On August 6, 2024, US Ambassador to India Eric Garcetti used social media platform X to urge Indian students to attend EducationUSA fairs across India, painting the United States as a land of opportunity. However, his enthusiasm was swiftly countered by Suren Konthala, a Texas-based Indian tech professional. “Please don’t come to the USA,” he wrote. “Your entire career will be chasing H-1B visas.... It saddens me to hear about or see several Indian students suffering in America. Most of them believed in the ‘American Dream’, not knowing the realities.”

The term ‘American Dream’, first popularised by historian James Truslow Adams in the 1930s, symbolised shared well-being and moral character. Over time, it evolved into a vision of individual success and upward mobility, particularly for immigrants. Indian immigrants have pursued this dream with remarkable success, excelling in technology, medicine and academia. Today, Indian Americans are one of the most educated and highest-earning communities in the US.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which abolished national-origin quotas, marked a turning point for Indian immigration. Later waves, particularly after 2000, saw many Indians arrive on H-1B visas―a temporary, dual-intent work visa for college-educated professionals. However, the bureaucratic challenges of the H-1B and green card processes have left many immigrants in a state of legal and emotional uncertainty.

A major blow to these immigrants’ dreams came on January 20, when President Donald Trump signed an executive order ending birthright citizenship for children born to unauthorised immigrants and those on temporary visas, including H-1B and F-1 (student) visas. The order, set to take effect after February 19, denies automatic citizenship to children unless at least one parent is a US citizen or lawful permanent resident. Experts believe this move clearly contravenes the 14th Amendment of the US constitution.

The Trump administration argues that these children are not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States, but this clashes with longstanding legal precedent, including the landmark case United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898). This case affirmed that nearly everyone born on US soil is an American citizen, regardless of their parents’ status. The supreme court stated, “The amendment, in clear words and in manifest intent, includes the children born, within the territory of the United States, of all other persons, of whatever race or colour, domiciled within the United States.” Subsequent rulings, such as Plyler v. Doe (1982), further extended protections to children of undocumented immigrants, underscoring the enduring relevance of the 14th Amendment.

The Trump administration counters that the framers of the 14th Amendment could not have foreseen today’s immigration complexities. However, even a century ago, marginalised groups like African Americans smuggled into the US faced similar legal limbo. Yet the Congress offered citizenship to their descendants born on American soil. Even far-right Republicans historically upheld birthright citizenship. By contrast, the Trump administration has ignored these legal and historical precedents.

Although a federal judge temporarily blocked Trump’s order, its potential impact on Indian immigrant families is profound. The hardest hit would be H-1B holders and green card applicants, many of whom are motivated by the prospect of birthright citizenship for their US-born children. Without it, these children would also face the endless green card backlog, further diminishing the allure of the American Dream.

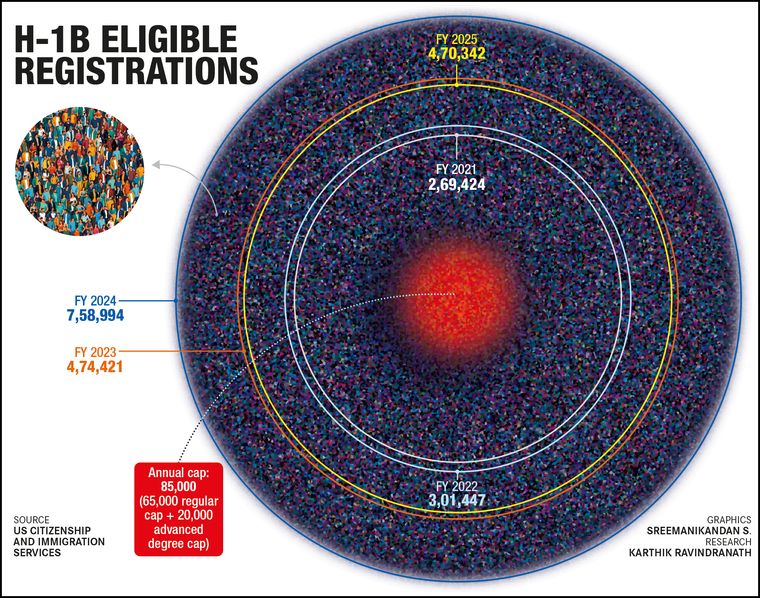

A large section of H-1B holders and their families already live a life of uncertainties. Take the case of Vishnu (name changed), an IT professional from Kerala who is in the US on an H-1B visa. Vishnu was working from India for an American client through one of India’s leading IT contracting firms when he got his visa. The programme caps new visas at 65,000 annually, with an additional 20,000 reserved for those holding advanced degrees from US institutions. Due to high demand, a lottery system decides who gets processed, and in 2020, Vishnu was among the select few.

Despite his good fortune, the pandemic delayed Vishnu’s plans to move to the US. He stayed back in India with his wife Naveena (name changed), who worked in the pharmaceutical sector. In 2022, the couple welcomed a daughter. When the opportunity to move to the US finally arrived, they faced a difficult decision: Naveena and the child could either remain in India or join Vishnu on H-4 dependent visas. However, an H-4 visa would prevent Naveena from working. The couple ultimately decided to move together, prioritising Vishnu’s career opportunity.

“Compared with India, the pay difference is substantial. So, we decided to move to the US, and my wife chose to leave her job. However, once we arrived, we realised that managing with just one income was quite challenging as the living expenses were significantly higher,” Vishnu said.

Ironically, critics of the H-1B programme argue that many H-1B employers―including prominent tech companies―use the programme to underpay migrant workers. A 2020 study by the Economic Policy Institute found that half of the top 30 H-1B employers follow an outsourcing model, supplying staff to third-party clients rather than directly employing H-1B holders to meet internal needs. Indian IT firms, often criticised as “body-shop firms” by detractors, obtained around 20 per cent of all H-1B visas issued between April and September 2024.

While 65,000 is the cap for new H-1B visas annually, petitions to extend an H-1B holder’s stay, change employment conditions or request new employment do not count toward this limit. In fiscal year 2023, 72 per cent of the 386,318 H-1B beneficiaries were Indians―a staggering 279,386 applicants.

Sreenivas (name changed), a senior software architect, represents an earlier wave of Indian professionals who benefited from less restrictive immigration policies. The 52-year-old moved to the US in 2000 through an Indian IT firm and secured a green card in about eight years. “For our generation, obtaining permanent residency was easier,” Sreenivas said. However, he noted that current H-1B holders face significant stress, as their visas are tied to their employers. The fear of losing legal status and the unpredictability of H-1B renewals or green card processing compound this anxiety.

“There have been numerous cases of individuals on H-1B visas facing toxic work environments but feeling trapped, as their limited options for leaving could jeopardise their immigration status,” Sreenivas said. If an H-1B holder loses their job, they must find a new one within a 60-day grace period. The new employer must also file for a visa transfer. Failing this, the individual may switch to a tourist visa to stay legally for another six months while seeking opportunities.

Indian students in the US on student visas also face hurdles. Karthik Mohan, 25, recently earned a postgraduate degree in engineering management from Northeastern University in Boston. He noted that the lottery-based H-1B system discouraged many companies from hiring international graduates, even those with advanced degrees. While STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) graduates like Mohan can avail of up to three years of optional practical training (OPT) work authorisation, many firms remain hesitant about hiring them. Mohan, burdened with a massive student loan, said his immediate priority was finding a job.

Even for H-1B holders who secure a place in the green card queue, challenges persist. The US immigration system caps employment-based green cards at 140,000 annually, with a 7 per cent limit per country. Venkat Parella, a senior software engineer at Microsoft, is in the early stages of green card processing. His employer has initiated the PERM (Program Electronic Review Management) process, the first step in obtaining a green card through employer sponsorship. The process requires proving there are no qualified American workers for the role. Once certified, the employer files the I-140 immigrant petition.

“There is no standard timeline for receiving an I-140,” Parella said. “Holidays, elections, or even company-specific issues like layoffs can influence the process.”

For Indians applying under the EB-2 (professionals with advanced degrees or exceptional ability) or EB-3 (skilled workers and professionals) categories, the wait time is especially daunting. Due to a decades-long backlog, applicants filing in 2025 may face a minimum 20-year wait. Bureaucratic delays could extend this timeline to 100 years or more.

This prolonged uncertainty has significantly impacted Indian immigrant families. Spouses and children, often on dependent visas, find it nearly impossible to plan their futures. Even for families with above-average incomes, the lack of stability casts a long shadow over their aspirations.

In 2013, Indian-American entrepreneur Vivek Wadhwa, testifying before the House of Representatives, predicted that uncertainties created by visa restrictions would push talented individuals to leave the US. He highlighted the struggles faced by families of visa holders tied to the primary immigrant’s status. “The spouses of H-1B workers are not allowed to work and, depending on the state they live in, they may not even be able to get a driver’s licence or open a bank account. They are forced to live as second-class citizens,” he said.

Twelve years later, Wadhwa’s views remain largely unchanged. Although the Obama administration passed a rule allowing spouses of H-1B holders with I-140 approval to work, he described the system as a “bureaucratic nightmare” that trapped skilled workers in uncertainty. “Families are deeply affected―spouses often cannot work, children lose legal status when they turn 21, and no one can plan for the future,” Wadhwa told THE WEEK. “This system does not reward talent; it exploits it.”

Atal Agarwal, a 31-year-old IIT Kharagpur alumnus, now runs a firm offering immigration products to help those stuck in the green card backlog. Having returned to India after working in the US on an H-1B visa, Agarwal said he wanted to avoid being tied to an employer. “There is already a trend of skilled Indian immigrants returning, and this is likely to grow,” he said.

Anurag Singh, an IIM Lucknow alumnus with experience in US-based private equity funds, observed that “bright Indian talent” is increasingly “crowded out” of US opportunities. He said fewer US recruiters visited IITs because of the uncertainty of the H-1B lottery. “If you’re aspiring to settle in the US, the path from India is extremely hard. The system needs to shift to a merit-based approach instead of a lottery,” Singh said. He also noted that Indians capturing 70 per cent of H-1B visas showed misuse, as it was unlikely such a large share of global talent resided in India.

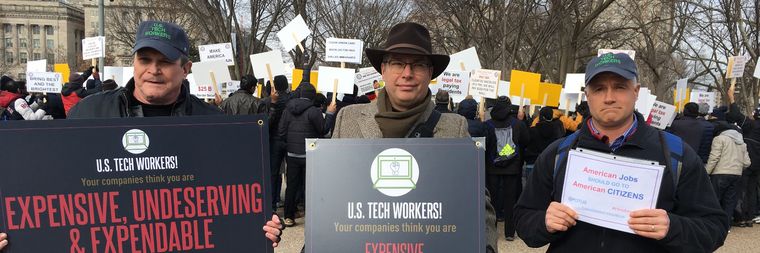

Anti-H-1B advocacy groups share this view. Kevin Lynn, founder of US Tech Workers, argued that the H-1B programme is exploited to replace American workers with cheaper foreign labour. “The US already has a visa programme for exceptional individuals―the uncapped O-1 visa. Most H-1B workers are ordinary, not innovators. Nearly half of top H-1B sponsors are IT outsourcing firms, not high-tech innovators,” Lynn said. He pointed to a lawsuit by Purushothaman Rajaram, a naturalised American citizen of Indian origin, against Meta, alleging that the company preferred hiring non-citizens on H-1B visas to pay lower wages. While a federal judge initially dismissed the case, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the decision in June 2024, allowing the case to proceed.

Lynn contended that H-1B’s design inherently exploited workers. “The programme isn’t abused; it is working as intended, shaped by business interests,” he said. Experts like Erik Ruark of NumbersUSA suggest reforming the system by allocating visas by salary. “If an employer truly needs an H-1B worker for a unique position, they should offer a premium salary,” Ruark said.

Trump’s return has reignited the H-1B debate, with criticism coming from both the far right and left. Bernie Sanders, a prominent left-wing senator, argued that H-1B visas displaced “good-paying American jobs with low-wage indentured servants”. He called for prioritising “the best and brightest” instead.

Wadhwa countered that critics like Sanders failed to understand the realities of a global economy. “Instead of demonising skilled immigrants who contribute billions to the economy, Sanders should focus on fixing America’s broken education system,” he said. Wadhwa argued the backlash against H-1B workers revealed underlying racism and resentment toward Indian Americans. “This community pays about 6 per cent of federal income taxes while making up only 1.5 per cent of the population,” he said.

Sree Sreenivasan, CEO of digital media agency Digimentors and president of the South Asian Journalists Association, said Indian Americans were now under increased scrutiny. “For years, nobody paid attention to our contributions. Now they are paying attention, and we are feeling the impact,” he said.

India views skilled professionals as a cornerstone of its ties with the US. “India-US economic ties benefit from the technical expertise of skilled professionals, with both sides leveraging their strengths,” said Randhir Jaiswal, spokesperson for the ministry of external affairs. Indian IT firms, however, reported reduced dependence on H-1B visas, focusing on local hiring and technological advancements.

Despite this, Wadhwa believes the H-1B visa will remain a flashpoint in India-US relations. “Indian tech companies account for a significant share of H-1B visas, and restrictions directly impact their operations,” he said.

With Trump back in the White House, the situation for immigrants looks increasingly complicated. During his first term, Trump imposed significant restrictions on the H-1B programme as part of his ‘America First’ agenda. While his rhetoric has softened somewhat, especially in the company of tech billionaire Elon Musk, one of his closest advisers, it could shift at any moment. Trump’s core MAGA team remains staunchly against the H-1B programme. Key allies like Steve Bannon, who served as White House chief strategist, are advocating for its complete termination. Although Trump has not yet announced any drastic changes to H-1B policies, his second-term agenda is steeped in anti-immigration rhetoric.

Trump has already launched a large-scale deportation drive, using military aircraft to repatriate undocumented immigrants. Reports allege that deportees were shackled and denied water and bathroom access during their flights, sparking outrage. The crackdown even led to a diplomatic clash with Colombian President Gustavo Petro, who refused to accept US military planes carrying deported immigrants. Trump retaliated with threats of steep economic sanctions, including an initial 25 per cent tariff on Colombian imports, escalating to 50 per cent within a week. He also vowed to impose strict financial penalties, implement travel bans on Colombian officials, and revoke their visas. Although Petro eventually relented, he condemned Trump’s policies, writing on X: “You can try to carry out a coup with your economic strength and your arrogance.... But I will die true to my principles. I resisted torture and I resist you.”

Also Read

- What tech giants told their H-1B employees as many get stranded outside US after visa renewal delay

- ‘US has been an immense beneficiary of talents from India’: Elon Musk defends H-1B visa programme

- H-1B visa: Trump government to make visa rules tougher, more restrictive

- What is MEA's stand on Trump's new H-1B visa regulations? Spokesperson Randhir Jaiswal says...

- How will the GCC segment in India shape up post the H-1B visa challenge?

- Be it Trump tantrums, H1-B visa fee hike or punitive tariffs, India-US trade thrives

India, meanwhile, has expressed willingness to accept undocumented migrants if their Indian origin can be verified. However, American authorities have intensified actions targeting Indian immigrants. The department of homeland security has started visiting gurdwaras in New York and New Jersey, citing concerns over illegal immigration and criminal activity. Sikh organisations have criticised these actions, calling them an affront to religious sanctity. “We are deeply alarmed by the DHS decision to eliminate protections for sensitive areas and then target places of worship like gurdwaras,” said Kiran Kaur Gill, executive director of the Sikh American Legal Defence and Education Fund. “This sends a chilling message to immigrant communities nationwide.”

As Trump’s anti-immigrant policies escalate, both legal and undocumented Indian immigrants are on edge. Reports suggest that many Indians are rushing to hospitals for C-sections to deliver babies before February 19, the deadline for Trump’s birthright citizenship ban. Now, with Trump openly musing about a third term, his disregard for constitutional norms raises fresh concerns. As critics point out, his administration seems to operate as though the constitution and the department of justice are irrelevant.

John C. Coughenour, the federal judge who stayed the birthright citizenship order, made that clear during the hearing. “I have been on the bench for over four decades,” said the judge, who was appointed by president Ronald Reagan. “This is a blatantly unconstitutional order. Frankly, I have difficulty understanding how a member of the bar would state unequivocally that this is a constitutional order. It just boggles my mind.”