In March, controversy brewed over Surf Excel's Holi advertisement which showed a Hindu girl protecting her Muslim friend from the colours being flung all around. The campaign received a lot of flak; this was normalising 'love jihad', right wing Twitter users argued. Social media lit up with hashtags for and against the ad. A French security consultant, who goes by the handle of Elliot Alderson on Twitter, studied the trend and made a very interesting discovery: 17 to 20 per cent of the tweet volume was driven by the IT cells of the BJP and the Congress. This was how disinformation worked in the 21st century, he wrote.

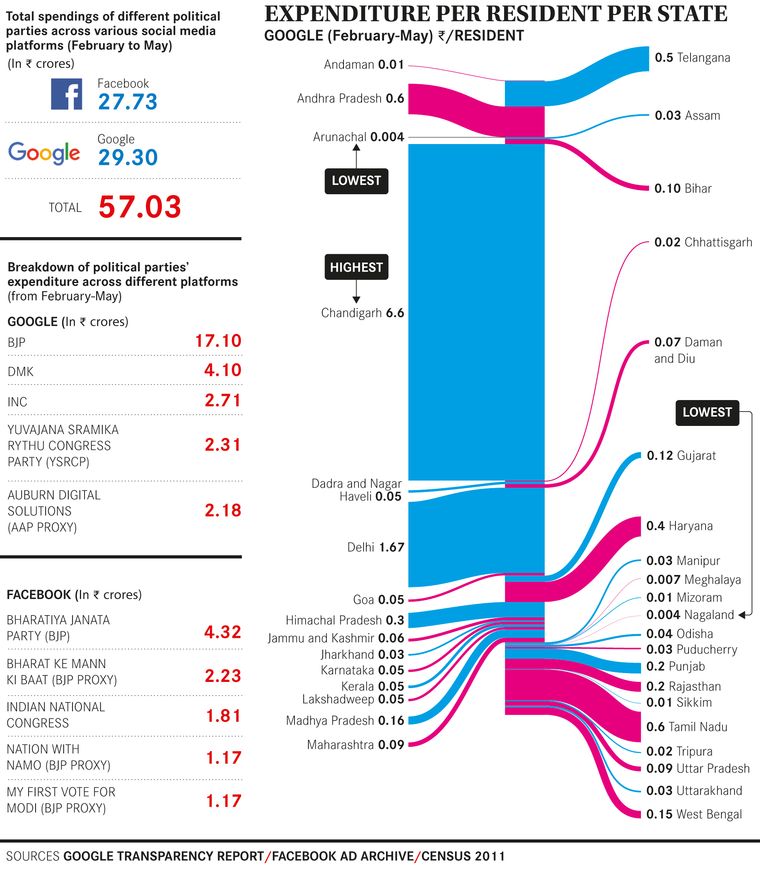

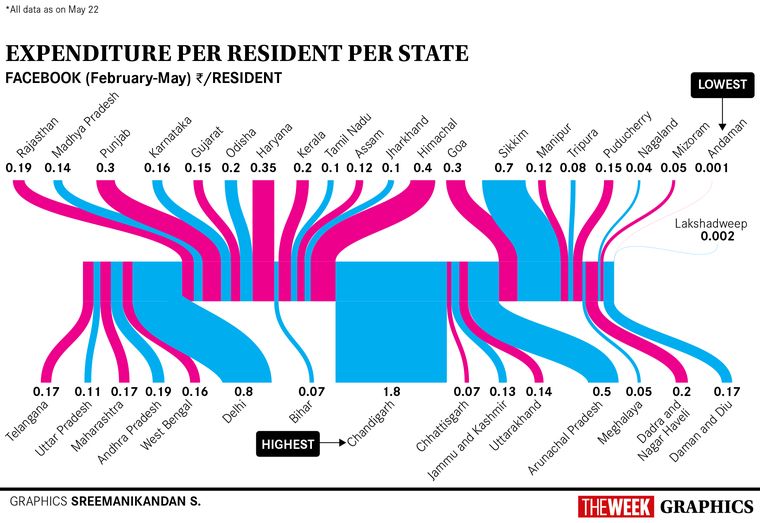

Social media polarisation, especially during elections, has reached its zenith. This is, in no small reason, thanks to the political parties who have pumped in huge sums of money for propaganda and voter outreach. In 2019, a total of Rs57 crore was deployed on Facebook and Google platforms—with the BJP spending the lion's share—for political ads [see graphics for details]. On Google, the BJP's spend was four times that of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), which came in at a distant second. Four of the top five spenders on Facebook were the BJP and its proxies. The 2019 Lok Sabha elections have been dubbed as India's first 'WhatsApp elections', taking into consideration the impact, mobilisation and spread of fake news on the 200 million-strong messaging platform. And, underestimating the impact of the holy trinity—Facebook, Twitter and Google—comes with its own perils.

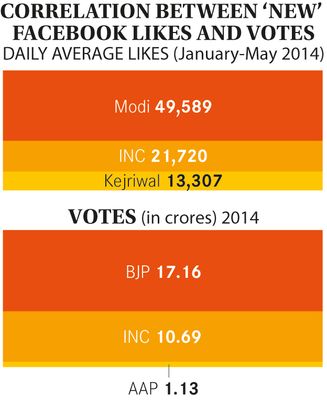

According to a study, Facebook ‘Like’ as a Predictor of Election Outcomes, published by the Asian Journal of Political Science in 2014, positive correlation could be established between Facebook likes for a candidate during an election campaign and the number of votes they received. In the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the hypothesis was put to test with the Facebook pages of Narendra Modi, Arvind Kejriwal and the Indian National Congress. It was found that Modi garnered the highest daily average likes during the campaign period, followed by INC and Arvind Kejriwal—49,589, 21,720 and 13,307 respectively. The votes they received were proportional. The BJP won the most votes among the three parties (17,16,37,684), followed by the Congress (10,69,35,311) and the Aam Aadmi Party (1,13,25,635). “The proportion of the average number of ‘likes’ recorded by the parties on Facebook—BJP (58.60 per cent), Congress (25.67 per cent), and AAP (15.73 per cent)—were very much in line with the election results.”

The effect of such campaigns should not be taken lightly, says Francis P. Barclay, the head of media and communications at the Central University of Tamil Nadu, who was involved with the study. "This is not a single post that we are talking about. Such relentless bombardment will have an effect on the decisions of the voter," he says.

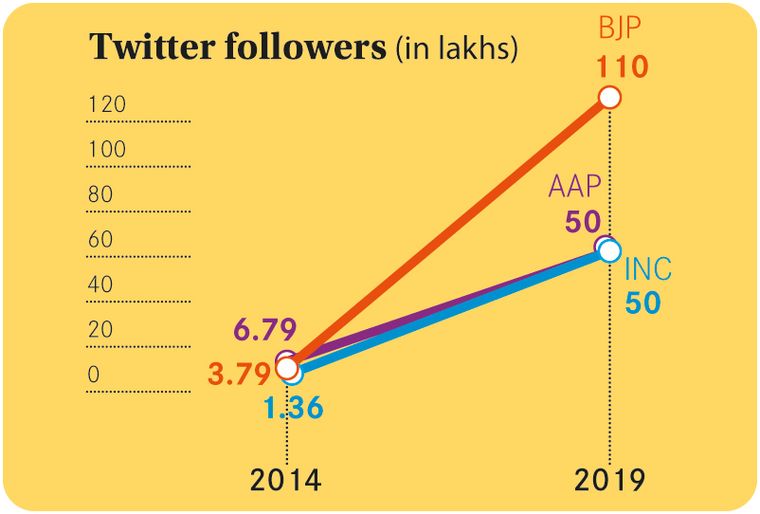

But, this was not always the case. Even in 2016, social media was nascent in the country; India had only 290 million smartphone users and 409 million internet users. As researcher Neena Talwar Kanungo from Indira Gandhi National Open University found in a study, as of March 2014, the AAP had 6.79 lakh followers count on Twitter, followed by the BJP with 3.79 lakh, and the Congress with 1.36 lakh. Now, the situation has changed completely. The number of smartphone owners and internet users has skyrocketed—estimated to touch 47 crore and 73.5 crore respectively by 2021. The BJP now boasts over 1.1 crore followers, the Congress has over 50 lakh, and the AAP a little less than 50 lakh.

All this has led to a social media churn on an exponential scale. The pendulum has swung all the way to the other end, says Barclay. "Earlier, these [social media platforms] were blindly trusted sources of information. Now, our research finds large sections of the public are very cynical. They refuse to believe even news that is true if it is on social media." The same reason—the growing inability to cut through the clutter—could also be why parties and proxies are increasingly relying on eyeball-grabbing fake news. In the digital space, the BJP had an early headstart. In 2019, how are the rest of the parties faring? "Gauging by the numbers, I would say it is a level playing field," says Barclay. "Now, you have to look at these [online campaigns] on a case-to-case basis. Whoever can spend the most has the upper hand," he says. Thus began the 2019 'race-to-the-bottom' campaign, clogging up an already unsanitary digital ecosystem. Jency Jacob, the managing editor of fact-checking portal BoomLive, said he was taken aback by the scale of false content generated in the aftermath of Pulwama suicide bombing in February. "We were on the lookout, but could not anticipate the flood of misinformation. Why would anybody make up false videos of the widows of the martyred soldiers?" he asked. Then there are political parties using proxies to bypass the Election Commission's cap on online campaign expenditure [see graphics]. "Measures like the [political] ad archive set up by Facebook are commendable," says AltNews co-founder Pratik Sinha. "But, there are issues. Take the case of [BJP proxy] Nation with NaMo. It provides no details on what this entity is."

Also read

- Modi returns

- Modi and Amit Shah pave way for saffron sequel

- Rahul Gandhi handcuffed by Modi juggernaut

- The Winners…........& the Losers

- Lok Sabha elections 2019: U.P's changing voter profile

- BJP and Shiv Sena: An effective force

- Modiji was most effective

- Modi, BJP have entered Mamata's backyard

- Karnataka: Modi, BJP look to topple coalition government

- B.S.Yeddyurappa: The coalition has flopped

What we have ended up with, arguably, is a Frankenstein's monster. "Our latest research has shown that, far from being a weapon [for the establishment], this [the campaign machine] could ultimately turn [on the masters]," says Barclay. "Our data shows that people are losing faith in the institutions, and this is ultimately leading to the retrogression of democracy itself."