Jessel Taank, actor and entrepreneur

Pochampally, Telangana

AMONG THE MOST popular American reality TV shows is The Real Housewives of New York City, and the first Indian-American on it is entrepreneur and publicist Jessel Taank. Born in the UK but living in the US currently, Taank also has an e-commerce platform that promotes South Asian designers in America. Among these is Jade By Monica and Karishma, a 15-year-old label that has moved from a fashion boutique to a tour de force in recent years. Much of this is thanks to the gorgeous embroidery house—the world-renowned Chanakya International—that the family of the founders, who are sisters-in-law, is known for. It had co-hosted a mega Dior fashion show at Mumbai’s iconic Gateway of India last year.

But this piece is about ikat weaving. Ikat is a part of Jade’s Grassroots Artisans Project that works in villages such as Pochampally, Bholpur, Salem, Bhuj, Palanpur and Barmer, creating fabulous fashion using ikat, soof, bandhani, and even batik.

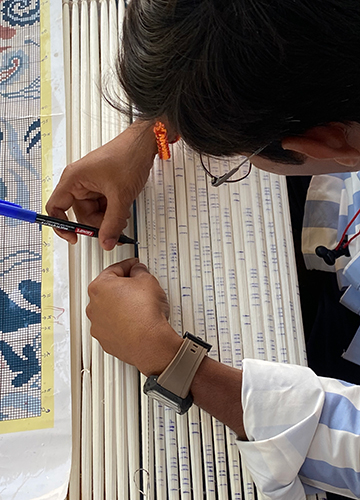

This isn’t my first visit to Pochampally in Telangana because ikat is just marvellous. It is arguably the only craft where the yarn is dyed first and then woven into the fabric. The patterns are pre-decided on a graphic blueprint, so the precision required is mathematical. Ikat means ‘to tie’, and the technique comprises knots made on a yarn, or thread, to resist the dye. In bandhani, another craft that uses knots to resist dye, the knots are made on a ready piece of cloth.

In Pochampally, two hours from Hyderabad, we meet Ennam Shiva Kumar, 50, who runs a producer group, or a rural collective, called Shreeranjan Weaves. Shivaji is more of a businessman than a weaver; he says he spent a decade growing paddy before returning to his weaving roots.

The entrance to his massive unit—comprising two to three large sheds—shows off standees featuring him with President Droupadi Murmu, who had visited his workshop last December. His monthly income is Rs2 lakh, and he says his expenses at the workshop are the same. He employs around 100 artisans in the facility.

His wife, Madhavi, and two children Rikshit, 23, and Himabindu, 20, both English speakers, are around assisting him especially with translation. Rikshit has finished his B.Tech in textile technology from Bengaluru and is preparing to do an MBA. Himabindu is studying fashion technology, and says both she and her brother want to run their father’s business.

Pochampally ikat is similar to the revered Patan Patola, as it is a complex double ikat (Odisha’s Sambalpur, on the other hand, makes a simpler single ikat), but is nowhere as expensive. A Patola sari from Surat can cost Rs50,000 or more, but a Pochampally ikat starts at Rs9,000.

Shivaji opens a floral silk cloth, designed by Jade’s design team. The textile is unlike an ikat pattern, and only on close inspection can one see the zigzag borders on the motifs. It won Shivaji a state award for being so unusual and elaborate. “Usually ikat graphics are 80 boxes, yours were 285,” he tells Monica Shah, half-complaining, half-proud.

Shah is thrilled that Shivaji is open to experiment, and has a dogged determination to conquer complex patterns. She has been working with him for more than a year now. She loves the three-piece pant suit for Taank, and says she preferred to use a four-ply thread over a two-ply thread in spun silk, so it structures beautifully for evening wear.

One of Shivaji’s sheds is a massive silk unit. He buys silk worms from the Hyderabad cocoon market for Rs500-Rs700 per kilo. He then boils and cools them to create the fibre. There are large basins with fancy plumbing for hot water on one end, and small cooling vats attached to a mechanised spindle machine to remove the fibre and make the silk. The silk is then whittled into a bobbin before it is ready to be woven. One silkworm cocoon can give you 1.25km of silk. The empty shell of the silkworms is flattened and turned into textile, too, before it is shipped to cool Delhi to make razais (stuffed blankets). Some of these have pieces of the brown worm woven into them.

Also Read

- Farm to fashion

- Bargachia and Bandpur, Bengal | How Rahul Mishra nailed the pre-stitched sari for Zendaya

- Gondal and Adesar, Gujarat | Himanshu Shani and 11.11: Pioneering India's artisanal fashion

- Malihabad, Uttar Pradesh | Anjul Bhandari is on a mission to empower chikan artisans

- Semra, Uttar Pradesh | Raw Mango's handloom revolution: Blending tradition and modernity

The next shed is where the weaving takes place. Shivaji has nearly 30 looms here, as well as various other large machines for warping and spinning into bobbins. Only women weave here, and Shivaji says he has met all their husbands. The women all wear vivid cotton ikat saris and a jasmine string in their hair, to keep them perfumed in the severe heat and humidity.

South India and northeast India are full of women who weave. In north India, where most of the large-scale weaving takes place, the weavers are all male.