Twenty-five years ago, H.D. Deve Gowda reached the pinnacle of his political career when he took charge as India’s 12th prime minister on June 1, 1996. He was in power for barely a year, but the plain-speaking farmer leader from Karnataka had a lasting impact on the polished power corridors of Lutyens’ Delhi.

In his new book, Furrows in a Field: The Unexplored Life of H.D. Deve Gowda, author-journalist Sugata Srinivasaraju chronicles Gowda’s remarkable journey that made him one of India’s most improbable prime ministers. An excerpt from the chapter ‘Gowdanomics, Kisan Raj and Chidambaram’s debut’.

The very fact that Gowda had picked Chidambaram as his finance minister was an indication that he chose continuity over disruption. However, for a day, prime minister-elect Gowda was in a dilemma if he should pick Murasoli Maran as his finance minister or P. Chidambaram. He had mentioned this to his party colleague and later parliamentary affairs minister, Srikant Jena, but had quickly concluded that Chidambaram was a better fit. Maran, whom Gowda categorized as a ‘highly dignified gentleman’ was perhaps Gowda’s Plan B in case the Left parties opposed Chidambaram’s appointment.

Chidambaram himself had not expected to be named finance minister. He thought like Rao, Gowda would prefer an expert from outside. He recalled: ‘It was not the decision of the coalition partners or my party chief to make me finance minister, it was that of the prime minister. Even before he was sworn in, Gowda made it clear that I would be his finance minister. We were some eight or nine people making decisions. From my party, that is the Tamil Maanila Congress, it was Moopanar and myself. From other parties, there were Sharad Yadav, Lalu Yadav, A.B. Bardhan, Harkishan Singh Surjeet, A. Raja, C.M. Ibrahim, Murasoli Maran, T.R. Baalu and others. In their presence, he made it clear that he had decided to make me the finance minister. I had thought he would bring in an outside expert or an academic. When he mentioned my name, nobody opposed it. The other portfolios were still under discussion at that point. Under Gowda, people were nominated by parties, and portfolios were decided thereafter. In coalition set-ups after Gowda, this process was reversed, portfolios were distributed to parties and parties nominated ministers.’

That was Chidambaram’s debut stint as finance minister, and he was relatively young at fifty. Gowda had watched Chidambaram closely as a commerce minister under P.V. Narasimha Rao. He had also watched him resign during the Harshad Mehta securities scam because of his investments in a Bangalore firm that had come under investigation. From parliamentary exchanges, it is also apparent that Gowda had assessed Chidambaram to be closer in spirit to Manmohan Singh than to Rao. In December 1993, he had remarked sharply in the Parliament when discussing the securities scam: ‘Yesterday the whole argument of Chidambaramji was only to protect the finance minister and not the government. I could see that.’ All this was before Chidambaram quit the Congress in early 1996 to join the Tamil Maanila Congress under G.K. Moopanar, protesting Rao’s alliance with J. Jayalalithaa’s AIADMK in Tamil Nadu. ‘It was uppermost on my mind to signal continuity of policy to industry and investors. I knew the economic situation was not very bright, the oil pool deficit was rising, foreign debt was not looking good either. The World Bank and IMF conditionalities were also rather tight. I had observed all this as a chief minister. Therefore, when I had to pick my finance minister, I knew instinctively that it should be Chidambaram. I was aware his thinking differed from mine, but that was small compared to his ability to handle the situation,’ Gowda recalled.

Differences in worldview and approach cropped up early between Gowda and Chidambaram. When Chidambaram brought the draft of the budget for discussion, Gowda was not happy with the slant it had acquired. By then, the finance ministry had put queries and raised objections to some things Gowda had tried to do or had announced in public: ‘I was not very happy with the negative approach of the officials. I had not done anything that was not within my purview and powers. Therefore, I told Chidambaram in front of everybody that he should first understand that he was the finance minister of a thirteen-party coalition government and not a Congress finance minister. “Do not get me wrong, but what is the message that you are trying to give through this budget. How does our budget differ from the ones that Manmohan Singh has presented?” I asked. I also told him bluntly that he should have overhauled the finance ministry as soon as he took over because advisers and officers who worked with the previous regime would only perpetuate old ideas and old attitudes. Our government stood for something, and it had a common minimum programme too. I wanted the budget to reflect this and have a new imprint. I wanted it to signal hope to the poor and rural masses. I could see Chidambaram did not take my comments well. He was upset. When he and the officers were speaking, I used to shut my eyes but would be listening carefully. They thought I was drowsy. But when I said I cannot accept this budget, nor can I convince the coalition partners to accept it, they became alert.

‘Chidambaram left the meeting without saying anything. The next day he came in the morning and asked my private secretary how my mood was that morning? He was informed that I was sitting with Meenakshisundaram and disposing of files. After a while, the private secretary walked in and said the finance minister was waiting for the past fifteen minutes. I got angry with him, I asked why he hadn’t told me before. I got up and went myself to bring him in. “Why are you sitting here? You are one of the senior ministers, you should have just walked in.” I took his hand and led him into my room. We had a cordial exchange on all issues that I had raised the previous day. I handed over a document that I had kept typed and ready. I said I would like to see all this covered in the budget. He agreed to include them.’ To put it across through an economic platitude, Gowda had ensured that Bharat made space in India’s budget. That is rural India had found adequate representation.

—Excerpted with permission from Penguin Random House India

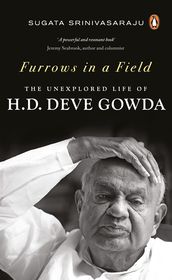

Furrows in a Field: The Unexplored Life of H.D. Deve Gowda

By Sugata Srinivasaraju

Published by: Penguin RandomHouse India

Pages: 562

Price: Rs799