The toast is no longer with tea.

Five years ago, on a May morning when Lok Sabha election results were coming out, thousands had thronged the BJP’s decrepit offices on Ashoka Road in New Delhi. There they celebrated with pots, kettles and cups of syrupy tea, their champagne of victory over an old order that had been snootily keeping chaiwalas and the likes of them out of the elite world of Lutyens’ children.

Much water has flowed down the Yamuna and the Varanasi Ghats of the Ganga since then. The BJP head office is now located in a five-storey, centrally-cooled chrome-glass-and-concrete structure on Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Marg. It has swanky cafeterias from where, on Victory Day this year, hundreds of party workers were seen picking up packaged drinks and foil-wrapped short eats. Hawk-eyed guards kept them off the grass in the central courtyard, and janitors kept the place neat and tidy even on a day of boisterous victory.

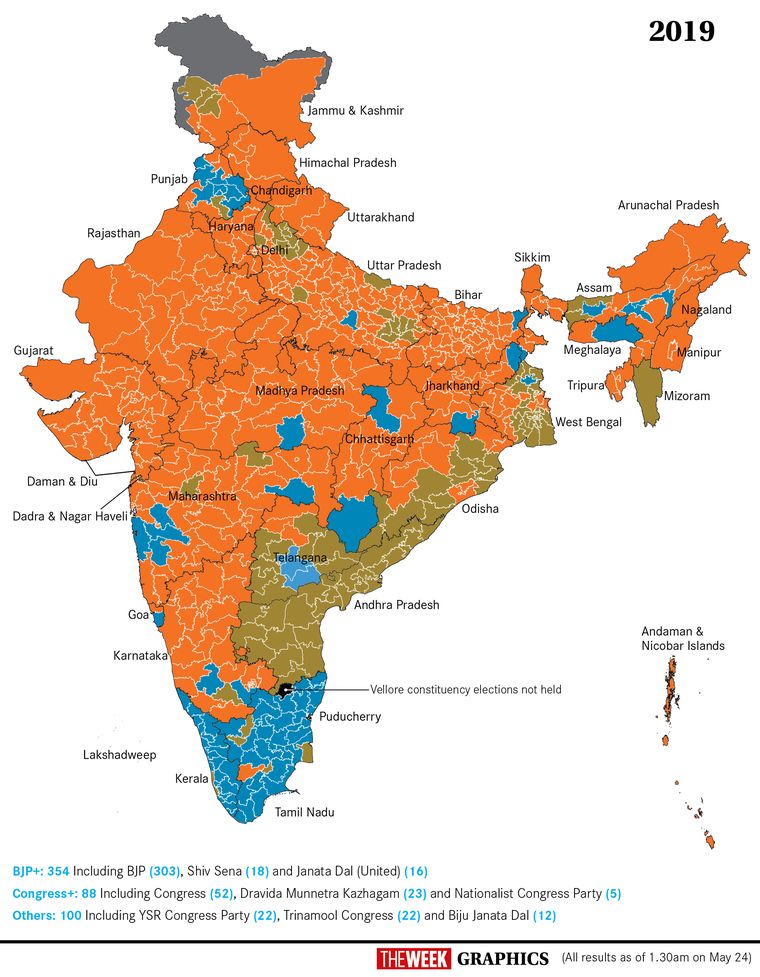

In five years, the BJP has changed, and so have India and India’s politics. The old and soiled politics of poverty and patronage, practised through promises of bijli, sadak, paani and primary schools, has given way to a new politics—the politics of aspirations, practised through promises of bullet trains, escalators, power bikes, big cars, cheap flights, IITs, smart cities and a matching national machismo.

Unlike in 2014, Narendra Modi didn’t talk much of these during his campaign this time. Over the last five years, he and his partymen had been talking about having delivered these goodies—may not be in my village, but definitely in his town, her village or their city. India, the voter believed, was changing under Modi, and if change hadn’t yet come to his village, he will wait for it.

Also read

- Modi and Amit Shah pave way for saffron sequel

- Rahul Gandhi handcuffed by Modi juggernaut

- The Winners…........& the Losers

- Lok Sabha elections 2019: U.P's changing voter profile

- BJP and Shiv Sena: An effective force

- Modiji was most effective

- Modi, BJP have entered Mamata's backyard

- Karnataka: Modi, BJP look to topple coalition government

- B.S.Yeddyurappa: The coalition has flopped

- Kerala: Congress thwarts Modi, BJP wave

That is another change. Perhaps for the first time, the Indian voter is showing patience. Patience with a leader who may not yet be delivering but who, they believe, can deliver.

It is this faith of the voter—that they have a leader who can—that has worked so overwhelmingly for Modi and the BJP. The voter has seen it at work in Balakot. The opposition and the sceptical media may argue, till the sacred cows come home, whether he did hit there or not. But the voter believed that he did, because he is a leader who can.

That perhaps marks another epoch-making change in Indian politics. After years of electoral scepticism, despondency and a sab-chor-hai sentiment, the voter has come to believe that electoral politics can still transform his and his country’s destiny for the better. Finally, he has come to have trust in politics which used to be dismissed, in middle class chatter, as a scoundrel’s last resort.

The opposition would continue to say, and so would the wise men of the old order including large sections of the media, that Modi has been creating a make-believe world. That jobs aren’t actually coming, that businesses aren’t actually doing well, that Balakot wasn’t actually hit, that Rafale was actually a sellout. Now the big challenge for Modi is to prove that he can actually deliver, and live up to the trust that the voter has shown in him, in his party, and in electoral politics that was perceived to be once a cesspool of corruption.

The first few months of the new regime would be fairly easy. As Modi himself has claimed, he has brought several of the corrupt to the doors of the prison. It would be fairly easy for him to kick them into the prison cells, and claim to be waging full scale his long-promised war on corruption. It may look vindictive politics to many, but the odds are that Modi will go for the kill on this front.

But hunting down the corrupt and hitting at the Balakot baddies are the easier among the tasks ahead. The biggest tasks, rather challenges, would come after that. More difficult would be to repair the economy which, as the opposition and the wise men of the old order have been alleging, is doing badly. Jobs will have to come sooner than later; growth will have to be restored to the old pace of 8 per cent; small businesses will have to be salvaged from the note ban and GST mess; farmers will have to get better incomes; bullet trains will have to run.

And it won’t be an easy run, either. The opposition may look decimated now. They could be less vicious in the Lok Sabha, but they could still derail several of his reform measures in the Rajya Sabha. Moreover, as many political thinkers point out, if the opposition does not get its voice heard in the portals of Parliament, there is always the streets where anger and resentment could burst out against regimes.

It all would depend on how Modi and his party interpret the new mandate. They could view it as a consent given by the voter to pursue their majoritarian politics, ride roughshod over the opposition, overwhelm the minorities, and play macho politics. Modi’s politics till now has been one of ‘streetsmartness’—a kind of politics with rough edges and sharp points, one that has been injuring the opposition, rather than softening the opposition.

But, if he chooses, the renewed mandate could also be viewed as a trust, reposed in him and the BJP, for building an aspirational India of IITs, rocket scientists, bullet trains, smart cities and water-flushed toilets. For that, a wiser option would be to play the accommodative ruler, one who softens the opposition rather than injures the opposition.