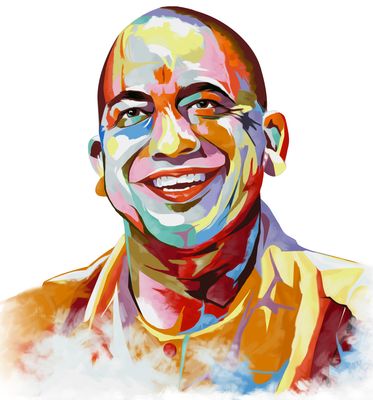

Of all the questions that physics and philosophy have dealt with the most confounding one is about the nature of the human gaze—never the same for different people. As for mundane everyday objects, so for governments, perceptions vary widely, coloured by experiences and beliefs. As the Uttar Pradesh government led by Yogi Adityanath completes four years in office, it is this challenge of the human gaze it grapples with.

This is a government strongly welded to the image of its leader—a man considered saviour and foe, in equal measure. The good his government has done lies buried beneath the unrelenting criticism of him being intolerant and heavy-handed. But does that cacophony drown out a fair assessment of the last four years? Is there a narrative beyond the obvious?

Let us start with the charge of an unrelenting crime graph. A look at the data from the National Crime Records Bureau shows that in 2017, UP accounted for 12 per cent of all crimes registered under the Indian Penal Code and Special and Local Laws. In 2019, the latest year for which this data is available, this share was 12.2 per cent. As for crimes against women, on just one of the most heinous parameters—rape—the crime rate (per lakh population) in 2017 was 4; in 2019 it was 2.8. There were 8,990 cases of rioting in 2017, of which 34 were communal and 14 sectarian; it came down to 5,714 cases in 2019, none of them communal or sectarian. But here is the catch—the report is a collection of figures that emanate from records provided by the governments of the respective state or Union territory.

Every noteworthy achievement of this government has come under the scanner—fairly or unfairly so. The 2019 Kumbh in Prayagraj, for instance, while lauded for its smooth management, was also blamed for pulling away money from other development projects, most significantly from the government’s commitment to pothole-free roads. Even today in Lucknow, the state’s capital, within its most high-end localities, stretches of roads are hidden somewhere amid yawning craters. Last-mile road connectivity remains challenged, even off the 302km-long Agra expressway built by the previous Samajwadi Party government.

The Samajwadi Party has repeatedly criticised the government for only carrying forth what it started. Party president Akhilesh Yadav speaks of two achievements most vociferously—the Agra expressway and the distribution of laptops to students. His party also lays claim to initiating a change in the state’s tourism policy and of launching talks for big-ticket investments like the one with furniture giant IKEA.

In governance, however, continuity is often an achievement.

Prashant Trivedi, associate professor (sociology) at the Giri Institute of Development Studies, Lucknow, said that the continued pursuance of development projects had changed the perception of the state. “There has been continuity in development projects such as the Metro Rail and the Purvanchal expressway. Governments have a tendency to discontinue the good work of their political opponents,” he said.

Madhukar Jetley, erstwhile adviser to the Samajwadi Party government on NRI affairs, said, “This government has not stopped lifeline projects of the state. It has taken the development agenda forward. There is no denying what it has achieved.”

Yogi Adityanath is an unrelenting taskmaster. One ongoing guessing game among his party men and the bureaucracy is: who between him and Prime Minister Narendra Modi is the earlier riser. He never lets the pressure ease. When the country was still figuring out how to tackle Covid-19, he would get into a huddle with his core team of advisers every morning. It was on one of those mornings that he received news of his father’s death. The meeting did not pause.

Under him, there is a great emphasis on targets. This can be somewhat of a mixed blessing.

The manager of a PSU bank in Lucknow said that the pressure of giving loans to entrepreneurs had meant that the District Industries Centre (the nodal body in a district for providing loans and training to entrepreneurs, and also monitoring credit flow) had passed on the task of verification of critical parameters to the banks. As examples, he cited cross-checking of the lease status of the premises on which an MSME (medium, small and micro enterprise) unit was to be operated or verifying whether the loan taken in the name of a woman was actually for the use of a male member of the family.

Similarly, the rapid development of industrial centres overlooks basic problems such as waste disposal and drainage. The state’s much-discussed ‘one district, one product’ scheme that capitalises on traditional skills was hampered earlier by an injudicious choice of products. Kanpur, for instance, once called the Manchester of the East for its textiles, had just leather as its product of choice.

Roli Misra, an associate professor at Lucknow University’s department of economics, said, “The scheme focuses on supply side, not on demand. Hence, despite being touted as a game-changer, it is not generating as much employment. The state has been unable to curb migration.” However, as industry officials point out, the scheme is “evolving”. “There is an increased pooling of thoughts and application of minds,” said an official.

On the brighter side, in the same sector, the dogged pursuance of targets has meant that while in 2016-17, the credit targets achieved for the sector were 112 per cent, in 2019-20, these stood at 137 per cent (after a peak of 149 per cent in 2017-18). Fresh MSMEs stood at 8.8 lakh and the amount disbursed to them was 031.5 lakh. It is this sector that has provided maximum employment, too.

Sanjay Kumar Singh, professor (business environment area), at the Indian Institute of Management, Lucknow, said, “Things are definitely moving in the right direction. Connectivity and energy have been two of the biggest bottlenecks in the state. The government is working towards these and producing results.”

Beyond these, there are initiatives that show a government committed to its people. Something as small as introducing khadi in the mix of polyester fabric for school uniforms so that government school children are more comfortable is not a thought usually attributed to state governments pushing agendas that focus on the vote-worthy.

The state has also benefited from what the prime minister refers to as the “double engine” of growth. A BJP-led government at the Centre means that clearances are swifter, say, for the setting up of airports for short-haul flights. Again, this is a mixed blessing as the shortcomings of the Centre rest heavily on the state, too.

Ramavati Nishad, who works as a house help, said, “The government gave us money during the lockdown. But then it took it all away as prices of all essential commodities went up. Running a kitchen is very difficult.”

It is also the Centre’s stance of curbing the democratic spaces of protest that gets conjoined and magnified in the state.

Sunil Singh, a long-time associate turned rival of Yogi, said, “In his long political career, Yogi was always a seer. He would look at the root of problems and try to solve them. Now he destroys the opposition—not the cause of the opposition. From a leader of Hindus, he has turned into a leader of only Thakurs. Not many will say that. But I am neither afraid of being targeted nor of being killed. In all his years as chief minister, not once has he said anything remotely spiritual. Instead, his language now consists of words like thok do.”

Also read

- UP CM Adityanath, Union Minister Jitendra Singh to visit Lucknow CSIR Start Up Conclave on September 15

- Yogi Adityanath cites Ramayana to target SP in Assembly speech

- Uttar Pradesh: 11 devotees dead in Shahjahanpur as truck full of gravel overturns on their bus

- Yogi pushes for Ayodhya in 2047; says there is 'no paucity of funds'

- We doubled UP’s per capita income, made it India’s second-largest economy

- New investment has brought in employment

Thok do, loosely translated to shoot them/bring them down, is a reference to Yogi’s policy of zero tolerance to crime. “Thok do is a colloquial term,” said Vikram Singh, former director general of police. “It gives a signal to the police force to go after criminals and annihilate them. He (Yogi) inherited a state that was on fire. Never was there such an unambiguous signal to criminals that they will not be tolerated. There is no complicity of the top most seat of authority (the CM) with the underworld. However, the weakness that must be tackled is the apparent lack of supervisory control over the police, for example in the case of the Mahoba superintendent of police (accused of abetment to suicide and corruption).”

A common perception is that while the chief minister himself is well-intentioned, he is surrounded by advisers and officers who give him ruinous advice—be it the filing of FIRs against journalists or the hurried, nightly cremation of the Hathras gang-rape victim. The administration is also often guilty of disregarding what he says. One of the most powerful examples of this is that despite his repeated orders that telephones should always be answered, they are very often not. Among his own party members, there is great heartburn over the fact that neither ministers nor bureaucrats pay any heed to them. And despite the emphasis on digitisation and elimination of human discretion, bribes have not been eliminated.

Shantanu Gupta, author of The Monk Who Became Chief Minister: The Definitive Biography of Yogi Adityanath, said that the nature of his political rise (through the Hindu Mahasabha and the Hindu Yuva Vahini, and not the RSS) was responsible for the time it was taking for him to build a trusted network of advisers within the bureaucracy and the party. “There is an Amit Shah for the PM,” he said. “Yogi ji is yet to have that person to fall back upon.”

Gupta also said that though Akhilesh Yadav and Yogi were about the same age (Yogi is just a year older), the latter was never referred to as yuva neta (young leader)—a title also generously offered to Rahul Gandhi, two years Yogi’s senior. “After his second term as CM, he will have a political resume matched only by Devendra Fadnavis (former Maharashtra CM) or Smriti Irani (whose defeat of Rahul Gandhi in Amethi was historic). The BJP gives ample opportunity to performers,” said Gupta in reference to the possibility of Yogi becoming prime minister.

This likelihood is painted in harrowing terms by some parts of the media, with his rise being projected as a certain death knell for minorities. Athar Husain, director of the Centre for Objective Research and Development, Lucknow, said that while there was “no doubt” that minorities were scared under the present regime, this was not an emotion that had developed “overnight” but was the result of the “failure of secular politics”. “For these parties, the question is always about just adding to their vote banks, not uniting society,” he said. “They are guilty of massive appeasement. This government might not have done anything anti-minority, but it is generally indifferent to them. It connects the overall culture of Muslims to the Mughals and uses it to rename cities and institutions, when the fact is that hardly 2-3 per cent of the Muslim population came from outside the country.”

Muslims, in turn, have been turning away from democratic processes, added Husain. “Where are they in the farmer protests, for example? They only come out for something like the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, which they feel threatens their very being,” he said. “We have a democracy based on first-past-the-post system, but that does not mean that such a large proportion of the population (minorities) can be ignored and belittled.”

Mohammad Nasir, assistant professor (law) at the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), said that governance has to be segregated from politics. “In so far as governance of social sector welfare schemes of the UP government is concerned, there seems to have been no demonstrable grievance or evidence of discrimination against minorities,” he said. “In fact, government data shows a large number of minorities to have been beneficiaries of various programmes. While the BJP may not need Muslim vote politically, it certainly realises that the state cannot progress without them being on board in initiatives for economic and human development betterment.”

Nasir cited the participation of the prime minister at the centenary celebrations of AMU as a genuine attempt by the government to have an outreach and dialogue with the Muslims. “It is notable that a university situated in UP was chosen as a platform to convey a message to not only Muslims in UP and India, but abroad as well,” he said. “By labelling AMU as a ‘mini India’, the prime minister etched the university as a microcosm of the Indian society and a unique symbol of India’s composite culture. These words are also an indicator to tone down the polarising electoral rhetoric. That this toning down message was delivered in UP and with little over a year due for the assembly elections is significant.”

One illustration of the administration of schemes for the most vulnerable lies in the number of houses allotted to scheduled castes and minorities under the PM Awas Yojana that provides affordable houses to the poor. Of the 14,46,083 beneficiaries of the scheme between 2016-17 and 2020-21, the number of minority beneficiaries was 1,62,751 while SCs got 5,07,596 houses. (SCs form 20.7 per cent of the state’s population and minorities 19.26 per cent) Governments, however, do not come with magic wands.

The simple question of how convenient it is to live in the state, for instance, is answered by the Ease of Living Index, 2020. This is described as a measure of “well-being of Indian citizens”. Not a single of the state’s seven cities with a population of over a million make it to the top 10 list; same goes for the below-a-million population category. Municipal performance similarly does not make it to the top in the first category of cities; Jhansi is the only one to figure in the second one. These are long-standing challenges that require time to tackle.

But politics does not offer the luxury of time.

In the life of a state, four years might be a small period. For Yogi, it might be too brief a period to learn the intricacies of the country’s most populous state. But to that tricky human gaze, it could seem like a lifetime. It is in that grey zone between an object and its image that the future of the state’s development and politics lies. For Yogi and his government, there is just under a year to mould that gaze.