Arvind Kejriwal seldom wore a turban during his numerous visits to Punjab in the past several months. Against the backdrop of anger over the emotive sacrilege issue, the Delhi chief minister kicked off his party’s campaign in the state in June 2021 with a pledge to reduce electricity rates. It was a conscious effort to keep off hardcore Panthic issues and stick to the bread-and-butter matters of electricity, water and education that has held its government in Delhi in good stead.

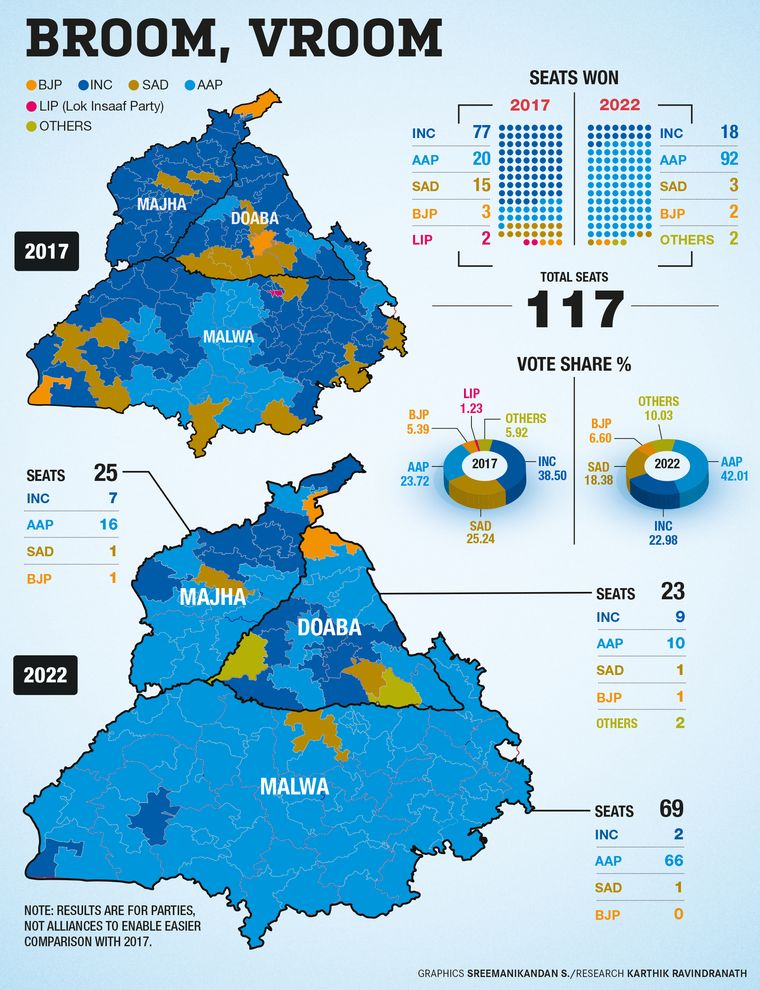

In 2017, the AAP tried hard to shake off the ‘outsider’ tag, but this time, that very fact became its USP; its track record in Delhi worked in its favour. If the word ‘change’ was the leitmotif this election, the AAP’s landslide victory, winning 92 of 117 seats, shows that the Punjabi voter has rejected the traditional parties, with stalwarts of the Congress like Navjot Singh Sidhu and Chief Minister Charanjit Singh Channi and the Akali Dal’s Sukhbir Singh Badal and former chief minister Captain Amarinder Singh falling by the wayside. Trust has been reposed in a non-Punjabi party, and there is whole-hearted acceptance of a non-Punjabi leader.

The farmers’ protest over the three farm laws that were eventually withdrawn formed the backdrop of the election and became a channel for the expression of discontentment among people, cutting across castes and social strata. The AAP capitalised on this mood by building a strategy around it, which was encapsulated well in the pithy slogan—‘Ik Mauka AAP Nu, Ik Mauka Kejriwal Nu [A chance for AAP, a chance for Kejriwal]’.

“Our slogan was a reflection of what the people wanted,” said AAP leader Manjit Sidhu. “And here, the youth were a big factor. Their restlessness with the present scheme of things turned the tide in our favour.”

Party leaders say the preparation for Punjab began right after the AAP’s massive victory in Delhi in 2020. Kejriwal appointed Delhi MLA Raghav Chadha, one of his closest confidantes, as co-in charge of the state.

While it emerged as the main opposition party in the 2017 assembly elections, the AAP had a series of electoral setbacks since then. It won just one seat in the state in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. It also fared poorly in the civic polls in February 2021. The state unit was in disarray, with local leaders rebelling against the Delhi Durbar, comprising Kejriwal and his confidantes.

As it got its house in order and a strategy moving, it was helped in a big way by the infighting in the Congress. The high court order in the sacrilege case became a tipping point for the discontentment against the Amarinder Singh regime. The farmers’ unrest only added to it. The protests helped the AAP, but it did nothing for the party borne out of the agitation—the Sanyukt Samaj Morcha.

The AAP has had to deal with organisational weaknesses and lack of recognisable local leaders, except for Mann. Eventually, it did get an organisational structure in place, and a senior leader or legislator was put in charge of each constituency. The AAP also made sure it did not repeat its past mistakes. Unlike in 2017, it named its chief ministerial candidate—Mann, a Jat Sikh from Malwa region, AAP’s stronghold, and a household name in the state. There was also the perception that the party was close to Khalistani elements, which had alienated not just the Hindus but also others wary of militancy rearing its ugly head again. This time, the party steered clear of ticklish regional and religious issues. Also, keen on not being seen as sympathetic to the separatist cause, it kept NRI support at bay.

The AAP was the first to announce its promises, starting with the free power pledge. Its other populist promises included Rs1,000 to women per month, free medical treatment and free education. The campaign focused on Kejriwal as the leader who brought about a change in Delhi and could do so in Punjab as well.

“The results prove that the people did not just vote for change but they wanted to teach the traditional parties a lesson. That is the reason why the Congress and the Akali Dal have been decimated,” said Ashutosh Kumar, chair, political science department, Panjab University.

It was the feedback from the ground that the AAP was getting traction that had forced the Congress to replace Amarinder Singh with Channi as chief minister. The choice was also guided by the assessment that the AAP was making inroads into its dalit vote bank.

With Punjab handing the AAP its first foothold outside Delhi, the state now holds immense significance for the national ambitions of Kejriwal and his party. The party will form its government in a full-fledged state, which, unlike Delhi, will give it control over police and state administration. After the BJP and the Congress, the AAP is now only the third party to be in power in more than one state.

Also read

- Assembly elections: BJP, AAP ride on delivered promises and effective communication

- Yogi decimates opposition, cruises to victory in Lucknow

- The divided caste vote in UP

- Rise of the beneficiary class

- 2022 Assembly elections: Is it sunset for the Gandhis?

- AAP poised to replace Congress and out-compete BJP: Prof Pramod Kumar

In the run-up to the next Lok Sabha elections, Kejriwal is bound to emerge as a possible contender to take on Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Also, the term of seven Rajya Sabha MPs from the state would end this year, and the party is set to get a stronger voice in Parliament. The victory also comes as a boost to the AAP as it would look to make inroads in poll-bound Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh.

It is widely accepted that Kejriwal will be the super chief minister. But his endeavour to make a difference here is not going to be easy. While Delhi is a small city-state and revenue surplus, Punjab, after having seen prosperous days, is now going downhill and is burdened by huge debt. Besides the issues of unemployment, drug addiction, cross-border terrorism, education and health, the party will have to deal with regional issues like the sacrilege matter, release of Sikh political prisoners and the question of water sharing with Haryana.

Mann and his legislators, meanwhile, will have to learn on the job as they have no administrative experience. “The party had decided to form a team of experts to overcome this challenge,” said political analyst Prof Harish Puri. “They do not know how bureaucracy or the police functions in the state.” The police and bureaucracy have been battle-hardened since the days of militancy, and have their own way of functioning.

Party leaders say the AAP has the political will to bring about a change, unlike the Congress and the Akali Dal. “The same kind of scepticism was expressed when the AAP came to power in Delhi,” said AAP leader Priti Sharma Menon. “But we have provided a model of governance in Delhi that is now being emulated in other parts of the country.”

However, it is not certain if the present mood of acceptance of Kejriwal and his team of Delhi-based leaders in the state unit will continue. Punjab is the AAP’s stepping stone into the national arena and could well turn into a stumbling block.

—With Pratul Sharma