A little bit more brittle and a little bit more brownish. Akansha Deo Sharma, 28, is trying to describe the texture and colour of rice straw.

Rice straw, or the crop waste from paddy fields, is popularly seen as being at the heart of the annual phenomenon that results in Delhi having the worst air on the planet—stubble burning; relentless amounts of which cause deadly levels of air pollution in the National Capital Region.

As Ikea’s first and only Indian in-house designer, Akansha was presented with the material as part of the Swedish furniture company’s 2018 “Better Air Now” initiative. Deciphering the much-reviled residue was a bit of a challenge. How do you dye it? How would one incorporate cotton? How does one beat it to a pulp so it can be mixed with cotton waste?

But, she eventually realized a neat little set of homeware items in soft blue, grey white and indigo—think lampshades, rugs, table runners, placemats, and many kinds of bowls—as part of the Förändring ("change" in Swedish) collection, where every product is made of rice straw in varying proportions.

"I think what was fascinating about working with this material was to explore this technique called moulding. Here we had tried different iterations of rice straw pulp—[keeping in mind] how it would look, how stable it would be and what its texture would look it? We experimented with different ratios [of pulp], from 100 to 80 to 60/40 and 40/60, but we were very clear that we did not want a lesser proportion of rice straw. We wanted to highlight and celebrate this material," says Akansha.

Förändring will be rolled out in stores around the world in January. She mentions the recent launch of air-purifying curtains called Gunrid, available now, as the company takes the next leap to design the future of domestic life. "The whole collection (Förändring) is a big statement on the part of Ikea."

All global, hard-charging companies have secret innovation labs employing thousands of people to research and develop the next breakthrough product. Ikea's "future-living" lab Space10 set up shop in Delhi last month. Space10 is Ikea's not-so-secret design and research lab in a meatpacking district in downtown Copenhagen.

A man painting the Space10 logo onto a wall in Hindi

A man painting the Space10 logo onto a wall in Hindi

Started in 2015 by a group of four founders, Space10 now has a core team of 30—with specialists and creatives employed from backgrounds as diverse as aerospace engineering to psychology, anthropology and journalism. They brainstorm future solutions to major societal changes likely to affect the planet.

To this end, they have vertical hydroponic farms in their basement to playfully test and grow future food—a bioreactor for spirulina, an insect farm for mealworm and an aquaponic system for fish and plants, producing tons of alternative ingredients and sustainable recipes.

Innovative concepts are explored here in staggering variety. These include shared living spaces, self-driving cars, off-grid eco-villages, habitable 3D printed homes, a plant-based bio-plastic toothbrush and even a hydroponic salad bar pop-up at the London Design Week.

“Space10 has popped in cities like London and Nairobi, but it is for the first time that we have opened a lab after Copenhagen, where we will have people working and will have projects. It is quite a milestone for us,” says Space10 co-founder Simon Casperson. He is from the Delhi studio, which will be operational till April 15 next year.

He shows a scalable prototype of an urban village which harnesses solar energy and blockchain technology, allowing houses to automatically share the energy created within the village. "The biggest reason to be in India is that it is where the future is. It has a young, tech-savvy, educated demographic. It's a hotbed for innovation and entrepreneurship. We research the big shifts happening in the world, like rapid urbanisation, lack of affordable housing, the climate crisis. It's going to impact all of us. Delhi is experiencing all of this and this the best place for us to anchor our research and design, much closer to real people. We are here to learn, gain new perspectives and find new people to collaborate with," says Casperson, days after Space10 hosting a session on design solutions for dealing with air pollution.

A typical manifestation of Space10's aesthetic can be found in the work done by the Delhi-based architecture firm Ant Studio.

Art, nature and technology are the propelling factors to design democratic solutions here. Founded in 2010 by Monish Siripurapu, a graduate from the School of Planning and Architecture (SPA), its trans-disciplinary projects are inspired by the teamwork and intelligence of ants.

His latest answer to the power-guzzling, energy-demanding, carbon-spewing ways of air-conditioning units is CoolAnt, which actually does look like a swarm of industrious ants breaking into a giant rock, poking holes bit by bit.

Siripurapu calls it the beehive.

The CoolAnt, AKA 'The Beehive', an eco-friendly alternative to the air-conditioner

The CoolAnt, AKA 'The Beehive', an eco-friendly alternative to the air-conditioner

It uses a gaggle of pipes, made of terracotta and burnished by artisans, that works as a cooling system using evaporative methods. He calls it "a throwback to vernacular architecture and traditional construction techniques” and goes on to explain the mechanism.

“It consists of hollow conical terracotta units stacked along the circumference of a cylinder which also encloses an air suction unit. Water is sprayed on the terracotta side of the system, wetting all the units. Air is sucked through these terracotta units, and in this process, water is evaporated from the surface of all units.”

The Beehive's first prototype will feature as an art exhibit at the upcoming Serendipity Arts festival in Goa. But, the eventual goal is to have a CoolAnt in every home. "We are trying to promote this through art installations. And they are real-time working models to check air pollution," says Siripurapu.

And how do you transform particulate matter into an art of darkness? Ask Anirudh Sharma, who sequesters air pollution and recycles it into ink. Always driven towards creating marvels which resolve social problems via engineering, Anirudh was too much of a self-starter to last in constraining academic curriculums of Indian technology training institutes. So he dropped out and earned a place in MIT's Media Lab back in 2012 after he designed shoes which could help the visually blind navigate cities.

Today Sharma is in MIT's Technology Review's 35 under 35 and Forbes' 30 under 30, thanks to AIR-INK, the first-ever commercial ink made completely from air pollution, usable for writing, printing and painting.

The ink we now use in our pen is produced by burning fossil fuels like coal or oil. Anirudh cleverly figured out a way to trap the requisite particles from the rampant pollutants in our air.

It is also in adoption pilots in finance, apparel and packaging companies. In a podcast on Spotify, Anirudh recalls those early experiments in tapping pollution from static sources and working with high voltage in a small flat in Bengaluru. Often, a wrong connection would set off fires and burn the prototype. But, things kept growing incrementally until he had the final product. And it was the art community which embraced his creation when the rest of the world raised their eyebrows.

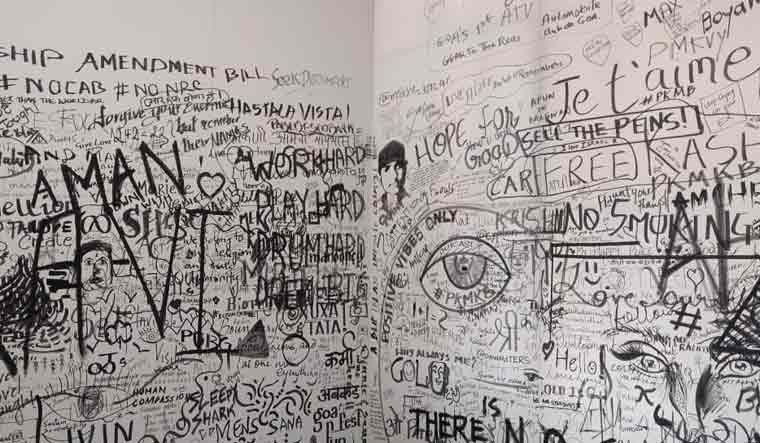

A wall tagged with the Air-Ink made from air pollution

A wall tagged with the Air-Ink made from air pollution

"Artists were the first people who adopted us. They would tell stories with their art to a wider set of people. We heard from artists that it's not just good ink...but it has a very sharp black colour," says Anirudh in the Kickstarter podcast, Just the Beginning.

"We call it the new black. This is because this black always changes. Every batch of black we make is never going to be the same because we are recycling pollution that comes from undefined sources.”