There were two strong sentiments across Uttar Pradesh, throughout the seven-phase election. The first was that the country’s international stature had grown in the aftermath of the Balakot air strike. The second was the perception that everyone in the state had something—be it a gas connection or a toilet—and that something was better than nothing. As the results unfolded, it seemed that though the state’s principal opposition of the Bahujan Samajwadi Party-Samajwadi Party-Rashtriya Lok Dal alliance (mahagathbandhan) and the Congress had read these sentiments, it had not gauged their severity.

The foundation for BJP’s 2014 encore in the state could have been laid in the loss of the 2018 byelections, in which the party lost the seats of Phulpur, Kairana and Gorakhpur. In its immediate aftermath, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) lent greater urgency to its activities in the state. There was a rapid increase in the number of shakhas—especially in the east and west. Booth-level coordination committees were set up and members fanned out to spread word about central government schemes, while ensuring that the dalit and OBC vote remained within the party fold.

The state’s results are a definite nod to its changing voter profile, which does not respond to older caste templates. First-time voters and women do not seem to have bowed to family and community diktats. A senior SP leader from east UP told THE WEEK: “Large parts of the state have electricity for the first time. If entertainment is more accessible, so is the news. Aspirations are realigning.”

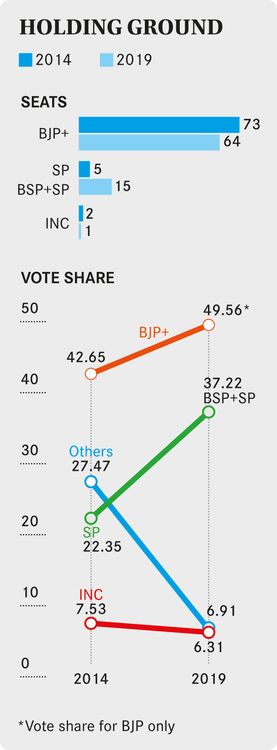

For both the SP and the BSP, this result poses tough questions for the road ahead. Their alliance was based on the math that two parties together would poll 42.27 per cent of the vote (their combined strength in 2014) and would thus touch the BJP’s tally of 42.63 per cent. That arithmetic discounted the results of the 2017 assembly elections, in which the BJP won its highest ever count of 325 seats. The alliance was seen as a cobbling together of leaders, but not of workers. Yadavs and dalits have not been historical allies, and over the long-drawn electoral process, the differences among party workers surfaced. There were even reports of them coming to blows.

The other great gap in the alliance strategy seemed to have been a complete absence of focus on smaller caste groups within the SC and OBC umbrella. Said an SP insider: “We had no strategy for [these groups] when it is in fact they who decide the swing in the votes. They voted for the BJP solely on the Hindu card and we were unable to stop them.”

In the case of the BSP, there is a definite questioning of the party’s foundation. Sarwan Ram Darapuri, a dalit social activist, said: “The BSP’s core vote is cracking. On the issue of landlessness, for instance, which impacts dalits most deeply, there is very clear anger over [Mayawati’s] lack of action. There is also growing realisation that those who get tickets from the party are not allies of the dalit cause. The party and, by extension, Mayawati are no longer seen as the vanguard of dalits.”

The BSP pitch this time emerged as one that was subtly crafted around the possibility of a big role for Mayawati in the Centre. This was a perception fed into by Akhilesh Yadav. The subtext was that with Mayawati out of the state, the SP could consolidate its battle plan for the 2022 UP assembly elections.

For the SP, questions about the future are also aligned with posers on Akhilesh’s strategy and leadership. The gaggle of advisers who surround Akhilesh are seen to be out of touch with ground-level equations. The party’s broad-based leadership built by Mulayam is no longer visible. There is also rising disapproval of the manner in which the Yadav family itself does its politics. In Kannauj, for instance, the electorate voiced its disappointment with Akhilesh’s wife Dimple for never visiting the constituency after her 2014 win, and she lost. This is in contrast with how Smriti Irani nurtured Amethi despite losing in 2014, which resulted in Rahul Gandhi’s dethroning this time.

Also read

- Modi returns

- Modi and Amit Shah pave way for saffron sequel

- Rahul Gandhi handcuffed by Modi juggernaut

- The Winners…........& the Losers

- BJP and Shiv Sena: An effective force

- Modiji was most effective

- Modi, BJP have entered Mamata's backyard

- Karnataka: Modi, BJP look to topple coalition government

- B.S.Yeddyurappa: The coalition has flopped

- Kerala: Congress thwarts Modi, BJP wave

The question on which alliance member is the bigger loser has not been answered definitely. However, for the SP, there seems to be greater danger of its Yadav vote making a shift. The BSP’s core Chamar-Jatav vote could prove to be relatively more stable as they may take time to choose a political alternative. But young and first-time voters on both the sides have exhibited a mind of their own, not preconditioned by the caste structures and boundaries set by its earlier generation.

BJP’s state general secretary Vijay Bahadur Pathak sees the party’s victory as its growing appeal across all castes and religions. “Take the issue of triple talaq. How can one say that no Muslim would have supported the party over it? The voter saw the gap between what it could not get in many decades and the possibility of what more it could get by voting for Narendra Modi,” he said.

The state has made sharper the Congress’s dilemma of how it must position itself. In 2014, its hope that the Muslim and dalit vote would see it through tanked as even its traditional upper caste voters deserted it and the party was reduced to two seats. Its alliance with the RLD, too, did not help. This time, the Congress was kept at bay by the grand alliance. The view that Priyanka Gandhi Vadra entered the scene too late to take charge of east UP is also being put forth; there will be questions whether her presence helped at all.

“In close to 20 constituencies, we gave tickets to those who had joined us only before the elections,” one senior party leader told THE WEEK. “The voter was smart enough to realise that such candidates were not in the party for the long haul.”

The state has sent out some clear signals. One, that it is not mathematics but chemistry which works for alliances. Two, that there are no holy cows in politics and family bastions can crumble. Three, castes can realign and recombine in unexpected ways. Four, charisma remains a decisive factor for the electorate. And five, local issues such as the stray cattle menace, though powerful, are kept aside in a national election.