If one colour-codes the Punjab elections, one would find the contests have been between white and blue in the past five decades. The present assembly polls have witnessed three more colours: yellow, green and saffron, turning it into a riot of colours, thus making the choice difficult for the people.

Politicians in Punjab had adopted particular colours for their turbans to project a distinct identity for themselves. Congressmen have mostly worn white turbans, though former prime minister Manmohan Singh popularised sky blue. Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) leaders have traditionally worn navy blue turbans. As Punjab politics has been bipolar since the state was carved out in 1966, these two colours dominated. If Chief Minister Charanjit Singh Channi is often seen sporting a white turban, SAD chief Sukhbir Singh Badal generally prefers the trademark navy blue.

The Aam Aadmi Party, which is making a renewed bid to gain power, has picked yellow; its chief minister candidate, Bhagwant Mann, prefers yellow turbans. “I adopted yellow as I am a hardcore Bhagat Singh fan—this was his colour,” he told THE WEEK.

The farmers’ union leaders who have formed the Sanyukt Samaj Morcha predominantly wear green turbans. Its president and chief ministerial candidate Balbir Singh Rajewal is green himself. Saffron nationally denotes the BJP.

Punjab is witnessing a multi-cornered contest for the first time. Every seat has five candidates and every party is promising to change Punjab. The state faces many deeply dark issues such as corruption, unemployment and drug menace. The winner of the elections on February 20 will surely face some hard challenges.

“We are winning with a huge margin,” Mann claims. The AAP has been leading in almost all the pre-poll surveys. The sentiment on the ground also affirms the same. The party emerged second, after the Congress, in the 2017 elections but suffered a setback as almost half of its 20 MLAs left it. Since then, the party has been trying to build its organisation at the grassroots. The support for the AAP is most pronounced among the lower middle class as the party’s social media outreach has been able to sell its narrative of efficient hospitals and good schools in Delhi. “I am a hardcore Akali Dal supporter. But my children and relatives have been gravitating towards the AAP,” said Darshan Singh, a farmer from Jatana Uncha village in Fatehgarh district.

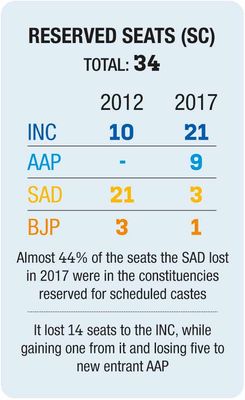

The SAD, which is fighting to regain its lost glory, has even brought in its nonagenarian patriarch, Parkash Singh Badal, into the fray. For the first time, SAD chief Sukhbir Singh Badal is his party’s CM face. After breaking its alliance with the BJP, the SAD roped in the Bahujan Samaj Party to woo the dalit voters (32 per cent) in the state. The SAD had already promised to make a dalit the deputy chief minister. The party continues to retain its vote base in rural areas, but the younger voters are looking for newer options.

“[Some] non-regional parties are showing up and trying to take over [the state] once again, which is the biggest threat to Punjab and punjabiyat,” said Sukhbir Badal. “We will not let non-regional parties bring dark days into Punjab again.”

While the AAP and the SAD fancy their chances, the stakes are much higher for the Congress. “We were happy when Channi was made chief minister. This will certainly help the Congress get votes from the dalit community,” said Satnam Singh, a Jalandhar resident. How the energised dalit vote-bank responds to appeals from the Congress, the AAP and the BSP will influence the results in many seats, especially in the Doaba belt.

Infighting is the main issue in the ruling Congress. There is confusion about who will be the party’s CM face—Channi or Navjot Singh Sidhu, the state party president. “Only the Congress can defeat the Congress,” said Sidhu in a press conference, adding that his party will perform better than last time.

Despite its alliance with Captain Amarinder Singh’s Punjab Lok Congress and Sukhdev Singh Dhindsa’s Shiromani Akali Dal (Sanyukt), the BJP is finding it hard to gain ground. It is for the first time that the party is coming into a big brother role in an alliance in Punjab. The BJP inducted several Sikh leaders from other parties to bolster its chances. “Only the BJP has the blueprint to double farmers’ income,” said Iqbal Singh Lalpura, chairman of the National Commission for Minorities, who is the BJP candidate from Ropar. “Local parties may have opposed the farm laws for over a year, but they do not have a blueprint for farmers.”

Also read

- Former cricketer Harbhajan Singh in AAP Rajya Sabha candidate list from Punjab

- 'Other candidates in Moga are buying votes': Sonu Sood on seizure of car

- 'All corrupt people have teamed up against us': Kejriwal on Khalistan connection accusations

- EC extends ban on roadshows, processions in poll-bound states

- Bhagwant Mann hopes to lead the AAP to victory in a multi-cornered fight

- Manifestos should be legally binding, says Bhagwant Mann

The other party trying its luck in the current elections is the Sanyukt Samaj Morcha—floated by 22 farmer unions which were part of the yearlong agitation at Delhi borders against three farm reform laws. It will be a tough fight for the Morcha in its inaugural bout, as it lacks the electoral infrastructure that traditional parties have. The party has also not received a poll symbol, so its candidates will contest as independents. But its CM face, Rajewal, is confident. “I have seen Punjab from close quarters for the last five decades,” he said. “Even if I am the only one in the assembly, I will make things difficult for the government by raising issues and asking questions.”

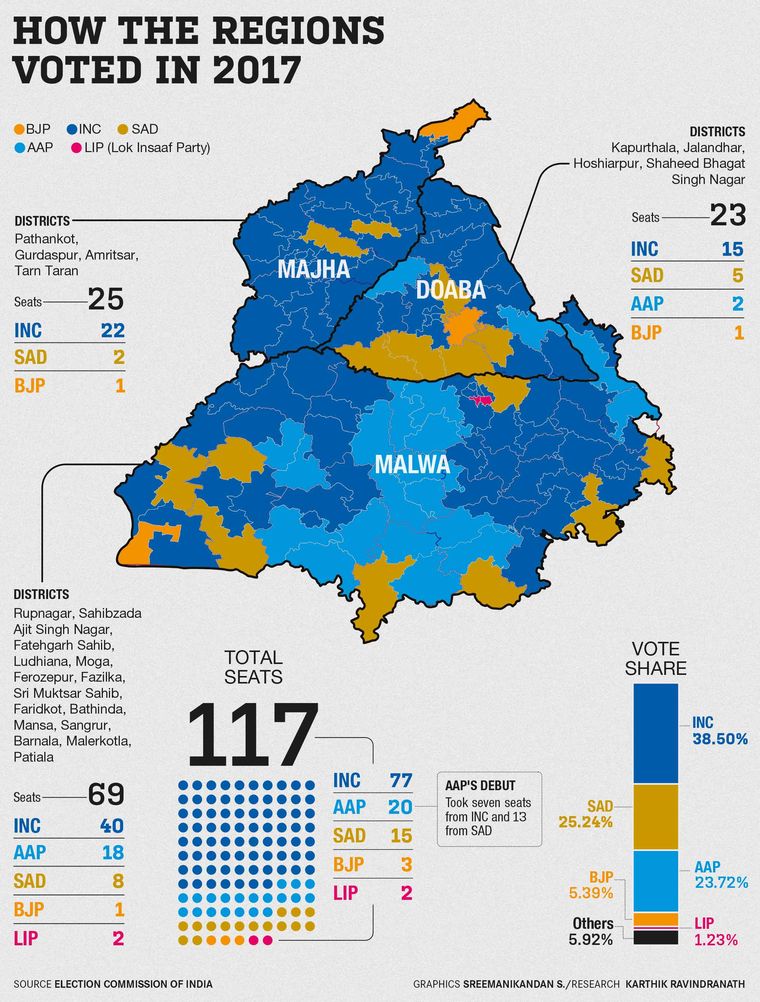

If the turban colours give a peek into the political affiliations of people, the political choices in Punjab also differ on the basis of the three regions in the state: Majha, Doaba and Malwa. The Majha region comprises the border districts of Amritsar, Tarn Taran, Gurdaspur and Pathankot. This region generally has small landholdings and is backward.

The Doaba region, which is between the Satluj and the Beas rivers, has a higher concentration of dalits. It is also called the NRI belt of the state. The Malwa region, which comprises districts of Patiala, Ludhiana, Sangrur, Ferozepur and Faridkot, has always dominated Punjab politics. Malwa is a land of big landlords and claims the largest chunk of seats in the assembly—69 out of 117 seats.

The AAP was a bigger gainer in Malwa in 2017, but could not repeat the feat in Majha, the traditional stronghold of the Congress. This time, the SAD hopes to perform well in the Doaba region because of its alliance with the BSP.

Winning Punjab will not be easy for any party. The political hue this border state chooses will surely have an impact on national politics, too.