According to recorded history, clothing in India has been hand-spun, dyed and handwoven right up to the Indus Valley Civilisation, over 3,000 years before Christ. The Greek historian Herodotus described Indian cotton as “a wool exceeding in beauty and goodness”. Trade routes by land and by sea created a great cultural exchange between India, China, Central Asia and Europe. In the early 17th century the East India Company began taking India’s local produce, primarily raw cotton, and industrialise it into cloth that it sold to the rest of the world, including India. At the time, Indian cotton dressed 90 per cent of the world.

Mahatma Gandhi took us back to our ancient roots of spinning, weaving and dyeing our own cloth instead of buying back from the British what they stole from us. Gandhi famously said, “If the village perishes, India perishes.”

Today, India’s fashion industry is growing and thriving thanks to rural enterprise. The story of Indian fashion is the story of our village crafts. India is on its way to dressing the world once again. And here are five examples of international outfits whose roots can be traced to the villages where they were made.

Zendaya, actor

Bargachia and Bandpur, Bengal

ALL EYES WERE on American movie star Zendaya when she came to India in April 2023 for the launch of the ‘India in Fashion’ exhibition that inaugurated the Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre (NMACC) in Mumbai. Designed by Rahul Mishra and custom-made for the actor, the blue sari she wore featured three-dimensional embroidery. It was then tailored to look like a skirt with a trail and a veil over one shoulder, almost like a gown with a long scarf. It became one of the most modern and easy to wear iterations of the sari. The embroidery featured stars in a dark sky, and the hem had beautiful fauna—tigers, squirrels, flamingos—looking up at the sky.

Mishra says this was the design for the sari he had in mind when Zendaya’s stylist Law Roach approached him. Mishra had previously designed for Zendaya for a Bulgari event in 2020. “Law called and said Zendaya and he were coming to Mumbai and needed clothes for the NMACC opening,” says Mishra. “I wanted to make something Indian. I had never done a pre-stitched sari before, but I thought she may like it. I also made two evening gowns which she loved and took back with her.” But she wore the sari, which Mishra had hoped she would pick and celebrate India internationally. “The pre-pleated sari can be worn by anyone,” he says. “Many Chinese celebrities bought some from us, too. In fact, almost 60 per cent of its customers were not Indian. So, it can work like an evening dress.”

Mishra is famously an advocate of reverse migration, where he encourages artisans who live in cities to move back to the villages and work from there. He has previously told me that he pays his artisans a city salary, but once they live and work in the village, its ecosystem thrives. Money is made in the village and spent in the village, and that’s how the village grows.

Mishra met Afzal Saidullah Mullah when they were both working for an embroidery house in Mumbai in 2008. By 2013, they had quit and become partners.

Afzalbhai now manages three workshops in Bengal’s Howrah district, two in the village Bandpur, and one in Bargachia, a village 20 minutes away.

When I land at the Kolkata airport, Afzalbhai receives me and takes me directly to the villages. He is accompanied by Sabeena, a 31-year-old widow with two children, who lives in a mud house by the creek. She doubles as Afzalbhai’s housekeeper, and is not permitted to work in his workshop as “families here don’t allow women to work outside the house”.

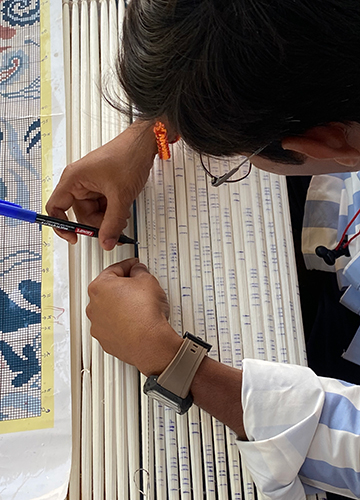

We climb up a dusty office building to Afzalbhai’s atelier in Bargachia. There are around 70 men here, bent over several large frames with fabric stretched across it. Heads down, they silently and serenely move their embroidery needles about as though with muscle memory. It’s almost like swimming underwater, soundlessly and with studied movements.

“Can’t you play some music?” I ask Afzalbhai. “They are listening to their own choice of music through their earphones,” he smiles. The men are warm and welcoming, and want to take pictures with me. Their workmanship is the opposite of their workplace—it’s so fine, fanciful and extraordinary that it is almost impossible to believe the embroidery is made by hand.

“I didn’t know who the sari was for,” Afzalbhai says when I show him Zendaya’s picture on my phone. “I don’t know who she is.” But he recalls eight men had worked on the sari. “Normally a sari takes between 400 to 2,000 hours to create, depending on the volume of embroidery,” he says.

Bargachia is known for its creative labour, as Afzalbhai calls it. No one here is interested in academics. In the atelier, different artisans specialise in different embroidery techniques, like aari (a hooked needle) or zardozi (a raised style of gold thread-work). Madhav, an artisan, shows me the different types of needles for different techniques.

The monthly rent for the larger unit in Bargachia is Rs23,000, while it is Rs8,000 and Rs3,000 respectively for the smaller units in Bandpur. The workers get paid between Rs800 and Rs1,000 a day. Mishra sends the fabric and one embroidered swatch or panel, and the artisans emulate the embroidery flawlessly.

“Even though I was working at the embroidery house where I met Rahul for 17 years, I left when he left. He has a good heart. His colours and design process are so unique,” says Afzalbhai. “The salary is also good, and I always get paid on time.”

In 2023, Mishra took Afzalbhai and Prince, another embroidery artisan from the Noida atelier, to the Paris Haute Couture Week. It was Afzalbhai’s first time abroad, even though he has a daughter who studies in Newcastle, UK (the other two children are teachers in Mumbai). “Paris was just too beautiful. Rahul made us a part of the show,” he says.

Afzalbhai is clearly a benevolent leader to his artisans. “I am an embroiderer too, so I know how difficult the work is. I don’t believe in pushing people; some are strong and quick, others are slower. But I ensure I keep everyone employed,” he says. “Plus, there is a lot of pressure on the eyes.”

The remarkable thing about the villages is that half the artisans are Hindu and half Muslim, and everyone gets along fine. “We really struggled during Covid,” says Afzalbhai. “Rahul helped us for sure, but our Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee ensured no one was hungry.”

Zohran Mamdani, candidate for mayor, New York City

Gondal and Adesar, Gujarat

PERHAPS ZOHRAN MAMDANI’S love for Indian fashion comes from his mother, the acclaimed filmmaker Mira Nair, known to flaunt textile-first designer labels such as 11.11 and Raw Mango.

“Oh, but his shopping skills are nothing like his mother’s,” says Himanshu Shani, the designer and founder of one of India’s finest fashion labels, 11.11, known to work with rural artisans and create fine artisanal contemporary wear. “Mira will buy many things within minutes, she knows exactly what she likes and is quick at making up her mind. Zohran will take his time. He will try on an item multiple times before putting his money down.” One could say it is the joy of helming a small niche label, but Shani is friends with many of his clients like Nair and Mamdani.

Another customer and friend is the billionaire co-founder of Zerodha, Nikhil Kamath, part of the Forbes ‘India’s 100 Richest’ list of 2024. Kamath also has an independent podcast and has interviewed Prime Minister Narendra Modi and actor Ranbir Kapoor—two men who rarely speak to the press. He often wears clothes from 11.11 on his podcast. Rumour has it that a beautiful white tangaliya shirt he wore for his interview with the prime minister led to a Padma Shri for a tangaliya weaver this year. Kamath has also expressed interest in investing in 11.11.

Shani says that Mamdani, who got married recently, has worn an indigo jacket from 11.11 several times in public already. Especially during March and April, while canvassing for the state assembly election in New York.

“Kala cotton is a fibre that is intrinsic to Kutch. It is a short-staple yarn, which means it is a little coarser, but it is fully organic. The only water used to grow it is natural rainwater. It requires no irrigation, and is fully pesticide free,” Shani says. His label, 11.11—in which American designer Mia Morikawa is a partner—is known for making handspun, handwoven denim and other contemporary wear from kala cotton of Kutch, Gujarat. Shani shows me around Gujarat, where kala cotton is farmed and woven. The dyeing for Mamdani’s jacket was done at the 11.11 atelier in Delhi, where Shani is developing modern ways to make natural and long-lasting indigo, a plant-based blue dye also indigenous to India. The plant and the colour got their name from the country.

Our first stop is Gondal, a small town in Rajkot district, formerly a princely state but still full of beautiful monuments and finds mention in Abul Fazal’s book Ain-i-Akbari.

The fabric for Mamdani’s jacket was sourced from Udyog Bharti, a khadi emporium in the heart of Gondal founded in 1957 by the visionary Hargovindbhai Patel to employ and empower weavers. “You will find the finest khadi in India, and possibly the world, here,” says Shani. The Indian government’s Khadi and Village Industries Commission mandates that only handspun and handwoven fabric can be called ‘khadi’ and each khadi manufacturer needs a certificate from it.

We are here to meet Kavin Patel, the grandson of Hargovindbhai. “My grandfather had refined the charkha. It is not a metal device but with 8-10 spindles. The yield and the earnings increase. However, it is fully mechanical and free of electric dependence,” Kavin tells me. Udyog Bharti now employs 120 weavers and creates 2.5 lakh metres of handspun handwoven fabric. Shani says it is the largest producer in the country. Handspun and handwoven denim is also fully biodegradable, he says.

We visit Jagdishbhai at his home in Hamapur, a small village 70km from Gondal. He is a generational weaver, and is currently on his loom weaving indigo-dyed denim. He is building a pucca extension to his house. His two daughters are married, and one son goes to a nursing college.

Hamapur once had more than 50 weavers, but now has only around six or eight. Most of the younger generation has gone to the diamond polishing factories.

Denim is tougher to weave than cotton; I try my hand at it on Jagdishbhai’s 50-year-old loom. Each weft takes two or three beats, whereas silk or cotton takes just one beat. Kavin informs me the weavers here make Rs100 per metre and weave six to eight metres a day. They also get a 20 per cent annual bonus, and the government gives them 22 per cent of their earnings via direct benefit transfers every quarter. There is an additional Rs8 per metre given by the government, but that is not fully implemented yet.

Hamapur comes under the Gir National Park’s area and sometimes one can spot an Asiatic lion in the village. The weavers here think Shani is a tailor and makes all the clothes by himself.

The next day, Shani takes me to Adesar in Kutch, five hours by road from Gondal. We visit a 330-strong farmers’ collective, Adesar Vistar Khet Utpadan Co Ltd, and even a kala cotton farm. The producer group’s head Devshi Parmar tells me that kala cotton has few takers and barely any orders. They prefer to grow castor as there is demand for castor oil from the US, Europe and Australia.

We carry back cotton buds and twigs as keepsakes.

Devika Bulchandani, CEO of Ogilvy & Mather

Malihabad, Uttar Pradesh

WHEN OGLIVY’S GLOBAL CEO Devika Bulchandani met designer and chikan specialist Anjul Bhandari in Delhi, her only brief to Bhandari was she wanted something she could wear anywhere in the world. Bhandari then suggested a coat in chikan that was luxurious as well as versatile.

“Black is clearly not my colour, I prefer pastels. But Devika wanted something western, so we customised for her. I’ve used coloured threads that stand out instead,” Bhandari tells me as we drive from the Lucknow airport to Malihabad, nearly two hours away.

We are meeting sisters Shanno, 50, and Shahana Parveen, 35. They are the daughters of Abdullahbhai, a master embroiderer renowned across Lucknow. Chikan embroidery enjoys a Geographical Indication (GI) tag in and around 100km of Lucknow. It traditionally consists of white thread work done on white muslin, but its popularity has seen many derivatives in coloured thread and assorted fabrics. Fine chikan comprises 32 known styles of embroidery, with old names like murri (from Kakori region), bijli, kauri, bakhiya, pechni, jaali, phanda, keel and the like.

“All my learning in chikan or kamdani (metallic embroidery, also known as mukaish) is courtesy Abdullahbhai. I don’t have a store or take part in fashion weeks; my only mission is to keep the income of my artisans going,” Bhandari says. “Even if they give me only 90 working days in a year, I am fine. I have much to learn from them about work-life balance.”

Shanno has just recovered from a kidney ailment and is still weak. Shahana had no interest in embroidery, but had to take over the atelier, where more than 100 girls work. The atelier is also their residence, partly funded by the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana housing scheme. Since it is Ramzan, the holy month of fasting for Muslims, only the Hindu women have come to work. They wear alta on their feet as they celebrate Holi for one month in UP, even though the festival of colours is a one-day affair. “Lucknow is the only place in UP which has not seen Hindu-Muslim riots yet, and I hope it remains like this,” Bhandari says.

The girls are embroidering on a white georgette fabric with indigo block-printing done by a master printer called Munnabhai. After the intricate embroidery is done, the large spaces will be filled with jaali work, an airy grid borrowed from Mughal architecture. Then the fabric is washed, starched with charak (rice water) and dyed (the white cotton embroidery threads do not catch the dye, they remain white). Finally, after the embroidery, the work is embellished with mukaish, or then glass beads that Bhandari imports from Japan. Then it is stitched to make a sari or an outfit. “It takes me one year to get a sari ready. If it is ek-taar (embroidered with a single strand as opposed to a two-strand thread), it takes two years,” she says.

The Parveen sisters who manage the atelier receive 20 per cent of the fee for the final product, so they can make between Rs1.5 lakh and Rs2 lakh per month. The other women workers make around Rs15,000 per month. “All our husbands work and run the house. We use our money for ourselves, buying fancy clothes and such,” Rekha, an artisan, tells me.

Our next stop is Munnabhai’s home in the old city of Lucknow. His real name is Mohammed Wasif, but no one knows him by it. Munnabhai, 55, is married to a much younger woman who he serenades every few hours when he isn't up at the nearby mosque calling the azaan. He is a master storyteller and claims to have called the azaan in Saudi Arabia and Dubai, too. Munnabhai learned the craft from his maternal grandfather, and has hand-carved blocks that are 150 years old. Some are so slim, no one can replicate them any more. “Block-printing is the secret code between a printer and an embroiderer,” he says. “A printer has to know which embroidery pattern works where, and we lead the embroiderers without even meeting them.”

I also visit the beadwork and zardozi embroidery unit in old Lucknow. Shanu Mirza (name changed to protect privacy) says this is the area from where actor and singer Begum Akhtar hails. His sons continue to work in the atelier here (one of them was the Dubai Sheikh’s private embroiderer but has moved back). Mirza tells me locally sourced plastic beads cost Rs20 per kilo, but Bhandari’s glass beads are at Rs14,000 per kilo.

Our final stop is the kamdani workshop of the two brothers of the Parveen sisters, Shahnavaz and Parvez. Mukaish is a metallic thread embroidered into a circle by hand, then rolled over for smoothness with a seashell. It has also been passed through a mechanical rolling machine. A mukaish sari can take five years to make. Shahnavaz shows me how the circle is embroidered, just within a minute thanks to his expertise, and he even cuts the metal with his bare hands. It’s magic, I tell him. “But very hard to do, so no takers,” he replies.

Anita Chhiba, founder of the media platform Diet Paratha

Semra, Uttar Pradesh

IT WAS DURING the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 that master weaver Mohammed Naseem Khan’s (name changed to protect privacy) family moved from Azamgarh to Varanasi, or Benares. “We were a family of cotton weavers, but the British had banned cotton weaving. Benares is known for weaving in silk, so we came here,” says Khan, 64.

Khan now has his own weaving centre, an expansive three-storey residential and weaving space, in Semra, one hour from Varanasi, where nearly 150 weavers work. The Benaresi sari is among India’s most glamorous saris, thanks to the buttery silk and gold threads woven all over it.

More than 80 per cent of Khan’s commissions come from Raw Mango, the extraordinary Benaresi-special label helmed by designer Sanjay Garg. As we meet, one of Garg’s textile design assistants, Manya Agarwal, is also accompanying him. She is carrying an extraordinary sari with her, a chessboard of black and gold checks, but the pallu turns into a stretchy lycra. The sari, part of Garg’s experimental ‘Children of the Night’ collection of 2024, was shown at a fashion week last August to celebrate 15 years of the Raw Mango label.

But before this, the sari made its debut when Diet Paratha’s Anita Chhiba wore it at London’s British Fashion Awards in December 2023. Chhiba is a London-based New Zealander who launched her Instagram handle Diet Paratha to chronicle and promote South Asian culture globally.

“Sanjay started weaving Benaresis with me,” says Khan. “I used to work at the Weavers’ Service Centre in Varanasi. There are 28 such centres across India set up by the ministry of textiles. Sanjay met me here. In 2018, I started my own studio in this space. In 2020, I retired from the government job.”

Khan recognises the sari immediately and brings over another weaver, Mushtaq Mohammed, 60, who actually wove it. “I like learning new things. I had practised weaving this sari seven to eight times, and through trial and error I made the final product,” he tells me.

The sari is plain silk and zari, with lycra introduced in the pallu to make for elastic strips. It has a one-warp, two-weft (one black and the other gold zari) weave. The sari is thus reversible, a black check on one side is a gold check on the other. Khan explains this is called ‘backed cloth’ in textile language.

Garg has been experimenting with the Benaresi handloom since 2020. He was determined to introduce knitwear into handloom, the Benaresi weave, as the whole world wears knitwear. He wanted to create a “handloom knit” product, a technical first, that could dress the world. This sari was his attempt at handloom mimicking knit. Agarwal tells me Raw Mango made only 20 pieces of this sari, and some in a white and blue variation as well.

“We wanted to make pieces that appear to dance with the ebb and flow of elasticity, like flickers of light,” Garg tells me. “One of the ideas was what a ‘handloom knit’ could look like; this questioning underpinned our process. We were able to create this technically through the introduction of lycra on the handloom, and the use of gota, a typical surface ornamentation. Alternating between silk and lycra, we were able to create an elastic palla, treating it as a fluid blouse. The gota made the textile heavier, allowing us to experiment with draping. We wanted to push the limitations of the handloom, responding to contemporary demands.”

Khan is thrilled with this sari. “Benaresis are very popular and the business of the silk-gold sari is thriving,” he says. “But we also need to focus on the younger generation, as they ensure longevity for a textile tradition. We need to keep offering them new things, as this ensures continued work for us for generations.”

Even as he shows me around, Khan says he is keen that more women get involved in Benaresi sari weaving. “All the pre-loom activities—the winding and warping of thread—are done by the women. Usually they don’t get paid for this service, as they only help the husbands in their work. But we ensure the women get paid for pre-loom work, too,” he says. He shows me the residential chambers of the centre—large rooms with a bed, sofa, cupboards and curtains like a regular home. The women’s spinning and pre-loom equipment lies around, even as their children study for exams.

Jessel Taank, actor and entrepreneur

Pochampally, Telangana

AMONG THE MOST popular American reality TV shows is The Real Housewives of New York City, and the first Indian-American on it is entrepreneur and publicist Jessel Taank. Born in the UK but living in the US currently, Taank also has an e-commerce platform that promotes South Asian designers in America. Among these is Jade By Monica and Karishma, a 15-year-old label that has moved from a fashion boutique to a tour de force in recent years. Much of this is thanks to the gorgeous embroidery house—the world-renowned Chanakya International—that the family of the founders, who are sisters-in-law, is known for. It had co-hosted a mega Dior fashion show at Mumbai’s iconic Gateway of India last year.

But this piece is about ikat weaving. Ikat is a part of Jade’s Grassroots Artisans Project that works in villages such as Pochampally, Bholpur, Salem, Bhuj, Palanpur and Barmer, creating fabulous fashion using ikat, soof, bandhani, and even batik.

This isn’t my first visit to Pochampally in Telangana because ikat is just marvellous. It is arguably the only craft where the yarn is dyed first and then woven into the fabric. The patterns are pre-decided on a graphic blueprint, so the precision required is mathematical. Ikat means ‘to tie’, and the technique comprises knots made on a yarn, or thread, to resist the dye. In bandhani, another craft that uses knots to resist dye, the knots are made on a ready piece of cloth.

In Pochampally, two hours from Hyderabad, we meet Ennam Shiva Kumar, 50, who runs a producer group, or a rural collective, called Shreeranjan Weaves. Shivaji is more of a businessman than a weaver; he says he spent a decade growing paddy before returning to his weaving roots.

The entrance to his massive unit—comprising two to three large sheds—shows off standees featuring him with President Droupadi Murmu, who had visited his workshop last December. His monthly income is Rs2 lakh, and he says his expenses at the workshop are the same. He employs around 100 artisans in the facility.

His wife, Madhavi, and two children Rikshit, 23, and Himabindu, 20, both English speakers, are around assisting him especially with translation. Rikshit has finished his B.Tech in textile technology from Bengaluru and is preparing to do an MBA. Himabindu is studying fashion technology, and says both she and her brother want to run their father’s business.

Pochampally ikat is similar to the revered Patan Patola, as it is a complex double ikat (Odisha’s Sambalpur, on the other hand, makes a simpler single ikat), but is nowhere as expensive. A Patola sari from Surat can cost Rs50,000 or more, but a Pochampally ikat starts at Rs9,000.

Shivaji opens a floral silk cloth, designed by Jade’s design team. The textile is unlike an ikat pattern, and only on close inspection can one see the zigzag borders on the motifs. It won Shivaji a state award for being so unusual and elaborate. “Usually ikat graphics are 80 boxes, yours were 285,” he tells Monica Shah, half-complaining, half-proud.

Shah is thrilled that Shivaji is open to experiment, and has a dogged determination to conquer complex patterns. She has been working with him for more than a year now. She loves the three-piece pant suit for Taank, and says she preferred to use a four-ply thread over a two-ply thread in spun silk, so it structures beautifully for evening wear.

One of Shivaji’s sheds is a massive silk unit. He buys silk worms from the Hyderabad cocoon market for Rs500-Rs700 per kilo. He then boils and cools them to create the fibre. There are large basins with fancy plumbing for hot water on one end, and small cooling vats attached to a mechanised spindle machine to remove the fibre and make the silk. The silk is then whittled into a bobbin before it is ready to be woven. One silkworm cocoon can give you 1.25km of silk. The empty shell of the silkworms is flattened and turned into textile, too, before it is shipped to cool Delhi to make razais (stuffed blankets). Some of these have pieces of the brown worm woven into them.

The next shed is where the weaving takes place. Shivaji has nearly 30 looms here, as well as various other large machines for warping and spinning into bobbins. Only women weave here, and Shivaji says he has met all their husbands. The women all wear vivid cotton ikat saris and a jasmine string in their hair, to keep them perfumed in the severe heat and humidity.

South India and northeast India are full of women who weave. In north India, where most of the large-scale weaving takes place, the weavers are all male.