The atmosphere is saturated with anticipation as a group of nurses keep passing files. The astringent scented corridor has many stories floating around, both good and bad. A couple in their early thirties walk past the chaos into an isolated ward. It is their third time at the pre-natal screening unit. They take a deep breath as the attendant hands them their report. They whisper a prayer before they opened the envelope. Thalassemia major, the report confirms. Their hands tremble as they fill out the consent form for termination of pregnancy for the third time. And then, without saying a word, they walk out of the ward, back into the chaotic corridor where their agony is just another poignant story. The question is, can their story have a happy ending?

Despite the massive campaign against abortion, most parents who get to know about some form of deformity in their unborn child tend to terminate pregnancy prematurely. As per the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) act of India, abortion can be performed on various grounds until 20 weeks of pregnancy. But what is the right thing to do? Is it fair to give birth to a life of suffering in the run to be ethically right?

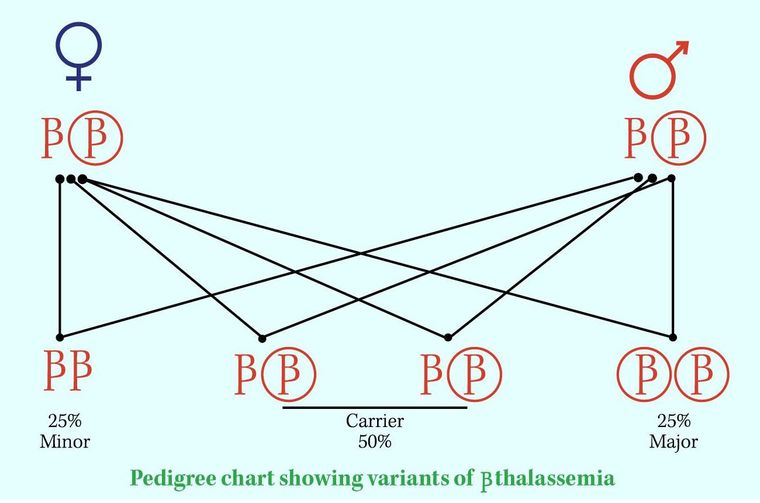

Says Dr Mathew Pappachen, CEO of Reproductive Genetics and Cancer Solutions (RGCS), a division of Lifeline hospital in Kerala: “In some cases, when the parents know that they are thalassemia carriers or have a family history of the condition, they do a screening test to check whether the foetus is affected. This information can be made available as early as the 14th week of gestation. There is a 25 per cent chance that the child is normal. Sometimes parents choose to terminate pregnancy if the foetus is found to have thalassemia major. Pregnancy is allowed to proceed to term if the baby is either normal or has thalassemia minor. If, on the other hand, the foetus has thalassemia major, the family is informed of the situation and the challenges involved with it. Decision of the fate of the gestation will, however, rest on the parents.” Isn’t it better to terminate the foetus in the womb rather than let it suffer after birth? But isn’t this the same as murder? Is this the only option?

They say, there is some form of elimination in every process of life. But having said that, correction greatly outweighs deletion, says Dr Sreelatha Nair, who is also part of RGCS. “After years of research, doctors have found that bone marrow transplant cures the condition to a large extent. Finding a match for the transplantation is, however, difficult. This is where the ‘saviour sibling programme’ comes in,” she says.

Surely, there are many debates around the ethical aspect of this programme but most of it is due to ignorance. Though the first savior sibling programme was done in the US in 2000, it got attention only after Jodi Picoult published the book My Sister’s Keeper, in 2004, and also the launch of the movie based on it. But, in contrast to the actual procedure, the savior sibling in the book and the movie keeps on helping her elder sister throughout her childhood, including an organ transplant, rather than a one-time umbilical cord donation. It also got some light when a couple in the UK went for a legal fight to get permission to undergo the procedure in order to save their elder son who had beta thalassemia.

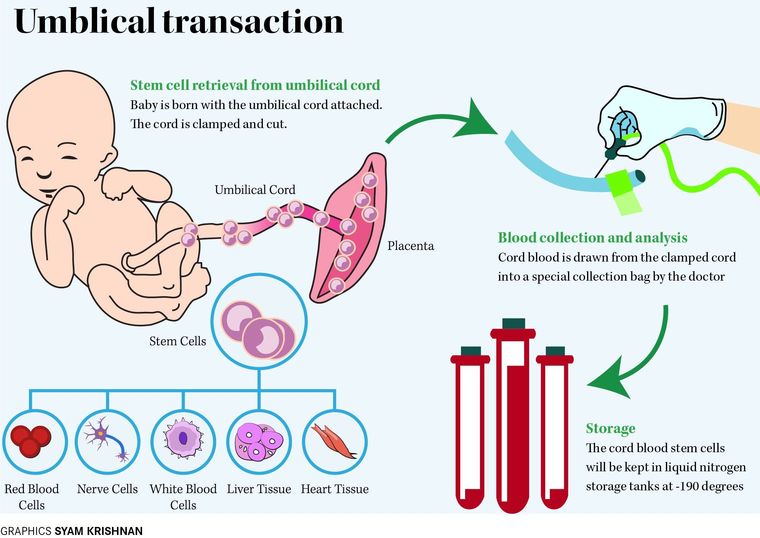

Most people have the notion that the younger sibling is killed in the process of saving the elder one. The only bloodshed that happens in the process is during the delivery of the child. The process involves implantation of the unaffected embryo, which is fertilised in-vitro, in the uterus. With the help of pre-implantation genetic diagnosis and IVF techniques, a cell from the specially selected embryo is checked to see if it is disease-free and a good match. Once the match is found, the embryo is implanted into the mother's womb and she is allowed to proceed to full gestation. The stem cells are removed from the newborn's umbilical cord at the time of birth and transplanted to the older sibling suffering from the genetic disorder. Once transplanted, the older sibling's ailment is cured. Using this technique, the affected elder sibling will have an 80 per cent chance of a match being found, compared to a 20 per cent chance from a brother or sister conceived naturally.

Then, what is all the noise about? The fact that there is no consent from the child to take the stem cells, is one argument, though it might sound childish to some. Another point raised is the exploitation of this technique to create designer babies. But in a world of ‘designer everything’, is it a cardinal sin?

Despite the many arguments against this process and doubts on the welfare of the savior sibling, doctors and researchers across the globe vouch for it as it can eradicate several genetic disorders and improve the quality of lives of the ones affected with it. Surely, there is a certain uncertainty linked with the future of this programme and ways as to which it can be exploited. Nonetheless, it is a way to help ease the suffering of the affected persons and their kin. Alleviating suffering justifies almost anything and probably, 'all is fair' when it comes to ways to do it.