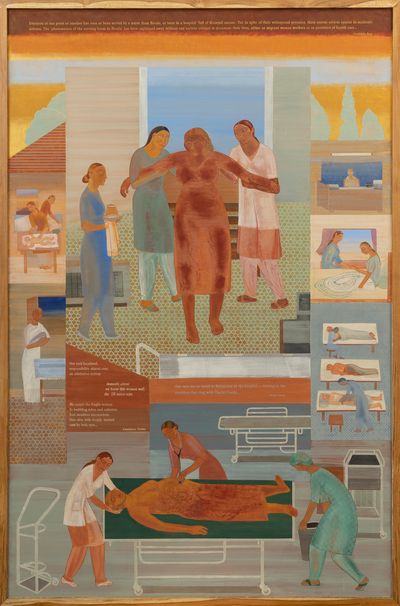

Touched by the compassion of the nurses who tended to her ailing, ageing parents, artist Nilima Sheikh expressed her gratitude in the way she knew best—through her art. The Vadodara-based artist initially made 10 small paintings on paper. But the magnitude of their dedication, and her appreciation of it, demanded a larger canvas. And thus ‘Salam Chechi’, a five-panel painting on wood, came into being.

‘Salam Chechi’, a glowing tribute to nurses, especially those from Kerala, was first showcased at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in 2019. Sheikh thought it to be the right place to show her work as it would be seen by people who had knowledge of the profession or were connected with it. The paintings that depict glimpses of caregiving are now with the Kiran Nadar Museum of Modern Art in New Delhi.

Indian nurses are both compassionate and professional, says Sheikh. “They deal with the hardships of living in a metro,” she says. “Delhi is not an easy place for young women, especially at night. They deal with the long shifts. They deal with the fact that they never get due acknowledgment for the work they do.”

While her parents were unwell, there was not a day when Sheikh was left without help. The nurses she hired from an agency knew their job and were always on time, she says. “My mom died at the age of 86,” she says. “She had a hip fracture and health issues in the last seven years or so of her life.’’ Sheikh’s mother, a pathologist, was also interested in art; an amateur gardener, she had published books on gardening.

Sheikh’s doctor father lived to102; he gave up practice at 95 after a surgery. “Only in the last five years of his life did he need some support from an attendant,” she recalls. “He was worried the caregiver stress would affect my professional life, and agreed to nursing support.”

Her father encouraged her to make a studio in their Delhi home so that she could work there. “I could work fairly free of anxiety because the nurses took good care of my parents,” she says. The nurses worked in two shifts. “One nurse never left before the other came,” she says. “If there was ever any issue, the proprietor of the nursing agency would herself stand in.”

They say doctors make poor patients. But Sheikh says her parents were patient. “My dad was very positive,” she says. “He briefly had herpes, which can be painful. That was the only time I heard him expressing pain and irritation. He was very forbearing otherwise, and the nurses liked him a lot.”

Growing up in a family of doctors, she was aware of the profession of nursing since childhood, having seen them in the general hospital where her father worked and her aunt’s nursing home. “We would have Christmas parties mainly for the nurses there,” she recalls.

A history graduate, Sheikh did extensive research before embarking on her art project. She read up on nursing in the western world and in India. “I read somewhere that Florence Nightingale had planned to visit the nursing colleges that were set up in India, but she did not,” she says.

Also read

- Best Hospitals Webinar, 2021: THE WEEK honours excellence in health care

- Dr Jame Abraham of Cleveland Clinic on when doctors feel vulnerable

- Health care gets an upgrade with lessons from COVID-19

- THE WEEK-Hansa Research Best Hospitals Survey 2021

- Nurses put the care in health care, more so during the pandemic

- Challenges of being a male nurse

It took Sheikh about eight months to finish the painting. She usually works on canvas or cloth, but chose free standing panels for this one. “I used to look at a lot of 14th and 15th century paintings in Europe, especially altarpieces, which made me go in for this kind of format,” she explains. Sheikh painted on them with casein, a glue-like extract from milk or soy milk, blended with pigments.

About her focus on the Malayali nurse, Sheikh says, “I felt that their professionalism and commitment was in some way inbuilt. I wonder where it comes from. Maybe the level of education in Kerala, or the sense of mission and commitment that came through the Christian ethos has permeated into those in the nursing profession.” Most of the nurses who took care of Sheikh’s parents were Malayalis. “There was a Sikh nurse—also from a community committed to seva. She was very competent,” she says.

While the nurses were all thorough professionals, they had their own ways of being friendly, says Sheikh. “One of the early nurses who took care of my father was very efficient,” she recalls. “She got a better job in a hospital. Hospital jobs are always preferred because of the shorter working hours. Also, it was closer to her daughter’s school. So she had to leave, and we were worried. To allay our anxiety, she spent hours training me how to clean the nebuliser and do all the things she used to do. That was very lovely.”

There was another nurse whom her father was very fond of. She had severe back pain. “I took her to my doctor. The nurse was diagnosed with TB of the spine,” says Sheikh. “We helped her through it. She recovered well and was back at work.”

Sheikh is still in touch with some of those nurses. “We exchange greetings during Onam,” she says, smiling.