalpara, with at least 200 surrendered ULFA militants. He also got two fisheries and piggeries as part of the rehabilitation scheme.

We met a dozen surrendered ULFA militants in Goalpara. They lead productive lives, worrying only about the next yield, providing for their families and educating their kids. Makhon Rabha, a sergeant major in ULFA, who operated from Bangladesh and returned to India in 2017, said he learned the true meaning of freedom after coming out of jail. “I was released after my case was closed and now I am working in an NGO,” he said. “I feel I am doing something good to sustain my livelihood.’’ But, he is anxious about the future of peace talks. “ULFA is still alive because of its history,” he said. “Government policies keep changing. Look at what happened to the Naga people? They are still living in uncertainty. If peace is the goal, the government should resolve the ULFA issue soon.’’

Pulin Hato, a sergeant major known by his alias Sandbrock Hato, joined ULFA in 1997. “Those days every villager was joining ULFA,’’ he said. “I trained in Bhutan and came to upper Assam for operations and extortion. But I had to leave ULFA in 2003 as my life was under threat.’’ Hato wants to contest the assembly elections and “work to develop the region”.

Rakesh Reddy, superintendent of police, Goalpara, said Drishti’s surrender encouraged other militants to do the same. “We are helping their rehabilitation, but also monitoring them,” he said. “The instinct to extort or influence people may still be there and can be stoked by temptations.”

ULFA has not reacted violently to the en masse surrenders this time. Like all militant outfits, it kills dissenters. This has been done relentlessly since 1999 when former cadre joined hands with intelligence agencies to form SULFA (surrendered ULFA), which helped in tracking and killing families of ULFA leaders across Assam. The horror of the secret killings still haunts Drishti. “Some people entered my house and killed my parents,” he said. “Our relatives, who lived next door, heard the shouts and screams but could not do anything.’’

D.K. Pathak, former director general, BSF, was Dibrugarh SP when the first ULFA surrenders happened in 1993. He said the indoctrination was heavy and that not all surrendered militants have returned to normal life. “Considering their crimes, I am not a big fan of surrender policies,” he said. But, Mahanta, the Assam DGP, said that the surrenders are a result of proactive actions. “You have to hunt,” he said. “But, we cannot and should not kill everyone. We focus on three outcomes―surrender, ceasefire, peace talks.”

Also read

- Pro-talk faction of ULFA formally disbanded; end of a 44-year struggle

- Historic day: ULFA signs peace deal with Centre, Assam govt

- Exclusive interview: ULFA top gun Drishti Rajkhowa speaks from his secret hideout

- How surrendered women militants in northeast are being rehabilitated

- 'ULFA threat is almost over': Assam DGP Bhaskar Jyoti Mahanta

- 'Paresh Baruah not averse to returning to India': ULFA pro-talks leader

As we visited Drishti’s childhood home in Goalpara―a plot of land where neither the house nor the farm has survived―he breathes heavy. “I could not come back, I was busy with operations,” he said. “At times, I feel that I lost my parents because of my actions. Those days, we thought we needed to fight for our people and Assamese identity, which is why I joined the organisation at a young age. But, so much has changed. The government is receptive and people are coexisting peacefully. Every revolution has an end. We just have to find it.’’

ULFA’s pro-talks faction is camped at Mangaldoi, about 70km east of Guwahati. The dusty, damaged road gets narrower as we get closer to the camp. The road is flanked by thatched houses, where the poorest families reside. As ULFA(PT) leader Pranjit Saikia disclosed that the houses were occupied mostly by Bangladeshi migrants, the tension was palpable―a reminder of ULFA’s hard stand against illegal immigrants.

Saikia was trained to use heavy weaponry in Pakistan, along with Drishti. The bullet marks on his arms and splinter injuries on his stomach speak about his violent actions to preserve Assamese identity. “They (Bangladeshi immigrants) take over our lands and stay illegally,’’ said Saikia. “Carpenters, drivers, everyone is Bangladeshi. As a result, the benefits of economic activity are going to them instead of the indigenous people. Whether the National Register of Citizens happens or not, we want this issue resolved soon.” However, ULFA(I), under Paresh, has recruited and trained Bangladeshi migrants, too. In fact, recent surrenders include such cadre. It seems like operational imperatives took precedence over ideology for the ULFA(I) leadership.

For ULFA(PT), apart from illegal migration, a major concern is rights over land and resources. “Industries are welcome, but the land should belong to Assamese and the benefits should go to people of Assam,’’ said Saikia. Sensing the issue of land rights can stir trouble afresh, the Assam government removed fencing around ULFA camps. So, the Mangaldoi camp’s fields run into the farms of ordinary Assamese folk. ULFA may dislike the change, but the “camp culture’’ is being stamped out, drawing lessons from Nagaland where the enclosed camps of the NSCN and its factions resulted in a parallel government.

Close cross-border ties of the people of the northeast―revolutionaries and common folk alike―with neighbouring countries is a reminder why strict counterinsurgency operations have not worked so far. A humane surrender policy is a welcome change for many.

Anup Chetia, a founder-member who is now leading talks for ULFA(PT), recently got his daughter married to a Bangladeshi boy settled in Australia. The couple were dating when Anup was in a Bangladeshi prison. “Love wins over all odds,” he said. “We had a reception in Tinsukia, which was attended by Paresh Baruah’s elder brother, Drishti and many other leaders.” Paresh gave his blessings over the phone. Anup said that as far as the peace deal is concerned, the ball was in the Centre’s court. “We have given our final proposal,” he said.

The pro-talks and independent factions of ULFA might have split, but the fact that Anup did everything he could to help Drishti’s wife return to India for treatment shows the continuing camaraderie.

Can Drishti’s return lead to Paresh’s return? The future hinges on Drishti and other surrendered militants and their control over instincts and temptation. A police officer recently told Drishti that he can stop using headwear as he is now a civilian. “I have given up all things that were part of the revolution, but I feel comfortable with a cap,” Drishti told me, recalling all the times his trademark headgear helped him weather storms while hiding in the same hills and forests that are embracing him now.