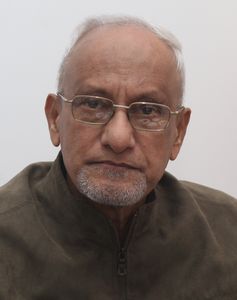

Interview/Major General (retd) Fazle Elahi Akbar, founder chairman, Foundation for Strategic and Development Studies, Dhaka

Major General (retd) Fazle Elahi Akbar has served as the defence and security adviser to former Bangladesh prime minister Khaleda Zia. He was instrumental in getting together major political stakeholders after Sheikh Hasina was flown out of Bangladesh to India on August 5, 2024.

Elahi says the army is watching the democratic transition, and that it is time to thrash out security concerns with India. Excerpts:

You were called by the army chief in those decisive hours during the student-led protests in 2024. Can you take us through that moment and what followed?

I was contacted sometime past midnight on August 5 and told that the chief of army staff wanted to see me the next morning. Those were extraordinarily tense days, and everyone understood the risks involved. My children are settled abroad, and my family was deeply concerned, but for me the decision was straightforward. I am a military man. When the army chief calls, you respond. I went to his residence at exactly 10am. He was already there, waiting. Even before sitting down, he made three things absolutely clear.

First, he said he did not want any further bloodshed. Second, he said he had no intention of holding onto power. Third, he said the crisis had to be resolved through a collective decision involving major political stakeholders. He believed the situation had reached a point where any delay would only lead to chaos and uncontrollable violence. He said he called me because he felt I was reasonably acceptable across political lines and within society, and that I could help reach out to key political leaders. He asked me to organise consultations as quickly as possible. I told him I would try my best. As we were concluding—around 10:25am—he informed me that the Indian Army chief would be calling him in five minutes. He invited me to stay, but I declined. I felt I should not overhear a conversation that could later be misinterpreted or compromise trust. I left immediately.

When did political leaders become involved in this process?

By around 1:00pm or 1:15pm, I received instructions to ask key political leaders to come to the army chief's office. I contacted the principal stakeholders, including BNP leaders, and asked them to assemble. It was during that meeting that the army chief formally announced that the prime minister had left the country. There had been no prior consultation with political parties about her departure.

How did political leaders react to that announcement?

There was a palpable sense of relief. People were exhausted. The immediate feeling was that the violence had stopped and that the crisis had ended without large-scale bloodshed. At that moment, nobody was focused on procedural or legal questions. Everyone was looking ahead—towards stability and what came next.

There has been a debate about whether allowing her to leave was the right decision. How do you see it?

This is a legitimate question. Many citizens felt she should have been taken into custody and brought to justice immediately, especially given the scale of repression over the years. That feeling is understandable. However, from a crisis-management perspective, allowing her to leave prevented massive bloodshed. Crowds were closing in from all directions. The military could not have resorted to indiscriminate firing. A national army cannot open fire on its own people. Had violence escalated at that point, the institution itself would have been irreparably damaged. In that sense, her exit helped stabilise the country.

How quickly was the decision made to fly her to India?

It happened very quickly. When you connect the dots—the phone calls, the aircraft movement, the absence of a transponder—it is clear this was not a purely unilateral Bangladeshi decision. Given India's long-standing relationship with her, I believe India was compelled to accept her. Otherwise, there was a real risk that she would be killed.

Does this now place responsibility on India regarding extradition?

Yes. The ball is clearly in India's court. Her alleged atrocities are not fabricated; they are documented, including by UN reports. If there is an extradition treaty, this should be treated as a legal and a moral matter, not one of political convenience.

You have said openly that you could not have spoken like this during her rule. Why was that?

Because fear dominated every layer of society. The media, judiciary, business community, security forces, and social elites—all were under intense pressure. You either complied, stayed silent, or faced consequences. Silence did not mean support; it meant survival. I am speaking today because that pressure has lifted. Fifteen years ago, even bribery would not have convinced me to speak this way—the cost to my family and my own safety would have been too high.

Looking back, how decisive was the role of the army during the July uprising?

It was decisive. Historically, no political movement in Bangladesh succeeds unless the army withdraws its support from the government. I have told political leaders repeatedly that rallies and agitation alone change nothing unless the army decides that “enough is enough”. What was unprecedented during the July uprising was the visible presence of the army on the streets after years of remaining in the background. Soldiers came face to face with civilians demanding legitimate rights. Soldiers come from the same society, the same families, the same communities. At that point, repression becomes impossible. When soldiers appear on the streets in such a context, collapse becomes inevitable. That is exactly what happened.

Historically, the Bangladesh army has had a complex role in politics and society. How do you see its place in the country's political future?

Historically, the army has had significant influence in our society. Despite grievances and criticisms, people still look to the army in moments of national crisis. There is a certain trust and emotional connection because the army is seen as a national institution, not a partisan one. At the same time, this creates a contradiction. Ideally, the army should be completely apolitical. But in reality, when political institutions collapse or lose legitimacy, society turns to the army as a stabilizing force. In this crisis as well, the army was reflecting what society wanted at that moment. Ironically, no elected government gave the army more benefits and privileges than the Hasina government. Over time, good officers were sidelined, and lesser-quality leadership rose through political allegiance rather than merit. Yet the army ultimately refused to suppress the people. This proves that patronage does not guarantee loyalty. Professionalism and meritocracy matter far more. The army must be left to its constitutional role, free from political manipulation. When dragged into politics, everyone ultimately loses.

How do you assess the performance of the interim government that followed?

The task before the interim government was enormous, and public expectations were even greater. They did manage to stabilise the economy to some extent, which was critical given the scale of financial damage—hundreds of billions siphoned out over the years. However, they struggled with law and order. This was largely because institutions like the police had been deeply politicised for years and conditioned to follow unlawful orders. Reforming that overnight was simply not possible.

Was another military intervention a possibility if elections were delayed?

I do not believe the situation reached that point. There was convergence among all major stakeholders—the interim government, the army chief, and political parties—that elections were necessary. Soldiers cannot remain deployed indefinitely. Elections became the only viable exit.

What should be the top priority for the next elected government?

Governance, not merely winning elections. Depoliticisation must extend to all institutions, especially the judiciary. A politicised and corrupt judiciary leaves citizens insecure and strips the constitution of its meaning. Judicial independence is fundamental. Without it, rights exist only on paper. The interim government has made some progress, but this is a long-term struggle. This is another historic opportunity. Bangladesh has missed many before. The younger generation is impatient and determined to see real change. If elected leaders fail again, history suggests there will be another uprising—and the army will once again side with the people.

Also Read

- ‘We are committed to pluralism, inclusive governance’: Dr Shafiqur Rahman

- My biggest concern is near absence of women in Bangladesh's political process

- ‘Coalition with Jamaat won’t lead to a theocratic state’: Nahid Islam

- ‘Aspirations of 2024 nowhere to be seen’: Mahfuz Alam

- ‘Muhammad Yunus was picked by Biden state department’: Sajeeb Wazed Joy

- ‘De-securitising foreign policy is extremely important’: Amir Khasru Mahmud Chowdhury

Some security concerns continue to shape public perceptions of India in Bangladesh. How do these affect the relationship?

Public trust is heavily influenced by issues such as border killings and the Rohingya crisis. Border deaths, in particular, generate deep resentment and quickly undermine goodwill, regardless of high-level diplomatic ties. Managing borders is a law-enforcement challenge, not a military one, and modern technology can prevent crossings without loss of life. Reducing border killings to zero would significantly improve public perception in Bangladesh. The Rohingya crisis places an unsustainable humanitarian burden on Bangladesh. India has strategic influence in Myanmar which could be used to proactively push for repatriation of Rohingyas under international guarantees. A stable resolution would benefit not just Bangladesh but India's own security and connectivity interests in the Northeast.

How would you define Bangladesh's strategic posture going forward?

Let me say this very clearly: Bangladesh has no territorial ambition. We are fully content within our internationally recognised borders. We do not seek to redraw maps, or project power beyond our territory. Bangladesh looks inward towards development, democracy and dignity. What we want is peaceful coexistence, mutual respect, and security cooperation. When rhetoric—especially irresponsible commentary on social media—questions Bangladesh's territorial integrity, it poisons public perception.