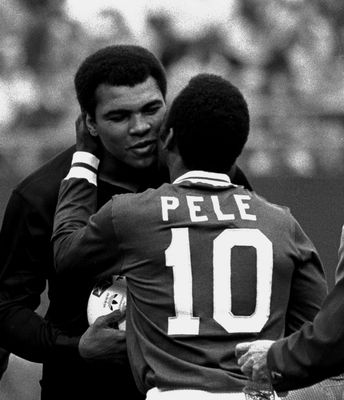

Now, he belongs to the ages.” The sentence, uttered first in reference to Abraham Lincoln’s death, now describes Pele.

Edson Arantes do Nascimento, Pele to the world, was the greatest footballer of all time. He was the distilled spirit of Brazil and the sum of its football greatness.

The thinker Arthur Schopenhauer described talent as hitting a target no one else can hit, and genius as hitting a target no one else can see. He may just as well have been describing Pelé.

The striker introduced a new level of skill and technical ability to Brazilian football, using both his feet and his head in manners others had not. Every early description of his career notes this emergence of an innovator. They also note the joy of a child playing with a ball.

Named after the inventor Thomas Edison, Pele married science with art. He transformed play into a mix of magic and technique, which epitomised and popularised the description of football as jogo bonito―“the beautiful game”.

“A man of genius is unbearable, unless he possesses at least two things besides―gratitude and purity,” wrote the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who reflected deeply on what makes any individual exceptionally great.

Pele spoke often and from the heart about his gratitude to God, to football, to the Brazilian people and to Brazil itself. Clean and unspoiled, Pele’s character made his greatness visible early on. As early as the 1960s. In a country where football was primarily played and followed by elite whites and the middle- and upper-classes, Pele’s success changed the perception of black people. Those days, black players were systematically discriminated against, excluded from professional leagues and the national team, and otherwise faced significant barriers. Pele’s success made the sport more accessible to and popular among people of all races.

In his 1964 book Viagem em Torno de Pele, Brazilian journalist Mario Filho wrote: “Pele is more than a great player. He is a symbol of Brazil and of the joy of football. He has brought happiness and pride to millions of people around the world, and he will always be remembered as one of the greatest of all time.”

Pele was born to Dondinho and Celeste Arantes on October 23, 1940, in Tres Corações, a picturesque and socially active town in the southeastern Brazilian state of Minas Gerais. Rich in culture and dotted with colonial buildings, the rural town had a population of about 20,000 in the 1940s, and was described as quiet and peaceful, surrounded by lush forests and rolling hills.

The family lived in a thatched-roof house with a small yard in a neighbourhood of other small houses and narrow, dirt streets. This is where the young Edson put foot to ball for the first time. The family lived in poverty and often struggled to make ends meet.

Pele spent much of his time playing football in the streets and in the small yard of his home, and he developed his skills and technique through hours of shoeless practice. By all accounts, the family supported his love of football.

The home was also where he learned the values of hard work and determination, which would serve him well throughout his career.

In his autobiography, Pele wrote about how he and his friends would play with a ball made of rags and how football gave them a sense of purpose and hope.

As a child, Edson had excellent ball control and was able to dribble past defenders with ease. He was also a powerful and accurate shooter, able to score goals from far and near.

“When I was three or four, my father would take me along to Vasco (club) training sessions,” he told The Guardian in 2006. “Whenever I could I used to nip into the goal and play around, and whenever I managed to stop a shot I’d shout, ‘Good one, Bilé!’ or ‘Great save, Bilé!’ (a goalie team-mate of his father). Because I was young, I somehow distorted the nickname and said that when I grew up, I wanted to be a goalie like ‘Pile’. When we moved to Bauru, this ‘Pile’ became ‘Pele’.... And then one boy, I don’t remember who, started to tease me by calling me Pele. So, thanks to that goalie Bilé, and a classmate’s little joke, I became Pele. Now it is known across the world, and I do not mind it so much.”

Pele was six when the family moved to Bauru, a city in São Paulo, where his father was a centre-forward with a minor league club. At nine, he dropped out of school and began to dream of playing football professionally, with the help of and coaching from his father. At 13, Pele caught the eye of Waldemar de Brito, one of the pioneers of Brazilian football and manager of the Bauru Atletico Clube. There, Pele began his career.

In 1956, while still 15, Pele made the three-hour journey across the Serra do Mar Mountains to the Atlantic seaside city of Santos on the São Paulo coast. There, he joined the Santos FC Academy, rising quickly from the junior team to the first team reserves and the starting lineup before the end of the year. He was still 15 when he signed with Santos, the only first-division Brazilian team he would play for.

Club led to country, and Pele made his international debut in 1957. For one beautiful decade that followed, Pele was Brazilian football. From 1957 to 1965, he was the league’s top scorer, turning Santos into the world’s team, the team that everybody wanted to see lift the cup again and again.

Pele was just 17 when he played his first World Cup. He recalls in his autobiography how, in preparation for the tournament in Sweden, he fell and hurt his knee; some people thought his career was over. He writes about the determination and perseverance he needed to overcome the injury and regain his form. He scored six goals in the World Cup, making him one of the top scorers of the tournament. He would go on to score six more in three other World Cups, making him one of the most successful strikers at the tournament.

In his autobiography, Pele wrote about the excitement and sense of accomplishment he felt after scoring a brilliant goal (one of three) against France in the semifinal. He scored two in the final against Sweden.

“What Pele did in that World Cup was enough,” says Brazilian coach Silas Eduardo Severino, early trainer of Endrick Felipe, the teen sensation Real Madrid recently signed for around €70 million. “Even today, there is no way to compare Messi or Maradona with him, at 17! He made us all believe. He did not know what the Europeans had; did not know what he had within himself. And what he had within himself was much greater than all the others.”

By the time his second World Cup came, the opponents were more aware, says Severino. “The whole world already knew that he was dangerous, and they marked him heavily. Their objective in every game was to stop Pele. By the 1970 World Cup, he invented a new type of play that was more touch and pass, looking for the right time to break out. He scored one of the goals of the tournament. He would make passes without looking. He just knew instinctively a teammate would be there. That is football genius.”

After the 1970 final against Italy, Pele would collapse in tears on the field and was later quoted as saying, “I cried because of the emotion, because of the joy, because of the pain.”

Carlos Alberto Torres, the captain of the Brazilian team that won the 1970 World Cup, wrote on a cover blurb for Pele’s autobiography: “Pele was a true global icon and a symbol of Brazil. He inspired so many people and brought joy to so many lives. He was an incredible ambassador for football and used his fame and influence to promote social justice and make a positive impact on the world.”

If what he did on the field was genius, what he stood for outside was equally inspiring. His success made others, especially black Brazilians, believe in themselves. Says Severino: “Pele was very young, but if he could, I believed I could. If Pele became a global superstar without playing in Europe, I could, too. He made us believe!”

On November 19, 1969, when Pele scored his 1,000th goal (including in unofficial matches), he dedicated the milestone to the children of the world, famously saying, “The ball is round, the game lasts 90 minutes; everything else is just background noise.”

Though he stopped playing for Santos in 1974, he signed with New York Cosmos the following year. The New York Times reported at the time: “Pele, known throughout the world as the king of soccer, agreed yesterday to sign with the New York Cosmos, who will reportedly pay him $7 million in a three-year contract.”

He played in the North American Soccer League from 1975 to 1977. This stint would awaken interest for football in the US, a country where it had failed to gain acceptance as it was competing with the more established American football, baseball and basketball major leagues.

On October 1, 1977, in a farewell friendly between Cosmos and Santos, which the former won 2-1, Pele retired for the final time. He had played one half for each team, and had scored against Santos in the first half.

“Pele was a great player, a real symbol of our country. He gave so much to the game and to Brazil,” wrote Ronaldo, one of Brazil’s greatest strikers, after Pele’s death.

For nearly five decades after his professional career, Pele maintained global relevance and used his fame and influence to advocate for various causes.

A national hero, Pele has been the subject of numerous books, films and other works of art, and has received numerous awards for his contributions to football and to Brazilian culture. In a unique tribute, he became one of the first living persons to be featured in a video game, Atari’s Pele’s Soccer, in 1980.

Pele was also involved in efforts to promote peace and understanding between different cultures and countries. In 1978, he was invited to play in a charity match in Haifa, Israel, as part of the nation’s 30th anniversary celebrations. He agreed to play, but on the condition that a Palestinian player be included on the opposing team. The Palestinian player, Mahmoud Abbas, later became the president of the Palestinian National Authority.

He worked with FIFA as an ambassador against racism and with UNICEF to promote children’s rights. In 1978, Pele was awarded the International Peace Award for his work with UNICEF. He had a soft spot for children. He had seven of his own, from three marriages.

In 1994, Pele was appointed as a UNESCO Champion of Sport in recognition of his ability to use his influence to promote international collaboration and contribute to world peace and security.

He returned to the pitch in 1995, playing in a charity match to raise money for the victims of an earthquake in Kobe, Japan. He scored a goal and then immediately collapsed on the pitch. It was later revealed that he had suffered a heart attack and was rushed to hospital.

The following year, he was invited to speak at the United Nations for its 50th anniversary celebrations. “Sport,” he said, “is the only international activity in which every person can participate, regardless of race, religion, or political beliefs. It is the one activity that can bring the world together.”

In 1997, he received an honorary knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II and, two years later, the International Olympic Committee named him ‘Athlete of the Century’. The same year, TIME magazine named him in its 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century list.

Between 1995 and 1998, Pele was also Brazil’s Extraordinary Minister for Sports. And as an administrator, he thought deeply and passionately about the game. When Brazil hosted the World Cup in 2014, Pele told French journalist Mustapha Kessous in an interview THE WEEK published ahead of the tournament: “I do not want to give the impression that I am the World Cup. The most important thing is the image of my country and its influence throughout the world. I remember no one really knew about Brazil in 1958 when I went to Europe. When I arrived at the training camp in Switzerland, the Brazilian flag had a circle instead of the diamond. From then on, I have had just one wish for the World Cup―it should be used to help my people and my country.”

He was also mindful of the practicalities surrounding such an event. “Spending too much on stadiums is out of the question because the money is coming from the people,” he said in that interview. “We cannot afford to find ourselves with these white elephants that will not have any use after the World Cup. We need to build schools and universities.”

Having worked for charity ever since he retired, Pele, in 2018, launched the Pele Foundation, which has had a long and significant impact on the lives of people around the world. He continued his charitable work even while battling cancer. “He was a true role model and an inspiration to so many people around the world,” wrote Brazilian superstar Ronaldinho. “Pele was an extraordinary player, but he was also an extraordinary person. He was kind, humble and generous, and he used his fame and influence to help others.”

Pele’s death marks the end of an era in football, says Severino. “Pele will always be an exact reference, the perfect example of what an athlete should be―a comrade, educated, elegant, calm. His legacy will continue to serve as a guide for all. His time with us―what he showed us, and what he taught us―now belongs to the world.”

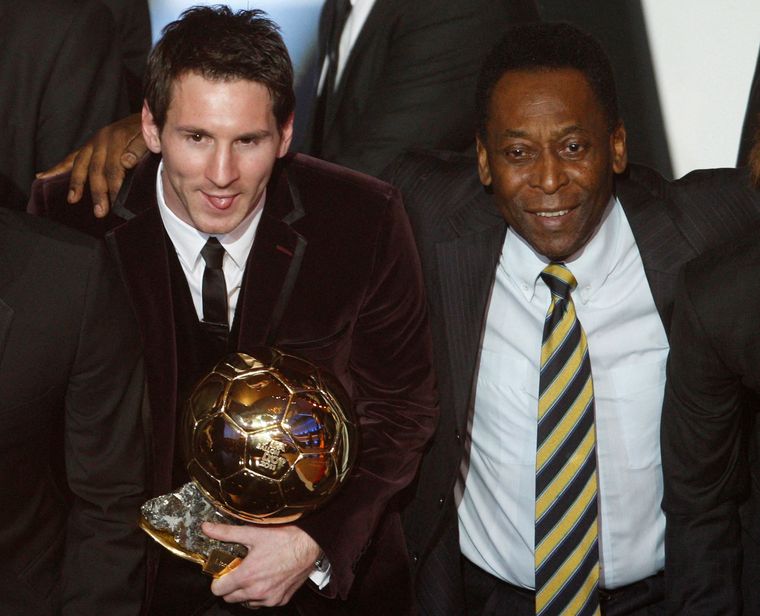

On the heels of a World Cup that canonised Lionel Messi as football’s new god, we revisit the words of the Argentine hero: “For me, Pele was the best player in history. He was the only player who could do things no one else could do.”

In that 2014 interview, Pele acknowledged the greatness of Messi, but also added: “When Messi scores 1,283 goals and wins three World Cups, we will talk about it again. We do not need to compare people. Football changes, records are made to be broken, but it will be difficult to beat mine.”

Even Diego Maradona, who was often pitted against Pele in the debate of who the best was, once said that “Pele was the greatest”.

To fill the interlude between life and death, we humans often seek the comfort of words that give context to and sum up the value of life. We find them on the site of Pele’s foundation: “Pele is a big word. As big as love. Belief. Dreams. He is football’s greatest ambassador, and the gold standard by which everybody else lives. Pele is Brazil’s green and yellow. He is the magic in the air for every game that’s played.”

Perhaps having given thought to what he leaves behind, Pele had told Kessous: “After my death, I would like people to remember that I was a good person who always wanted to unite people and draw communities together. And for them to remember me as a good player... People ask me all the time, ‘When will the next Pele be born?’ Never! My mother and father have closed the factory.”