The name Kameshwar Chaupal would not have rung a bell for many people, if not for the Supreme Court’s decision to pick November 9 as the day to deliver its historic judgment in the Ayodhya case.

On the same day 30 years ago, the Vishva Hindu Parishad chose Chaupal, a dalit kar sevak from Bihar, for laying the foundation stone of the proposed Ram mandir in Ayodhya. In the presence of saffron-clad monks, he laid a consecrated brick in a 7ft-deep trench near the disputed site.

The shilanyas changed Indian politics dramatically. In the Lok Sabha elections held weeks later, the BJP rode the mandir wave to win 85 seats, up from just two in 1984. Chaupal later joined the party, becoming a member of the legislative council in Bihar in 2002, and contesting the Lok Sabha elections in 2014 from Supaul, although unsuccessfully.

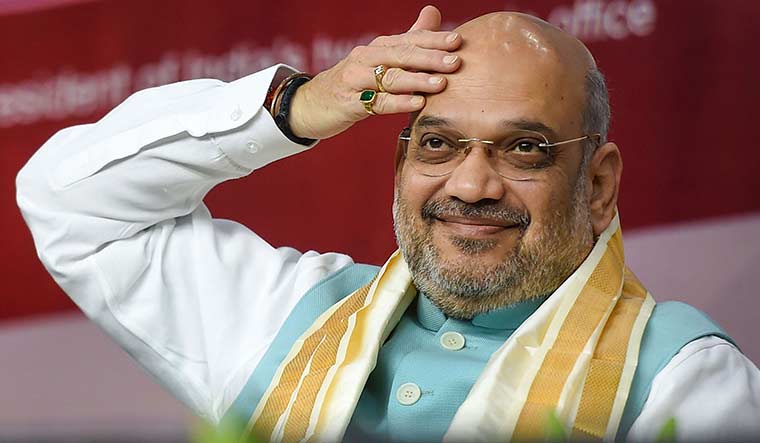

Thirty years since Chaupal laid the foundation stone, a five-member Constitution bench of the Supreme Court has finally allowed the faithful to construct a temple on the disputed site. The verdict is expected to give another fillip to the rightward shift in Indian politics, and it comes at a time when the mascots who led the mandir movement in its fledgling days—including L.K. Advani, Uma Bharti and Murli Manohar Joshi—have all faded away. The movement’s legacy, and the credit for the construction of the mandir, will be conferred on Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Union Home Minister Amit Shah, who are together changing the course of India’s polity.

If their launchpad was muscular nationalism, Modi and Shah have now unambiguously embraced hindutva politics. The Ayodhya verdict is in line with their mission to address the grievances and aspirations of India’s majority community. The verdict could also help coalesce the majority sentiment and lead to further consolidation of Hindu votes.

The changed reality is evident in the way the Congress and other opposition parties have responded to the verdict. Reluctant to be seen as siding with Muslims, the Congress has welcomed the judgment. And so have such leaders from the socialist stable as Nitish Kumar of the Janata Dal (United), Akhilesh Yadav of the Samajwadi Party and Mayawati of the Bahujan Samaj Party. An example of how the opposition is moving rightward can be seen in Maharashtra. After toying with temple visits and soft hindutva, the Congress has now moved on to post-poll parleys with the hardline Shiv Sena.

The shift has roots in the 1990s, which saw the rise of socialist and caste-based parties after the implementation of Mandal commission recommendations granting 27 per cent reservation in jobs and education to people belonging to Other Backward Classes. For years, the so-called Mandal politics ran parallel to the BJP’s mandir politics, which was fuelled by Advani’s rath yatra and the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992.

In recent years, though, the BJP’s mixture of hindutva and muscular nationalism have been winning elections and increasingly attracting OBCs and dalits—the backbone of Mandal politics. Nitish, Akhilesh and Mayawati’s responses to the Ayodhya verdict signal that mandir politics may have finally won the long-fought electoral race.

“The biggest change this judgment has brought about is that it has redefined the concept of Nehruvian secularism, which created a binary of Hindus and Muslims,” said Rakesh Sinha, BJP leader and Rajya Sabha member. “The response to the judgment has been muted, keeping in mind the social diversity of this country. It also marks the fulfilling of the long demand of Hindus, whose places of worship were destroyed by foreign aggressors.”

Sinha draws a parallel between Ayodhya and the Somnath temple, which was rebuilt in 1951. The old temple was said to have been destroyed several times by marauding armies centuries earlier, even though no mosque was built on the spot where the temple stood.

“Ram Janmabhumi is an extension of Somnath, but more at a mass level,” said Sinha. “The Somnath debate was among the elites of that time—Jawaharlal Nehru on one side and K.M. Munshi, Rajendra Prasad and Sardar Patel on the other. The delay in resolving the Ram Janmabhumi tangle worked in our favour. Had it been resolved in 1949, it would not have awakened the masses. This awakening led to debates on the issues of nationalism, hindutva and secularism on a mass level.”

Also read

- Ayodhya's traders turn to Hanuman to rescue them from being uprooted for the Ram temple

- Ayodhya Ram Mandir's garb griha has a Muslim connection

- ‘Don’t donate silver bricks, bank lockers have no space’: Ram Mandir Trust

- Land ownership plea not related to Dhannipur, says official

- Work on laying foundations for Ram temple in Ayodhya to begin after Dec 15

- A(Yodh)Ya—The land of no conflict

- Ram mandir: Digivijaya sharpens attack on PM Modi over 'inauspicious mahurat'

The beneficiary of these emotive debates has been the BJP, even though the electoral impact of the mandir movement itself remains debatable. The party could win just over 50 seats in the 1991, 1996 and 1998 Lok Sabha elections. Also, it fared badly after the Vajpayee era, when the original mandir mascot Advani took over. The BJP had to wait till 2014 for a resurgence.

The verdict will cement Modi’s image as ‘Hindu hridaysamrat’. He has fulfilled two long-pending demands of the saffron brigade—the revocation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status and the construction of the Ram mandir. But closure still eludes festering issues like the implementation of the National Register of Citizens in Assam and the demand for a uniform civil code. Helping Modi and Shah push forward, however, is the reluctance of opposition parties to take a decisive stand on issues that matter.

The Supreme Court has entrusted the Union government with the task of forming a trust to start the temple construction. Shah is expected to play a key role in the formation of the trust, and may even aid the construction. Modi, who organised Advani’s rath yatra as a BJP functionary, is expected to project the building of the temple not just as a symbol of Hindu pride, but also as a cultural and national event.

The Ayodhya judgment aids Modi in other ways as well. It gives political leadership supremacy over spiritual leaders—that, too, in a religious issue. The inclusion of dalit members in the trust will send a larger political message that the temple construction is an inclusive Hindu initiative. All eyes will be on the new Chaupal.

The BJP and the RSS have ordered supporters not to indulge in triumphalism, but it is clear that the verdict will form the subtext of all future election campaigns. Soon after the judgment, BJP general secretaries Ram Madhav and Kailash Vijayvargiya went to Kolkata to visit the homes of the Kothari brothers, who were killed in the 1990 firing in Ayodhya. There have been demands for declaring them martyrs and building memorials for them.

The assembly polls in Jharkhand later this month, and in Delhi and Bihar next year, are likely to witness the BJP using the Ram temple card. The party would be aiming at consolidating Hindu votes to override the fallout from the slowing economy.

Concerns have been raised about the growing influence of majoritarian sentiments, but the government has largely silenced the critics. “There is a difference between running a majority government and a majoritarian government,” said Manoj Jha, Rajya Sabha member and Rashtriya Janata Dal leader. “The former takes into account diverse opinions, but the latter just bulldozes other arguments, as it has happened in Parliament.”

The homogenisation of public opinion has brought about another tragic change. Muslims feel they can no longer influence elections. Muslim voters used to influence results in at least 115 Lok Sabha seats. In at least 30 of these seats, they were the dominant community. But now, with the BJP’s increasing success in consolidating caste votes, Muslim voters have become marginal players. Elections are now decided on the share of Hindu votes—as seen in Madhya Pradesh, where the Congress used soft hindutva to oust the ruling BJP last year, and in Haryana, where Congress leader Bhupinder Singh Hooda openly supported the BJP for revoking Jammu and Kashmir’s special status.

There is anguish among Muslims over the Ayodhya verdict, but they are under pressure to move on. Muslims leaders have called for maintaining peace and harmony, as they decide on whether to accept the five acres in Ayodhya that the Supreme Court has offered as restitution.

Sustaining the current narrative—that there are no winners and losers with regard to the Ayodhya judgment—will depend a lot on how the BJP and the RSS continue to rein in hotheads. “The talk of majoritarianism is anathema to Indian ethos,” said Sinha. “Hinduism, by its nature, cannot be majoritarian, as it celebrates diversity. [The claim that hindutva is majoritarian] is often spread by Left historians and thinkers, who see that they are losing ground. Modi represents the thought that the country should look at indigenous concepts of secularism rather than the European ones.”