Oorjita Lath had not stepped out of her Gurugram house or met anyone since mid-March. But on April 1, when vaccinations opened up for the 45+ age group, she went to a facility nearby to get her shot. A day later, she had fever, fatigue and aches that people said were known side-effects of the vaccine. When, five days later, her condition had not improved, she consulted a doctor through telemedicine, who recommended she get a Covid-19 test done. She tested positive. Subsequently, so did her husband and two daughters, all of whom are in home isolation, grappling with bone-breaking pain and fever. The doctor feels she picked up the bug from the vaccination centre.

Lath may have got the bug because the vaccine had not even had time to get cracking with producing antibodies. But across hospitals, doctors and health workers are testing positive in droves, despite having received both doses of the vaccine. A few had to be admitted, too, because of existing comorbidities. Reinfections in patients—around 1 per cent—may not be that rampant, but the numbers are enough to establish that acquired immunity does not last long. And at a time when fresh cases are rising, reinfections add to the load.

Then, there are patients returning to hospitals with complications developed as a result of the damage the disease wreaked on them. “We are seeing patients with lung fibrosis and kidney problems, all caused by their encounter with the virus,” says Dr Suranjit Chatterjee, Indraprastha Apollo Hospital’s senior consultant in internal medicine. By one rough estimate, 5 per cent of Covid-19 cases (which is a high number, say doctors) suffer from a condition called long Covid, which manifests itself in different ways—tremors even months after recovery, chest spasms, breathlessness, anxiety and erratic heartbeat. Not every doctor recognises that these are not just psychiatric issues that can be solved with counselling. The body, which had to go into fight mode to deal with the virus, produced adrenaline, and even months later, the adrenaline spikes continue. The treatment is through low-cost medication to counter the hormone, but it requires trained professionals to recognise this need.

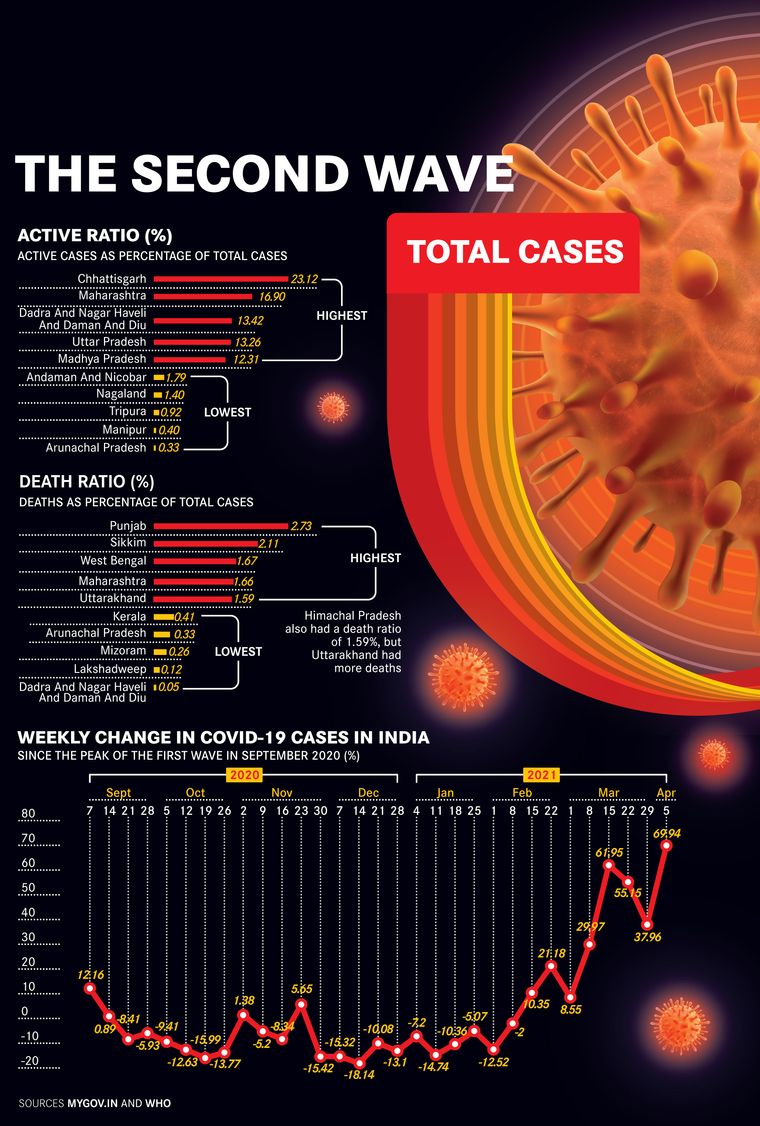

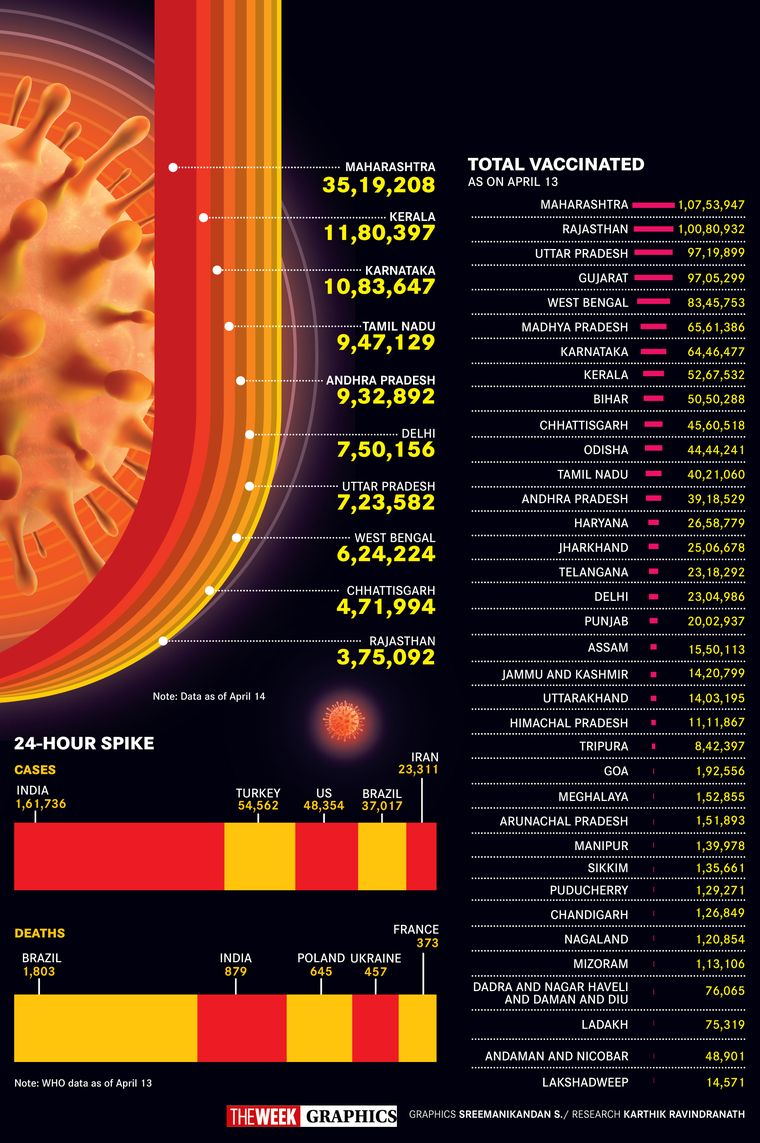

Just when the nation was smugly patting itself on the back for having managed the pandemic rather well as compared with other countries, it resurged with a vengeance. Ambulance sirens have begun pealing again, almost continuously in some parts. Comparisons with other countries often do not give the full picture. So, saying India has surpassed Brazil to second slot with highest daily cases may have policy makers rushing with different explanations. Look at it this way: In barely a month since the second wave, India has already surpassed its own previous highs of daily new cases, and the dying continues at alarming numbers. Last year, it took four months into the “wave” for deaths to reach the highest toll of 1,114 on a single day (mid-September). This time, within two months of the surge, the single-day death count has crossed 1,000. Union Health Secretary Rajesh Bhushan was forced to admit that this was a cause for worry. While the death rate itself has not gone up—it is around 1 per cent as in last year—in sheer numbers it might increase as the case load rises to new highs.

On April 13, Delhi alone reported 72 deaths and more than 13,000 fresh infections. Only a few weeks ago, its daily rise was down to two digits and there were days with no recorded deaths. During its worst time last year, the daily hike was below 9,000. Daily cases are increasing by over a lakh nationally, and we do not even know whether this is the crest of the wave, or if the peak is yet to come. “This virus is like nothing we have seen before,” says Chatterjee. In this fresh round, there are more symptomatic cases than asymptomatic, say doctors. And the below 40-population has been hit in a bigger way.

Over the last one year, the nation had prepared itself for the ongoing war against the virus. An ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ turned to desi production of both low-cost personal protection equipment and high-tech life support systems. It ramped up pharmacological production and even developed vaccines. It developed a team of administrative officers, health workers and scientists who, having learnt through experience, were now expert hands and not shooting in the dark. With a varied arsenal, one would have thought the next battle would be easier to win.

But the SARS-CoV-2 virus had tricks up its sleeve. It came up with an updated version of itself, mutating into several variants, some of which are adept in the Houdini-like skills of immune escape and RT-PCR test evasion. Most importantly, though, the virus found a huge breach in the opponent’s defences—pandemic fatigue. With neither individuals nor systems stressing on the Covid-appropriate behaviour of masks, hand hygiene and social distancing, the virus found it easy to infect swathes of population. Perhaps it need not even have mutated to cause the present havoc, the territory was its for the taking. A population that had laid down its armour and was hedonistically celebrating festivals and marriages, congregating in droves at markets, election rallies and the Kumbh, was foolishly challenging a virus it had underestimated.

But was it really underestimation? Or, was it a case of deliberate blindness? There were examples from other countries, like the UK and Brazil, which went through second waves deadlier than the first. It is true that the virus has behaved unpredictably and all models that predicted its run have failed miserably. “There were colossal mistakes in the reading of the epidemic at the community level, and misleading narratives didn’t help,” says Samiran Panda, head of Indian Council of Medical Research’s epidemiology and communicable diseases division. “There were premature reports, based on limited sampling, which declared that over half the population in Delhi, Pune and Vadodara was already seropositive and people began seeing a false dawn. Firstly, those studies were based on limited numbers. Secondly, three cities do not represent the entire nation. The National Serological Survey done by ICMR earlier this year clearly indicated that over 75 per cent of Indians were uninfected and therefore vulnerable.”

Also read

Yet, in the haste to push the pandemic behind, authorities prematurely wound up many of the special Covid-19 facilities that had been set up. To give the economy a boost, almost all restrictions, except in educational institutions, were lifted, the government leaving it to the people to be responsible for themselves. Thus, Pandemic 2.0 quickly stretched health capacities. Be it the corridors of upscale Lilavati hospital in Mumbai, where patients are spilling into corridors, or the Government Medical College Hospital in Nagpur, where 65 patients are crammed in a facility for 19, the situation is grim everywhere. And as Covid-19 cases flood hospitals, regular OPDs are shutting down again, creating a parallel health crisis. In Gujarat, crematoria are collapsing under the pressure of endless funerals. In Delhi, too, authorities are scrambling to find more space to bury the bodies.

Every resource is facing a crunch. Testing capacities have reached their limit. “Till we get more kits, how can we test anymore?” asks Tripti Shirke of SLR Diagnostics in Mumbai, which stopped taking fresh requests on April 10. The government has had to stop exports of remdesivir, the antiviral used for treating cases that land up in hospitals. “As practitioners, we now know what works and can manage cases better. However, our doctors and health workers have been fighting the war for a year now, and the fatigue is setting in. Many are themselves ill, or suffering long Covid. We are in for a tough ride over the next two months,” says Dr Shuchin Bajaj, founder-director, Ujala Cygnus group of hospitals and core member of Project StepOne, an initiative started last year by doctors and paramedics nationwide to provide free treatment and care to patients.

As numbers began spiralling out of control, authorities did what they do best—indulge in a political slugfest. The Centre coined the poetical Vaccine Maitri term to describe its vaccine diplomacy, but back home, there is neither maitri (friendship) nor diplomacy where vaccines are concerned. The fight between the Centre and states (mostly non-BJP led ones) is an ugly and no-holds-barred one. In the most paradoxical of situations, states reported vaccine shortage and even shut down centres temporarily, while the Centre came out with figures highlighting the poor vaccination coverage among target groups, and worse, the high rates of vaccine wastage. “It is bad vaccine management,” claimed Bhushan.

Even mild-mannered Union Health Minister Dr Harsh Vardhan went ballistic, accusing states of diverting attention from their failures at handling the pandemic and making “deplorable attempts to spread panic”. He accused the Chhattisgarh government of having the “dubious distinction of being perhaps the only government in the world to have incited vaccine hesitancy”, since the state had initially refused to use Covaxin. Amid the squabbling, the Centre kept releasing graphs to show how its vaccination ramp-up was the fastest in the world, its coverage the most comprehensive.

The blame game has quietened a bit now, as states take a hard look at themselves and face even harder decisions of imposing fresh lockdowns. The nightmares of last year’s lockdowns have not left collective memories. States have the headache of holding state board examinations after CBSE announcement of cancelling X and postponing XII.

The narratives around the vaccine itself are many, and conflicting. Indifference towards vaccination is perhaps more responsible than vaccine hesitancy for the sluggish turnouts. Then, there are those who considered the vaccine as their licence to go back to the past ‘normal’, only to belatedly realise the limitations of these vaccines. “These are disease-modifying vaccines, not disease prevention ones,” says Panda. The message, however, has driven home only after a string of reports of post-vaccine infections.

While the demand from Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal and Maharashtra Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray to open up vaccination to all may come from a political posturing, there is clearly a need to have a more nuanced approach towards vaccination. Right now, the Centre procures vaccines from manufacturers and allots them to states, whose task is to distribute them to centres and coordinate the vaccination. The Centre’s policy is that with limited supplies, for the present, only the 45+ age group is eligible. India, however, is a young country, and 65 per cent of its population is below 35. This group also has comorbidities like autoimmune disorders and cancers, but so far, is ineligible for vaccination. “We should not have a situation of black markets and stampedes, but the vaccination process should become more open now, so that those who need the vaccine get it, as against those who want it,” says Bajaj.

The Centre’s tight control over vaccination has already resulted in Serum Institute of India having problems with AstraZeneca for reneging on international commitments. The grand plan of garnering the international market did not take off as envisaged when manufacturing capacities remained limited. You cannot claim to be vaccinator of the world, and then regulate exports. To give desi industry a fillip, the Centre was also slow in allowing other firms in. On April 13, it finally announced that it will give Emergency Use Approval without mandatory clinical trials to Covid-19 vaccines developed and manufactured in other countries, which have been cleared by the drug regulatory authorities of the US, European Union, the UK and Japan, or which are listed by the World Health Organization for emergency use. This announcement, following close to the import approval to the Russian-made Sputnik vaccine (which will subsequently also be manufactured by Indian partners like Dr Reddy’s) will augment the vaccine basket and, hopefully, inject the much-needed vigour into the vaccination programme. Perhaps, in a later move, these vaccines may also be available commercially.

None of these vaccines, experts are quick to warn, will stop the chain of transmission, and any premature lowering of guard will be extremely foolhardy. Bad as the situation now seems, it could get much worse if the virus spreads rampantly across the country. So far, the bulk of the cases—85 per cent—are restricted to 10 states, including Maharashtra, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, Gujarat, Delhi, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. Admittedly, more testing, as is done in these states, also throws up more cases. Its spread into Chhattisgarh and Uttar Pradesh, which were previously rather unaffected, is a portent that needs to be heeded. With the poorer infrastructure of the less developed states, India could head for an unprecedented crisis. “Vaccination will continue to be important in limiting hospital admissions, in addition to a strong adherence to Covid-19 appropriate protocol,” says Panda. Vaccine acquired immunity will augment the natural acquired immunity in ending the pandemic one day.

And where exactly is that day? “Given that all predictive models have failed, we can only go back to history and understand the progress of the Spanish flu a hundred years ago. It came in big waves and then disappeared on its own after around two years, without a vaccine,” says Bajaj.

There is hope that scientists might develop a vaccine that can break the chain of transmission. Till then, the masks stay firmly in place.

with Pooja Biraia Jaiswal