During Losar, the Tibetan New Year, Gyayum Chenmo—literally “Great Mother”—the mother of the 14th Dalai Lama, allowed only one new item of clothing to be worn. It was her way of reminding her children and grandchildren that they were refugees, and that many Tibetan families could afford far less. From the fields of Amdo in eastern Tibet to the palaces of Norbulingka—the summer residence of the Dalai Lama in Lhasa—and later into exile in Dharamsala, she remained the guiding force of the Dalai Lama and the spiritual anchor of her family. As the matriarch of seven children and several grandchildren, she taught them discipline, compassion and mindfulness.

Once, her grandson Khedroob Thondup was feeding live worms to his aquarium fish. She stopped him gently. “This is not right,” she said. “You are letting one living being eat another.” From that day, he fed them only dry food.

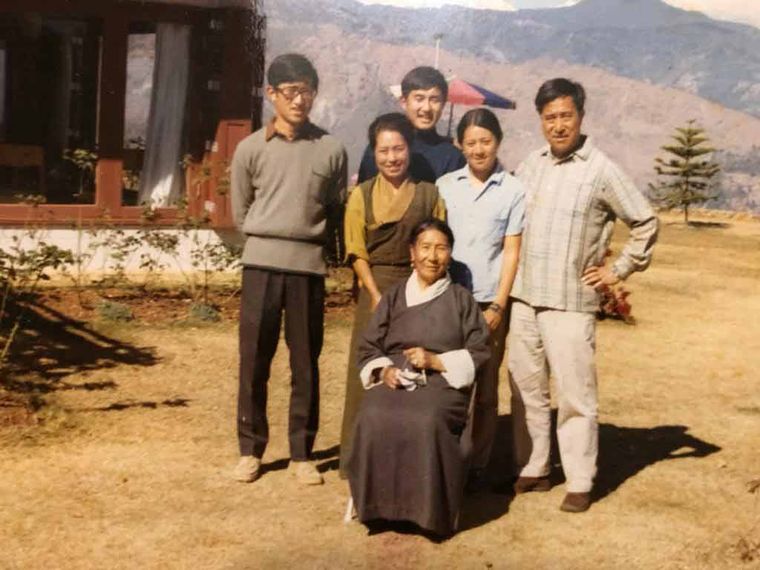

Affectionately called “Mola” or “Momo” (Tibetan for grandmother, with “la” as an honorific), she passed on her love for India to her grandchildren. “My grandmother would join us on picnics, walk in gardens, and enjoy Indian street snacks with great enthusiasm,” says Khedroob, now 73. “She also loved cinema, and never lost her sense of wonder. She particularly liked stories of moral strength and human kindness.” She died in 1980, leaving behind not just her family but an entire nation in exile that continues to draw from her emotional and spiritual legacy. To them, she remains Gyayum Chenmo—the Great Mother.

Two women have quietly shaped the course of modern Tibetan history: Gyayum Chenmo and Jetsun Pema, the Dalai Lama’s youngest sister. One shaped the Dalai Lama himself; the other shaped the generations that followed. Jetsun Pema, who turns 85 on July 7, carries the legacy forward—offering education, stability and identity to thousands of Tibetan refugee children. Known today as Amala—Mother—she is a maternal figure to a generation raised far from home. Together, these two women form the unshakeable foundation of the Tibetan exile story.

That story begins with the birth of Gyayum Chenmo into a peasant family in Amdo in the year of the Iron Ox. (In Chinese zodiac, each year is associated with one of the five elements and is represented by an animal.) She was named Sonam Tsomo and grew up preparing food, hosting travelling monks, and making offerings with joy and reverence. One of her fondest memories, shared with Khedroob, was helping her mother prepare thukpa, the noodle soup for which Amdo is famous. She loved pounding garlic and chillies late into the night, often earning scoldings from her grandfather for smelling too much of garlic. But she was strong-willed and never stopped. “Her mother was an exceptional seamstress,” says Khedroob. “As a girl, my grandmother learned to sew, cook and manage a household—skills she later passed on to her own children and to us.”

She married in 1917 into another peasant family in the remote village of Takster, a nine-hour horse ride from her home. Her wedding, as was the custom, was timed astrologically, and her mother spent three years preparing a trousseau: 35 pairs of shoes and 32 sets of handmade clothing. Though not formally educated in scriptures, Sonam was deeply rooted in her traditions. After marriage, she was known as Diki Tsering—“Ocean of Luck”. Of her sixteen children, seven survived. Among them was a son born in 1935 who would be chosen as the 14th Dalai Lama.

“She once told me she had a vivid dream before her son’s birth,” recalls Khedroob. “She didn’t know what it meant, but sensed something extraordinary.”

When the search party arrived in Taktser, she did not know they were looking for the 14th Dalai Lama. But when they found her son, everything changed. They confirmed his identity and quietly prepared for a secret journey to Lhasa.

Life in Lhasa was not easy. She had left the familiar field of Amdo for the Tibetan capital’s highly stratified society. “Her husband—my grandfather—was a simple man with a strong temper, and the Lhasa aristocracy did not take kindly to him,” says Khedroob. After the Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1959, she was among the first to flee Norbulingka on March 19, disguised as a man, with the Dalai Lama dressed as a soldier. She wore her son-in-law’s old coat, smeared mud on her boots, and carried a toy rifle. “When a plane flew overhead near Tsonadzong, they threw themselves to the ground, fearing an attack. Later, they learnt that the plane was sent by the Indian government to locate them,” he says.

At Chidisho, she shed her disguise and they slept in a loft above pigs. Whenever she had the chance, she always baked bread for the next day’s journey. “Most of us have grown up with a special fondness for bread,” says Khedroob, recalling the memory of eating loaves of freshly baked bread.

Khedroob’s father, Gyalo Thondup—the Dalai Lama’s eldest brother—was instrumental in building connections with the Tibetan government in exile and the Indian government. “My father had already been in touch with the Khampa soldiers (Tibetan warriors from the Kham region) and the Indian authorities to prepare for their arrival,” says Khedroob. When they crossed into India, they were met by Indian officials, whom she later described as “kind and welcoming.” After getting big receptions at Tawang, Bomdila and Siliguri, they spent a year in Mussoorie. She later joined the rest of her family in Darjeeling, home to the Thondups, before eventually settling in Dharamsala.

Exile was harsh, but she adapted with resilience. “Tibetan women like Amala played a central role in shaping our future,” says Jetsun Pema. “After our father died when I was young, our mother was the one who brought us up with her strong, practical, emotionally grounded ways. She understood the importance of education.”

Jetsun, the only child born in the Norbulingka compound after the Dalai Lama’s recognition, was born in the family’s pantry—the only secluded part of the house. Her birth was witnessed only by her elder sister Tsering Dolma.

“A few days after my birth, my mother went to see His Holiness and, as is Tibetan Buddhist tradition, requested him to give me a name. Without a moment’s hesitation, the Dalai Lama, even though he was only five years old then, named me Jetsun Pema—Virtuous Lotus,” she says. It was the first time that the 14th Dalai Lama had given a name. Jetsun is also part of his very long formal name: Jetsun Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshi Tenzin Gyatso.

“The fact that he is my older brother is a karmic connection,” says Jetsun Pema. “Just like for any other devotee, His Holiness is my spiritual master and leader. His words of wisdom have guided me from the beginning, prioritising my own role in our society.”

Jetsun attended a convent school in Kalimpong run by Irish Catholic nuns. Her classmates included children from Tibet, Nepal, Burma and West Bengal. While China tightened its grip on Tibet, the school shielded her from the unfolding crisis. She grew up observing and learning from the Dalai Lama, who often discussed her studies. “He encouraged me to attain wholesome education and use it for the benefit of the Tibetan people,” she says.

By the time she was 20, Jetsun had come to understand the magnitude of her community’s political crisis. Around 85,000 Tibetan refugees had arrived in India, and among them were thousands of children who had lost everything—homes, families, culture. Their journey was brutal—many arrived orphaned, malnourished and traumatised.

Women became their caregivers, educators and leaders, playing a central role in building the Tibetan community in exile. “It was my mother’s commitment to our moral and intellectual development that shaped me,” says Jetsun. She now leads the largest Tibetan-run network of schools, and became the first female education minister. “The sheer gravity of the situation drove her to action rather than to despair,” says Dhundup Gyalpo, secretary of the Bureau of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in New Delhi.

One of the community’s most profound acts of resilience was the creation of foster homes for thousands of orphaned Tibetan children. Many women who had lost everything themselves became foster mothers—offering children not just food and shelter, but love, care and cultural continuity.

Jetsun’s sister Tsering Dolma began this work in 1960 by starting a nursery that evolved into the Tibetan Children’s Village (TCV), a network of schools and care homes. “I was involved with TCV from the beginning,” says Jetsun. “At first, I felt unprepared—self-taught and overworked—but determined,” says Jetsun. “Whether it was building a school in Ladakh or starting a campus in the Tibetan settlement in Bylakuppe in Karnataka, I oversaw each work with complete dedication.”

The Dalai Lama understood not just the importance of educating children, but also the necessity for the Tibetan society to adopt a democratic system of governance. He had been a strong proponent of reforms in Tibet, but Chinese authorities obstructed his initiatives. In India, he was able to implement his vision and gradually democratise the Tibetan government-in-exile through the establishment of a people’s representative system. In 1990, he asked Tibetan leaders and community representatives to come together for a special congress to discuss further democratic reforms, including the election of ministers.

“I was in Bangalore when the meeting was held in Dharamsala, and I received a phone call informing me that a special congress had elected me as one of the three kalons—ministers of the Tibetan government-in-exile,” says Jetsun. “I was stunned. I went straight to His Holiness’s office to say I couldn’t accept such a role.” When the Dalai Lama’s secretary explained that it was his wish, she called her husband. Says Jetsun: “He said simply, ‘You have no choice. You must do it.’”

As education minister, she implemented the Tibetanisation programme in all Tibetan schools, including those managed by India’s ministry of education. “I met with India’s education minister and explained how vital it was for the children to learn in their mother tongue. Since 1986, primary-level education at TCV has been in Tibetan. Language, after all, is the root of our cultural and spiritual identity,” she says.

The work she started, she says, must go on. “Education, I believe, is the most essential prerequisite for national development and cultural continuity,” says Jetsun.

Today, the Tibetan children draw strength from the memory of the women of Lhasa who rose in protest, the foster mothers who nurtured orphans, and the Great Mother who gave them the Dalai Lama. “The quiet heroism of mothers and daughters of Tibet has transcended generations,” says Amitabh Mathur, former adviser on Tibetan affairs to the Indian government. “While Tibetan society had not known feminist movements as the west did, the women had always held strong social positions.”

Mathur recalled meeting the Dalai Lama in Paris in 1989. He was posted in the Indian embassy, and was deputed to receive the Dalai Lama and see him off as he passed through the Charles de Gaulle airport. “I was quite resentful that I had been chosen for this late-night duty in the freezing weather. But when I saw him and he held my hand, for some unknown reason I was overcome with emotion.”

Also Read

- ‘US Congress is united on the Tibet issue’: Nancy Pelosi

- 'This Richard is a construct, existing only as much as I give it energy': Richard Gere

- ‘I am confident India will stand on the right side of history’: Penpa Tsering

- ‘The Dalai Lama’s dream of going to Mecca with the Pope’: Rajiv Mehrotra

- The Dalai Lama: The humble giant who can revive democracy

- ‘The planet needs a Dalai Lama’: Claude Arpi

A year or two later, at an interfaith conference in Dordogne, the Dalai Lama walked in with Jacques Chaban-Delmas, the former French prime minister. Upon spotting Mathur and his wife, he announced: “I must greet my Indian friends first.” He walked up to them and invited them to join his table.

Today, from his seat in the tiny hill town of McLeod Ganj in Dharamsala, the Dalai Lama continues to be a moral compass for the global community—spreading the message of integrity, compassion and courage. He never misses an opportunity to highlight the role of women in shaping a kinder world. “My mother was my first teacher,” he says. “It was she who first taught me the priceless lesson of compassion.”

Now 90, the Dalai Lama no longer has the Great Mother to walk with him, but the path she illuminated endures. “India is the land of the Buddha and it is our duty to connect the world through his teachings of peace and human dignity,” says Kiren Rijiju, the only Buddhist minister in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s cabinet. “The Dalai Lama upholds the Nalanda tradition of Buddhism that stretches from the highest Himalayan peaks to the valleys below, and inspires a more peaceful and compassionate world.”