In 1971, Gopivallabpur village of Paschim Medinipur district went the Naxalite way and became one of the many “liberated zones” in West Bengal.

A seven-year-old boy was among the few villagers who swam against the Naxalite tide. As class war raged around him, he told his father, a school teacher, that he wanted to join the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. He was interested in sports, and had been drawn to RSS volunteers who were coaching the local boys in football, athletics and stick fighting, after school hours. They also told them about the lives of their leaders, about a political party called Jana Sangh and about its founder Syama Prasad Mookerjee.

All through his school years, the boy quietly worked for the RSS; his worried father kept it a secret from the villagers. When he turned 20, the young man left home to become a full-time RSS member. He seldom touched base with the family thereon.

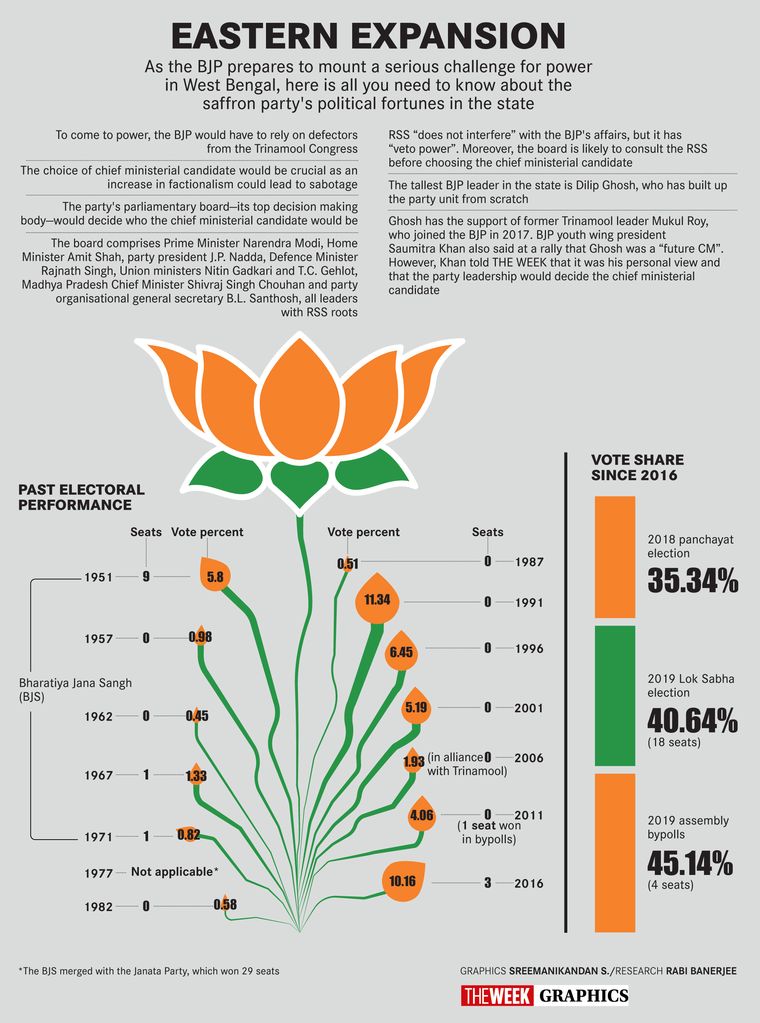

Almost 40 years later, Dilip Ghosh is president of the BJP in West Bengal. His supporters say he will be the next chief minister. Election to the state’s legislative assembly is due in May, and Ghosh has already mounted an aggressive campaign to unseat Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee and her Trinamool Congress party.

Though the BJP has not named anyone as its candidate for chief ministership, Ghosh is seen as the frontrunner. He is a formidable man, a controversial figure, who has rarely balked at making inflammatory speeches and vitriolic verbal attacks against leaders of other parties. Some of his critics have called him “venomous”.

Such opinions have hardly deterred Ghosh; he is laser-focused on his goal of ousting Mamata and forming a BJP government. His eye-for-an-eye approach to deal with political violence has caused the Trinamool Congress some concern. He has proclaimed that, once in power, he would punish those who have wronged him and his party men. “I assure you, I will make their lives miserable,” he said at a recent rally, referring to policemen who were allegedly helping the ruling party or framing his followers.

This approach has won him a legion of admirers, especially in rural Bengal. Everyone who dislikes Mamata, even those who have traditionally supported the Congress or the left, seems to have found a new leader to rally around.

Five years ago, before he was deputed to the BJP, Ghosh was a politically untested pracharak, but a powerful one. Today, he is the most popular leader in the state, barring Mamata. His morning meetings over tea, which drew just about 50 people four years ago, are now rallies attended by thousands. The police have had to intervene to control the crowds and have pulled him up for not taking permission for holding rallies. He has shrugged it off, saying he could not be blamed for the growing popularity of the morning meeting.

At a typical Ghosh event in rural Bengal these days, people jostle to catch a glimpse of him. He starts his speech by attacking the state machinery and the chief minister. His colourful words have brought upon him 45 court cases, but he just goes to a higher court to get bail and comes back with a sharper tongue.

At times, he has even asked BJP supporters in villages to tie up and beat the police if they foisted false cases on them. “Note down the names on their uniforms,” he has often said. “Give me your diaries when we form the government in May. I will see what to do with them.”

The audience laps it up, roaring in approval. According to a BJP leader, many of his recent public meetings in Bengal, including some in Kolkata, had record attendance. Not even Mamata or former chief minister Jyoti Basu could draw so large crowds in certain rural pockets, said the leader.

Said a state BJP general secretary: “Mamata Banerjee organises rallies all over Bengal with police protection. But Dilip-da just turns up in villages, and women leave their cooking to see him. The youth run to the rallies. It is simply amazing.”

Bankim Ghosh, who was a minister in the last Left Front government a decade ago, joined the BJP in 2019. “I had seen how people would burst into applause when Jyoti Basu took the mike,” he said. “I recently accompanied Dilip Ghosh to a place near Nandigram. Much like at Basu’s meetings, people started clapping as he took the stage. He has become a mass leader. I will not compare him to Basu, because Basu was a man with a different calibre. Dilip Ghosh has his own style, different from both Basu and Mamata. Today, he is more popular than Mamata, though I accept she is also very popular.”

But isn’t Ghosh’s style annoying to the educated class? Bankim said: “We missed such a leader in Bengal. It is because the left could not produce such a leader that Mamata has continued as an autocratic chief minister for ten years. Whether you like him or not, Dilip Ghosh has given people the strength to combat Mamata. There have been many attempts on his life. But he has not cared, and has set such an example that the people have now created a wall of resistance against the Trinamool in the rural areas.”

The former Marxist leader said change was imminent in Bengal. “People will vote for the BJP if elections are held today,” he said. “The situation is similar to 2011, when we lost to the Trinamool.”

Ghosh works from morning till midnight, with a discipline that has drawn appreciation from the party’s central leadership. “I have seen very few leaders who are so dedicated,” BJP national secretary Arvind Menon told THE WEEK. Menon is in charge of the party in Bengal along with Kailash Vijayvargiya and Amit Malviya. “From early morning to late night, you can see him either at rallies or organising workers. He is a fighter who has resisted the Trinamool’s torture. We are extremely happy to have a person like him under whose leadership we are going to the polls. We are poised to cross 200 (of 294) seats. If we fail, you call me and seek an explanation.”

If the BJP does win, will Ghosh be the chief minister? Menon did not want to talk about it, but the prominence given to Ghosh on the party’s posters is an indication that he is the main contender.

“I have not been with the party long enough to have the final word,” said Bankim. “But I have been in politics since 1980. The BJP does not declare a chief ministerial candidate anywhere. But the way Dilip Ghosh is being projected, he will likely be the next chief minister.”

The preparations are almost complete. For the past seven months, Ghosh has been video-calling Bengalis in 30 countries, asking them for ideas on how to govern Bengal and turn it into an industrial state. “They are delighted,” said Ghosh. “They told me they would like to come back and work in Bengal.”

Though an RSS man, Ghosh does not harp on hindutva in his speeches in rural Bengal. Some Muslims there seem to appreciate it. His speeches mainly consist of trenchant attacks on the state administration. He accuses it of being beholden to the ruling party.

The urban folk of Kolkata, however, are not too enthused by Ghosh’s words. Said Aanindyo Bhadra, a software engineer who lives in Belgachia in the city: “Dilip Ghosh is a hardcore Hindu leader. But he has to learn a lot from [Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister] Yogi Adityanath. Yogi acts tough, but talks mildly. Ghosh should not forget that he would have to deliver on what he says. So, it is better if he speaks decently.”

Sankar Sarkar, a trader from the Muslim-dominated Malda district, disagreed. “He is the perfect person to tackle Mamata,” said Sarkar. “Have we all forgotten the language of Marxist leaders? And the politics and the virulent words of Mamata not too long ago? She even organised vandalism in the legislative assembly.”

Recently, Ghosh told Nobel laureate Amartya Sen to mind his language. Sen was embroiled in controversy as the Visva-Bharati university said that his family had encroached upon its land; that the family had taken more land than had been allotted long ago for Sen’s residence on the campus. Denying the allegation, Sen said it was the BJP’s revenge for his relentless criticism of the Narendra Modi government. He asked all political parties in Bengal to unite against the BJP. Calling Sen a political opportunist, Ghosh said, “He is diverting the issue and taking refuge in the political space.”

Dilip Ghosh has transformed the BJP’s organisational machinery in Bengal in just a few years. It was nonexistent when the Left Front was in power for three decades. In the last five years, Ghosh has drafted a lot of communist cadres into the BJP as well as some of their important leaders. Many prominent Trinamool leaders are also in his party.

RSS insiders say he has the ability to make hard choices and is unwavering in his objectives. He once declined a ministership in the Modi government, preferring to focus on his plan to oust Mamata.

Ghosh became a full-time RSS pracharak in 1984. He told his parents that he wanted to participate in nation building, not home building. He has lived mostly in eastern India, though he has also worked in western India and in the south. In 1999, RSS leader K.S. Sudarshan appointed him his office secretary. Sudarshan had been in charge of the RSS in eastern India in the early 1990s and had taken a liking to Ghosh. Sudarshan became RSS sarsanghchalak in 2000, and as his secretary, Ghosh met top BJP leaders such as A.B. Vajpayee and L.K. Advani. He also knew Modi, a pracharak like him who was chief minister of Gujarat.

Sudarshan was one of the stern RSS chiefs. Unlike his predecessor Rajendra Singh, he did not have a cordial relationship with prime minister Vajpayee. He was apparently miffed that Vajpayee could not help the RSS achieve its dreams of building the Ram temple and abolishing Article 370 of the Constitution. He saw Vajpayee’s National Democratic Alliance government as a continuation of the United Front government.

Ghosh saw the friction up close. “Of course, Sudarshan-ji wanted all these implemented,” he told THE WEEK. “But how could we do all that? Vajpayee-ji did not have the mandate. It is true that pracharaks across India were frustrated. But we understood his problem.”

When the NDA lost the Lok Sabha election in 2004, few RSS workers shed tears. In fact, there was talk that the RSS had refused to work for BJP candidates. It did not see the government as its own.

Ghosh stayed away from the election work as Sudarshan had sent him to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in 2003. He worked there for four years, along with the Ramakrishna Mission, and was head of the RSS rescue operations in the wake of the 2004 tsunami. He also kept an eye on the foreign NGOs operating on the islands. Impressed with his work, some BJP leaders wanted him in the party. Sudarshan, however, declined. Ghosh himself was happy serving the RSS.

He soon became the eastern India chief of the Hindu Jagran Manch, an RSS affiliate that opposes conversion of Hindus to other religions and organises re-conversions. He remained in the role till 2015, when he was deputed to the BJP as general secretary (organisation). Within months, he was elevated as president of the party in West Bengal. The BJP had decided to capitalise on the decimation of the CPI(M) and the Congress in the state.

Today, the BJP has the total support of the RSS and its affiliates such as the Bajrang Dal, the Visva Hindu Parishad and the Hindu Jagran Manch. Though the BJP has not declared that Ghosh is going to be its chief minister, the RSS thinks that projecting him as the party’s man for the post would polarise the voters in the BJP’s favour. A state vice president of the party said Mamata had already polarised the Muslim vote.

Ghosh has gone deep into Muslim-dominated areas of South 24 Parganas district and held rallies there. This is known as the Trinamool’s bastion. In one rally, he warned Trinamool leaders in Diamond Harbour not to stop BJP supporters from voting; some voters were allegedly prevented in the last Lok Sabha election. “Just try doing that again. I would like to see which god would save you,” he bellowed, as the people broke into chants of ‘Jai Shri Ram’.

Trinamool leaders, like Diamond Harbour MP Abhishek Banerjee, have called Ghosh a goonda (thug). “Yes, I admit that I am a goonda because, otherwise, I would not tackle thieves and dacoits,” said Ghosh. Trinamool’s national spokesman and MP, Saugata Roy, described him as “uncultured”. Subrata Mukherjee, a senior cabinet minister, said, “His politics of violence has no place in Bengal. He has only learned how to hit or stone someone who is politically opposed to him.” A central committee member of the CPI(M), Sujan Chakraborty, said Ghosh was a “nonsense politician”.

Ghosh’s reply to Roy was polite. “I would learn culture when we form the government,” he said. “Till then, I cannot smile at my political opponents who have killed 130 of my party workers.”

If elected, he would be the first Bengali chief minister fluent in Hindi and the first one who was not educated in Kolkata. He once said he had a diploma from a polytechnic college, but the college denied having any record of him studying there.

In Parliament, he has been active in several committees, and in the Parliament library and canteen, he often seeks out senior MPs of the Congress and socialist parties to discuss politics and governance. Said Rajya Sabha member Pradip Bhattacharya of the Congress: “I do not subscribe to what Dilip says. It is utter rubbish. But I can say one positive thing about him. He has a backbone, which many leaders in Bengal lack.”

Ghosh has been allotted a sprawling bungalow in Delhi’s North Avenue, but he does not stay there when in the capital. Instead, he bunks with his friends at the party office. “I do not like the life in Lutyens Delhi. I do my job and come back to Bengal immediately,” he said.

On one of his trips to Delhi, he took his mother along, on her first pilgrimage to Mathura and Vrindavan. He visits his village in Bengal once a year. His father is no more and he has brought the rest of his family into the RSS.

In Kolkata, Ghosh lives in a large apartment under Z category security cover. Any visitor at his New Town residence has to go through many levels of security clearance. The apartment has guest rooms for his friends and a big hall and adjoining rooms for his security personnel from the Central Armed Police Forces.

Why did he not try to fit in with the bhadralok of Kolkata? Even Mamata Banerjee, who was impetuous and reckless while fighting the communists, softened a bit just before becoming chief minister. Her new slogan was: Badla noy, bodol chai (change, not revenge).

Why did Ghosh not address the bhadralok? As I repeated the question, he smiled and picked up the empty paper cups in which we had been served tea, and put them in a dustbin. For a leader hailing from the remote Junglemahal area, this was quite the gesture.