Sixty years from 1962 may be a mere speck in the sands of time. But it has been good time to win the battle for the hearts of the Arunachali people who first witnessed the swift advance of Chinese military coming down in organised columns from the northern mountains.

In ’62, bewildered by the sudden invasion, the few locals inhabiting the border area in the north Lohit valley—belonging to the Kaman Mishimi and Meyor tribes—did not know how to react.

A lot has changed since then. Arunachal Pradesh is now the only state in the country where people greet each other with a patriotic “Jai Hind” (victory to Hindustan).

Dr Sototlum Nayil, a state government health official posted in Anjou district, told THE WEEK: “My parents worked as porters in the 1962 war effort. The guides of the Chinese military were also local people from the other side of the border who are of the same ethnic stock as us. So there was not a great deal of animosity.”

“But times have changed now. The locals now know where they belong and why,” Dr Nayil, himself a Kaman Mishimi, adds.

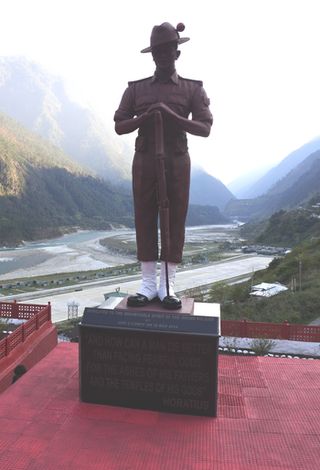

The brunt of the fighting took place in the Namti plains. Yet, nothing could be so perfectly deceptive like Namti. An expansive and idyllic picture-perfect valley with that abundantly overpowering smell from the lush pine groves in the surrounding mountains even as the river Lohit scurries by.

Situated in Arunachal Pradesh’s easternmost Anjou district, the battle at Namti qualifies to be among the most successful fightbacks by the vastly outnumbered and outgunned Indian soldiers against the invading Chinese.

“So fierce and intense was the battle and so much of ammunition used that till recently, the teeth of the saws used by woodcutters in and around Namti would get damaged because of many bullets embedded in the trees,” says Dr Nayil, speaking about the time before tree-felling was banned in entire northeast India in 1996.

The military objective before the Indian forces in the area in September-October 1962 was to defend Walong, five km to the south of Namti, against the advancing Chinese forces.

Walong’s utility lay in the fact that despite being a very isolated post that could be reached only after days of tracking, it had an airstrip where only the Otter, a light transport aircraft, could land. The Indian Air Force operated about 40 Otters before it was completely phased out in 1991.

In 1962, the nearest road-head from Walong was at Tezu, about 230 km to the south.

Now, a well-laid road scythes across the windy plain and climbs up to the last military post of Kibithu almost on the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and to the last Indian village of Kaho.

Till the 1962 war, the road—now named after India’s first Chief of Defence Staff General Bipin Rawat—was just a mule track. In the very thinly populated region, it was primarily used for trading purposes and linked up to Rima, a prosperous settlement across border under Yunnan province.

This road is of immense strategic importance now to guard the border and is the main passage for the movement of soldiers and equipment other than the helipad at Kibithu and the advanced landing ground (ALG) at Walong.

The Battle at Tiger’s Mouth

In 1962, the Chinese captured the last Indian outpost of Kibithu on October 22 and began the rapid advancing southwards by proceeding along the west bank of the Lohit river.

A platoon of 4 Sikh—who were flown by Otter aircraft to Walong from September 26 onwards—took positions on dominating points on the surrounding mountains of the Namti valley while the D company of 6 Kumaon had taken up positions at Ashi Hill.

On October 25, a column of 600-700 Chinese had descended on the plains. Catching the enemy by total surprise, the Sikhs opened fire inflicting huge casualties when the enemy massed around the wire obstacles.

Even as a company of 2/8 Gorkha Rifles relieved the Sikhs, the Chinese began attacking the Namti defences of the Indian forces from the evening of October 25.

Wave after wave of attacks continued for the next two nights, till October 25, but the Indians could not be dislodged. Because of its impregnability and the inability to be broken into, the Chinese named this place ‘Tiger’s Mouth’.

The Kumaonis, Sikhs and Gorkhas had successfully staved off the Chinese offensive at the gates of Walong for the time being.

But the unrelenting Chinese war machine regrouped and consolidated resources for a final offensive on November 15-16 by crossing the Lohit river and climbing the highest ridge line which was occupied the Sikhs, Gorkhas and the Kumaonis.

An all-out fierce war broke out and the Chinese kept coming, even as the Indians kept on fighting with depleting stocks of ammunition and other war-like equipment besides running out of food. The zeal of the Indian soldiers was all the more striking as they knew that no reinforcements or ammunition could be expected. In many places, it was a fight to the last man and the last bullet.

Finally, Namti gave way to the Chinese on November 16 after being outflanked by the well-stocked and well-equipped Chinese. Hundreds of soldiers died on both sides.

India’s NEFA defence strategy

Before the 1962 war, the military defensive strategy in North East Frontier Agency (NEFA)—as Arunachal Pradesh was known until 1972—hinged around a three-tier system of engagement.

The outermost tier comprising border outposts would act only as “symbols of authority and controlling routes of entry”. The mandate for the men in these outposts: Don’t fight but delay the enemy and then fall back to firm bases in the rear.

The middle tier was organised on positions that the border outposts were dependent upon and to which they would fall back when attacked. These middle tier set ups were sufficiently in depth to increase the logistics problem of the Chinese.

Also read

- Revisiting 1962 war with China: When India's prestige was in a shambles

- How India handles China will determine success of foreign policy

- What's the role of a partly undefined 4,075km border in Sino-Indian conflict

- Had India employed its Air Force in 1962, there would have been fewer casualties

- There is no easy way for India to catch up with China

The last tier was the “defence line” where the main battle would be fought and from where offensives could be launched whenever the situation demanded. It was located on positions to cause sufficient logistical problems to the Chinese and also to catch them off-balance.

In NEFA, hostilities had begun earlier. On September 8, 1962, about 600 Chinese soldiers surrounded the newly-set up Dhola post of the Indians. The setting up of the Dhola post in itself was a result of the ill-devised “Forward Policy” from 1961 onwards—believed to be among the main reasons for kick-starting the war and the subsequent loss by India.

In turn, the “Forward Policy” implementation order for NEFA issued on January 10, 1962 by the Eastern Command was based on the mistaken notion that the Chinese would not react like they did. More so, in view of the fact that the Chinese military had greatly enhanced its presence in Tibet after 1960—in significantly greater numbers than was required to quell and control the Tibetan uprising. This fact was also pointed out in October 1960 during the Military Intelligence Review 1959-60 in New Delhi.

Even as late as August 1962, the Director of Military Operations at the headquarters of the 4th infantry division declared that the Chinese would not react and were in no position to fight”.

The mistaken belief in the Indian defence establishment was that the Chinese were more focused on consolidating their hold over Tibet and in opening up communications.

And surprisingly, nor did the Army’s General Staff at any point of time make a submission of the basic requirement of more troops in form of two additional brigades and relevant resources for NEFA before the “Forward Policy” policy was to be implemented.

Only on September 22, 1962, did the defence minister hold a meeting in Delhi where it was decided to “throw the Chinese out as soon as possible”. Clearly, it was easier said than done as history would later record for posterity.

While being militarily sound, this strategy was more on paper. The number of additional troops was never made available nor was the plans executed in the NEFA operations of October-November 1961.

Also bordering on the incredulous was the sudden October 4, 1962 disbanding of the XXXIII Corps that was handling the NEFA operations and sudden setting up of the IV Corps—a decision that is unparalleled in the annals of military history due to its arbitrariness and suddenness.