Scientists have created the world's smallest stent—40 times smaller than any produced to date.

Stents have been used to treat blocked coronary vessels for some time now, but the urinary tract in foetuses is much narrower in comparison, said researchers from Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH Zurich), Switzerland.

About one in every thousand children develops a urethral stricture, sometimes even when they are still a foetus in the womb.

In order to prevent life-threatening levels of urine from accumulating in the bladder, paediatric surgeons have to surgically remove the affected section of the urethra and sew the open ends of the tube back together again.

It would be less damaging to the kidneys, however, if a stent could be inserted to widen the constriction while the foetus is still in the womb, according to the study published in the journal Advanced Materials Technologies.

It's not possible to produce stents with such small dimensions using conventional methods, which is why paediatric surgeon Gaston De Bernardis from Aargau Cantonal Hospital approached the Multi-Scale Robotics Lab at ETH Zurich.

The lab's researchers have now developed a new method that enables them to produce highly detailed structures measuring less than 100 micrometres in diameter.

"We've printed the world's smallest stent with features that are 40 times smaller than any produced to date," said Carmela De Marco, lead author of the study.

The group calls the method they have developed indirect 4D printing.

They use heat from a laser beam to cut a three-dimensional template—a 3D negative—into a micromould layer that can be dissolved with a solvent.

Then they fill the negative with a shape-memory polymer and set the structure using ultraviolet (UV) light.

In the final step, they dissolve the template in a solvent bath and the three-dimensional stent is finished.

It's the stent's shape-memory properties that give it its fourth dimension. Even if the material is deformed, it remembers its original shape and returns to this shape when warm.

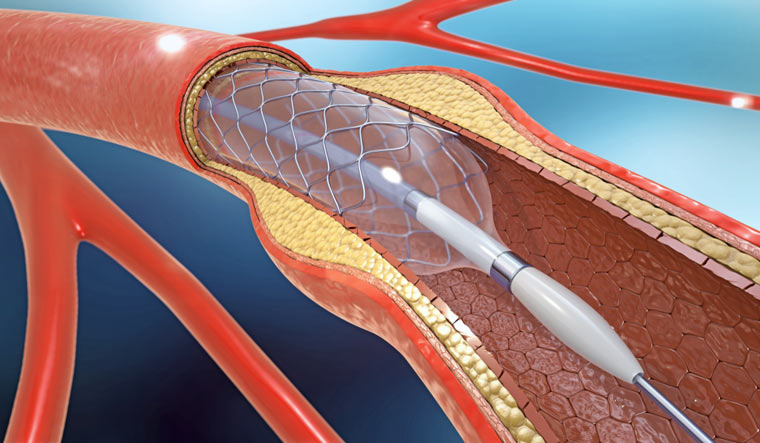

"The shape-memory polymer is suitable for treating urethral strictures. When compressed, the stent can be pushed through the affected area. Then, once in place, it returns to its original shape and widens the constricted area of the urinary tract," De Bernardis said.

However, the stents are still a long way from finding real-world application, researchers said.

Before human studies can be conducted to show whether they are suitable for helping children with congenital urinary tract defects, the stents must first be tested in animal models, they said.

"We firmly believe that our results can open the door to the development of new tools for minimally invasive surgery," De Marco said.