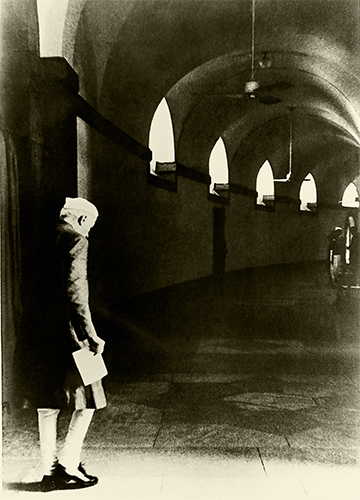

Fools rush in where angels fear to tread, goes an old proverb. India’s political and military leaders did exactly that in 1962.

On February 4, 1962, idealist Jawaharlal Nehru’s peacenik home minister Lal Bahadur Shastri declared: “If the Chinese will not vacate the areas occupied by her, India will have to repeat what she did in Goa.”

Indeed, what India had done in Goa six weeks earlier had startled the world—it had freed the Portuguese enclave by sending its Army. Here was an Asian country of starving millions, newly freed from colonial yoke and partitioned into two, militarily taking on a European power and prevailing. The action did strain India’s ties with the western world, including Great Britain from where most of the India’s arms and spares were coming, as also the United States that was keen to rope India into an anti-communist alliance. But Nehru, who had been a passionate campaigner against colonialism, did not care.

In India’s neighbourhood, the action rang alarm bells: is India rising militarily and getting assertive? In China, with whom India had a long-standing border dispute despite warm political and diplomatic relations, it brought back nightmares of Indian military actions such as the 1904 Younghusband expedition when a force of just about 3,000 British and Indian troops simply walked across the Himalayas, massacred thousands, and captured Tibet’s capital, Lhasa.

That was an expedition that India had forgotten, but the Chinese remembered and still remember. Why? The simplest explanation is that the two nation-states have differing perceptions of their pasts. India believed—rather still believes—that the nation was born in 1947 and the aggressions of its past rulers are sins; the Chinese, on the other hand, look at their past with pride and at themselves as inheritors or legates of the Mings, the Qings and other imperial dynasties that ruled China. If Indians are ashamed of their British, Mughal and sultanate past, communist China has no qualms about projecting itself as the inheritor of the Middle Kingdom.

Indeed, the Chinese had been disputing and negotiating over the border that Sir Henry McMahon had drawn 10 years after the Younghusband expedition. But when Shastri made the threat hardly a month after the Indian Army’s Goa action, it did sound aggressive. Moreover, on December 5, just a fortnight before the Goa action, orders had gone to the Indian Army’s eastern and western commands “to patrol as far forward as possible from our present positions towards the International Border as recognised by us. This will be done with a view to establishing additional posts located to prevent the Chinese from advancing further and also to dominate any Chinese posts already established in our territory.”

That was no routine order, but a part of the forward policy that the Army had adopted to counter the Chinese whose patrols along the McMahon Line were often foraying into Indian territory. In effect, the policy involved getting behind Chinese lines, and creating about 60 outposts there so as to cut off their supplies and force them to return to their side of the line.

Indeed the policy would have been good military tactic, had India executed it with the required military muscle. The fact, however, was that India lacked the required strength to carry it through. The show of force in Goa had been a robust assertion of political will, but that was no great military action—the Portuguese military in Goa was nothing but a few hundred troops and armed boats.

Not only had Nehru failed to invest in the military, but he was advised on his military policy by the hot-tempered left ideologue V.K. Krishna Menon who essentially distrusted the British-trained military brass. Thus Menon had not only got a weak-willed P.N. Thapar to succeed the dashing K.S. Thimayya whom he had disliked as Army chief, but also got Lieutenant General B.M. (Bijjy) Kaul, an Army Service Corps officer who, as his detractors say, had bullshitted his way up, first as the chief of the general staff, and later as commander of the crucial 4 Corps. It was this corps that was designated to defend NEFA, the present Arunachal Pradesh which China had been coveting.

As chief of the general staff, Kaul and his men aggressively implemented the forward policy, despite warnings from field commanders like Lieutenant General Umrao Singh whose 33 Corps had been guarding NEFA before Kaul arrived with his 4 Corps. “So irrational was their confidence,” wrote Geoffrey Blainey in The Causes of War, “that they decided on the eve of the war to evict Chinese troops from a stretch of border where the Indians were outnumbered by more than five to one, where Indian guns were inferior, where the Indian supply route was a tortuous pack trail and where the height of the mountains made the breathing difficult and the cold intense for the reinforcements who marched in cotton uniform.”

Naturally, friction arose at several points and clashes ensued. A skirmish in June caused the death of scores of Chinese troops. Early September, a small Chinese unit crossed to the south side of the Thagla Ridge that Indian troops had been occupying, and tried to cut them off. Within days, permission was given to all forward posts and patrols to fire on any armed Chinese who entered Indian territory. “Instead of coercing or deterring the Chinese, it provoked them into responding with brute force and strength,” notes Air Vice Marshal Arjun Subramaniam (retd) in India’s Wars: A Military History 1947-1971. Naturally, skirmishes followed.

Early October, Kaul, now commander of the 4 Corps in the east, sent troops to secure south of the Thagla Ridge. The troops had not been acclimatised, and two Gurkha soldiers died of pulmonary oedema. A Rajput patrol of 50 troops was surrounded by hundreds of Chinese at Yumtso La, and outnumbered 20 to 1. Cover fire was given with mortars for them to retreat, but 25 Indian and 33 Chinese troops were killed in the fight. It was now clear that the situation was escalating into a hot war.

By mid-October, the Chinese were seen building up massively around the Thagla Ridge. By now bravado was getting to its peak, with Kaul wanting to show he was leading from the front. “Kaul himself displayed unnecessary bravado by trekking for days at the front line at altitudes above 10,000 feet without proper acclimatisation,” writes Subramaniam. “Not surprisingly, he was supposedly taken ill with pulmonary oedema on 18 October before the main battle began and evacuated to Delhi....”

In the field, the Indian side miscalculated again. Expecting an attack by three regiments on October 19-20, the 7th Indian Brigade stood defending the five bridges across Namka Chu river. The Chinese waded through the waters and struck. The defenders fought well, but were soon felled, and their phone lines cut. The brigade was permitted to withdraw, having suffered severe losses.

By now, Kaul’s superior, eastern Army commander, Lieutenant General L.P. Sen, arrived on the scene. After an aerial inspection of the region, he ordered two infantry battalions and some artillery to “hold Tawang at all costs,” and flew back.

Hardly had Sen left, when the Chinese, now reinforced, moved towards Tawang. The Indian side judged that there was no way Tawang could be defended, and wisely withdrew, even as the Chinese occupied it. The guns fell silent in NEFA, except for a few skirmishes in Walong and elsewhere.

But in the western sector, in Aksai Chin, the Indians put up a brave show, the fiercest having been at Galwan Valley and Pangong Lake where, ironically enough, the show has been repeated recently.

Galwan had been surrounded since August, but on October 20, the Chinese assaulted and captured the post, along with several others in the Ladakh sector. Western Army commander Lieutenant General Daulat Singh ordered that troops at posts which survived be asked to withdraw, so as to consolidate and launch a counter-attack with three brigades.

The scene in the east continued to be chaotic. Instead of reorganising the forces, the Army spent its time and energies in shuffling commanders, throwing the lower formations into confusion. By now, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai had written to Nehru proposing a negotiated settlement of the boundary, withdrawal by both sides to 20 kilometres from the current positions, offering to withdraw from NEFA, and a freeze in the situation in Ladakh. Nehru replied on October 27, expressing eagerness to settle the matter, but refusing a 20 km withdrawal after facing aggression into 40 or 60km. Restore status quo ante bellum, he insisted.

Fighting resumed on November 14, after about three weeks of lull. Indian troops now moved to defend Bombdi La and Se La, but found themselves poorly equipped for staying and fighting at high altitudes. Still they built up there and stayed in force. But the Chinese attacked elsewhere.

Kaul, who had resumed command after his illness, ordered an attack on the Chinese position at Rima from Walong on November 14. Two companies of a Kumaon battalion captured a hill, but as they rested in exhaustion, the Chinese counter-attacked. As the Indians withdrew, the Chinese pursued them to Walong, forcing the brigade at Walong to withdraw to Lohit valley, suffering huge losses.

Now Kaul sent the most desperate message ever sent by any commander in free India. “The enemy strength is now so great and his overall strength so superior that you should ask the highest authorities to get such foreign armed forces to come to our aid as are willing to do so... it seems beyond the capability of our armed forces to stem the tide of the superior Chinese forces which he has....” Yes, an Indian Army commander was putting it on record that Indian troops could not fight the war any longer, and better get foreign help!

By now, fighting had resumed in the Ladakh sector, too, where the western command had positioned a brigade at Chushul so as to prevent the enemy from making a lunge for Leh. The enemy finally came in a frontal attack on November 18, but the defenders stood their frozen ground. Pushed back, the Chinese quickly encircled the Indian positions, and attacked from three sides. Facing decimation, the Indians withdrew to Chushul village to take what they thought would be a last stand.

Luckily for those few, the enemy never came—the Chinese stopped at their claim line. By November 18, they had all of Aksai Chin.

All the same, fighting continued in the east, with the Indian side building up fast, but continuing to make mistakes. Instead of concentrating their ten battalions and artillery, the 4 Division spread out their assets over the entire stretch of road from Se La to Bomdi La.

Also read

- How India handles China will determine success of foreign policy

- What's the role of a partly undefined 4,075km border in Sino-Indian conflict

- Had India employed its Air Force in 1962, there would have been fewer casualties

- There is no easy way for India to catch up with China

- War of 1962: How Kumaoni, Sikh, Gorkha soldiers fought back valiantly in Namti

But the Chinese did not come by road. The headquarters could not believe their ears when they heard that the enemy came in several battalion strength through mountain tracks which British and Indian mountain recce aces had discovered and traversed early in the 20th century. The enemy hit the defenders somewhere in the middle of their thin line, and thus cut off the more than 10,000 forward troops at Bomdi La. The reinforcements sent to save them were subjected to heavy fire, and forced to withdraw in complete disarray.

The defenders at Se La put up a brave fight, pushing back five Chinese attempts to dislodge them. Soon the Chinese proved superior in tactics, too, they went straight to Thembang and cut the supply route to Se La. By now the field headquarters of the brigade itself was threatened, and Brigadier Hoshiar Singh requested for permission to withdraw.

But his corps commander, Lieutenant General Kaul, was flying around Walong while his two superiors, Lieutenant General Sen and General Thapar, were sitting in his office. With no idea about what was happening, both sat tight, waiting for Kaul to return and decide.

Kaul arrived after nightfall, by which time the Chinese had begun to encircle Se La, too. After a short meeting, they sent a ridiculously worded—yet shocking—order saying, “You will hold on to your present positions to the best of your ability. When the position becomes untenable I delegate the authority to you to withdraw to any alternative position you can hold.... You may be cut off by the enemy.... Your only course is to fight it out as best you can.”

Soon A. S. Pathania, commander of 65 Brigade at Dirang Dzong, ordered a withdrawal to the southern plains. If the enemy still attacked, they were even allowed to abandon their tanks and flee to the plains. The result was chaos. With no one to command them, the force at Dirang Dzong simply scattered down to the plains. Many were killed or captured by the enemy.

By now, Kaul was completely out of touch with the ground realities. Unaware that the force at Dirang Dzong had withdrawn, Kaul ordered a column to reinforce them, overruling Hoshiar Singh who pointed out that such a move would weaken Bomdi La.

Just as Hoshiar Singh had feared, hardly had the column moved out when the Chinese struck. Though the defenders put up a brave fight through the day, by the evening of November 18, the brigade had no go but to withdraw to Rupa.

In the annals of military history, the night of November 18 would go down as one of the most bizarre ones that any army had ever gone through. First Hoshiar Singh received orders from the 4 Corps to withdraw to the foothills. Just as he began the movement, came another order from General Kaul to stay put and defend Rupa.

By then it was too late. As he turned back and moved towards Rupa, Hoshiar Singh saw the Chinese already pitching their tents and setting up their pillboxes around Rupa. The brigade now moved towards Chaku further down the hills, but was subjected to heavy attack. And hardly had the remaining troops reached Chaku and dug up when the enemy came in search of them and struck them from three sides. Whatever was left of a mighty brigade scattered into the plains in the next few days.

On the evening of November 20, Nehru appealed to the US for bombers and fighters. Washington ordered a carrier into the Bay of Bengal, but ordered it back the very next day. Not only had India been defeated, but also abandoned.

The Chinese victory was complete. Having gained more than what they wanted, they declared a unilateral ceasefire from midnight of November 21, and even moved back their forces from most of the captured land, but keeping the strategically vital stretches including Aksai Chin. And within days they began repatriating the prisoners through Bomdi La. For India, the war ended with 1,383 killed, 3,968 captured, 1,696 missing, and its prestige a shambles.

In three years, however, the Indian Army would make a remarkable recovery, and turn itself into a awesome war machine. And Shastri, who had made that boast on February 4, 1962, would order an incredibly bold counterattack on Pakistan, with hundreds of tanks lunging towards the prime cities of Lahore and Sialkot, and forcing a ceasefire. He would thus redeem his own and India’s honour.